Late last year, Congress passed a joint resolution along these lines: “Whereas the United States has conferred honorary citizenship on 7 other occasions during its history, and honorary citizenship is and should remain an extraordinary honor not lightly conferred nor frequently granted;

[In case you’re wondering, I’ll save you a trip to Wiki. The others are Winston Churchill, Raoul Wallenberg, William and Hannah Penn, Mother Teresa, Casimir Pulaski and Lafayette.]

“Whereas Bernardo de Gaalvez y Madrid, Viscount of Galveston and Count of Gaalvez, was a hero of the Revolutionary War who risked his life for the freedom of the United States people and provided supplies, intelligence, and strong military support to the war effort…

“Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Bernardo de Gaalvez y Madrid, Viscount of Galveston and Count of Gaalvez, is proclaimed posthumously to be an honorary citizen of the United States.”

I didn’t know about that resolution until after Ann and I went to Galveston earlier this month, and I looked up Bernardo de Gaalvez y Madrid, Viceroy of New Spain, to add to my vague knowledge of the man for whom Galveston is named.

To my way of thinking, the first place to go in Galveston (after lunch, if you happen to arrive at lunchtime), is the Bishop’s Palace. That’s just what we did.

The name is a spot of Texas hyperbole. Palace, it isn’t. But it is a excellent example of a large (19,000 SF) Victorian mansion, built in the 1890s for a successful attorney and his wife, Walter and Josephine Gresham, who tapped local architect Nicholas J. Clayton to design it. (Clayton seems to have been very busy in the pre-1900 heyday of Galveston, but things were never the same after that.)

The name is a spot of Texas hyperbole. Palace, it isn’t. But it is a excellent example of a large (19,000 SF) Victorian mansion, built in the 1890s for a successful attorney and his wife, Walter and Josephine Gresham, who tapped local architect Nicholas J. Clayton to design it. (Clayton seems to have been very busy in the pre-1900 heyday of Galveston, but things were never the same after that.)

The Handbook of Texas Online describes Clayton’s work as “exuberant in shape, color, texture, and detail. He excelled at decorative brick and iron work… What made Clayton’s architecture so distinctive in late nineteenth-century Texas was the underlying compositional and proportional order with which he structured the display of picturesque shapes and rich ornament.”

The Handbook of Texas Online describes Clayton’s work as “exuberant in shape, color, texture, and detail. He excelled at decorative brick and iron work… What made Clayton’s architecture so distinctive in late nineteenth-century Texas was the underlying compositional and proportional order with which he structured the display of picturesque shapes and rich ornament.”

That’s a fitting description for the Bishop’s Palace, which was a sturdy mansion too. It survived the Hurricane of 1900, one of the few structures in the area to do so, and sheltered a lot of survivors. The bishop in the name is Bishop Christopher E. Byrne, who lived there in 20th century, after the Roman Catholic Diocese of Galveston bought the mansion in 1923. Only in 2013 did the Church sell the structure to the Galveston Historical Foundation.

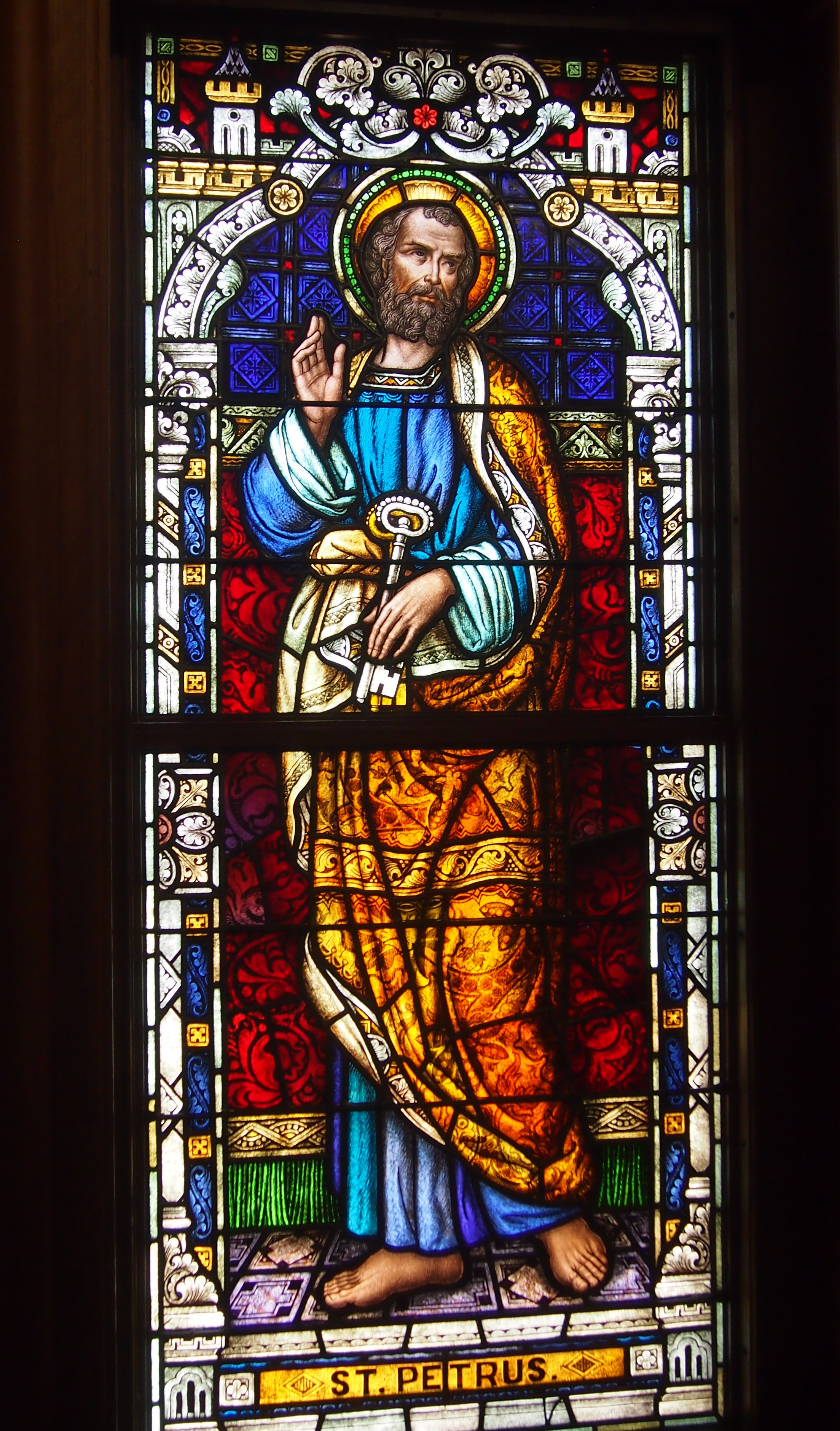

The interior has more stained glass than most Victorian mansions I’ve seen. Many of those were added by the bishop, who insisted that one of the rooms be converted into a chapel, which it remains. For instance, a stained-glass St. Peter’s there to greet you.

As usual, a house like this has some interesting period detail, such as the fact that the lights were built for gas as well as for that new light source, electricity, in case it worked out. Or the bathtub in the main second-floor bathroom.

As usual, a house like this has some interesting period detail, such as the fact that the lights were built for gas as well as for that new light source, electricity, in case it worked out. Or the bathtub in the main second-floor bathroom.

Note the three faucets. Our guide, an informative woman whose main job is teaching Texas History — everyone in the state takes it in 7th grade, or at least used to — told us that one was for hot water, one for cold, and one for rainwater from a cistern. It was thought to be good for one’s hair.

Note the three faucets. Our guide, an informative woman whose main job is teaching Texas History — everyone in the state takes it in 7th grade, or at least used to — told us that one was for hot water, one for cold, and one for rainwater from a cistern. It was thought to be good for one’s hair.

The Greshams had the means to be international travelers in the days before Europe on $5 a Day, and that meant steamer trunks. I don’t think I’d ever seen trunks of the time plastered with luggage labels, but Bishop’s Palace had some on display.

Next door to the Bishop’s Palace is Sacred Heart Catholic Church. This building dates from the early 1900s, because the 1900 hurricane knocked down the original.

Next door to the Bishop’s Palace is Sacred Heart Catholic Church. This building dates from the early 1900s, because the 1900 hurricane knocked down the original.

The church wasn’t open for a look inside. But the next-door location must have been convenient for the bishop. You know, in case he ever needed to tune up his crosier or something.

The church wasn’t open for a look inside. But the next-door location must have been convenient for the bishop. You know, in case he ever needed to tune up his crosier or something.