Libbey Inc.’s web site asserts that “the Libbey® brand name is one of the most recognized brand names in consumer housewares in the United States and among the leading brand names in glass tableware. Our products are sold in major retail channels of distribution in the United States and Canada, including mass merchants, department stores and specialty housewares stores.”

Maybe so. But I didn’t know about the Toledo-based glass giant until recently. Corning, I knew. But somehow not Libbey. So I wasn’t sure about the references I saw on Saturday to Libbey and the Libbey Foundation at the Toledo Museum of Art. Having no hand-held Internet access, I couldn’t check (and on the whole, that’s just as well). I guessed that maybe it had something to do with canned food.

Wrong company, wrong spelling, and in fact, Libby’s just a brand, not a company any more. The glass company notes: “Libbey has its roots in East Cambridge, Massachusetts, home of the New England Glass Company which was founded in 1818. William L. Libbey took over the company in 1878 and renamed it the New England Glass Works, Wm. L. Libbey & Sons Props. In 1888, facing growing competition, Edward Drummond Libbey moved the company to Toledo, Ohio. The Northwest Ohio area offered abundant natural gas resources and access to large deposits of high-quality sand. Toledo also had a network of railroad and steamship lines, making it an ideal location for the company. In 1892, the name was changed to The Libbey Glass Company.”

Why is this important to the Toledo Museum of Art? Let the museum take it from here: “1901 — Edward Drummond Libbey, founder, is elected first president of the board of trustees of the newly founded Toledo Museum of Art. The Museum begins humbly with 120 charter members, temporary exhibitions in rented rooms in the Gardner Building in downtown Toledo, and no permanent art collection.”

By gar, if New York and Chicago and Pittsburgh and Cleveland could have first-rate art museums, so could Toledo. Libbey not only founded the museum, he lived long enough to donate a lot more money to it and set it on a course of expansion, including $1 million in his will in the 1920s, back when that meant fat Coolidge dollars. In our time, the museum holds about 30,000 items and has 35 galleries. It would easily be at home in a larger city.

Only this part looks like a museum of 100 years ago, with its Ionic columns and such (and in fact it was designed by Edward B. Green and Harry W. Wachter in 1912). Other structures forming the museum include newer designs by Frank Gehry — but without his trademark curls — and the postmodern Glass Pavilion by the Tokyo architects Sejima and Nishizawa and Associates.

Only this part looks like a museum of 100 years ago, with its Ionic columns and such (and in fact it was designed by Edward B. Green and Harry W. Wachter in 1912). Other structures forming the museum include newer designs by Frank Gehry — but without his trademark curls — and the postmodern Glass Pavilion by the Tokyo architects Sejima and Nishizawa and Associates.

All together, it’s the kind of museum that can’t reasonably be seen in one go. So we looked at things until we felt like we weren’t seeing them any more (ah, here’s another room with paintings on the wall…) To begin with, we took in a good bit of the more recent works. I recognized this artist right away.

“Beuys Voice” (1990) by Nam June Paik, which a sign told us is new to the museum. I saw a larger, but distinctly similar work of his, in Arkansas last year. I like the hat.

“Beuys Voice” (1990) by Nam June Paik, which a sign told us is new to the museum. I saw a larger, but distinctly similar work of his, in Arkansas last year. I like the hat.

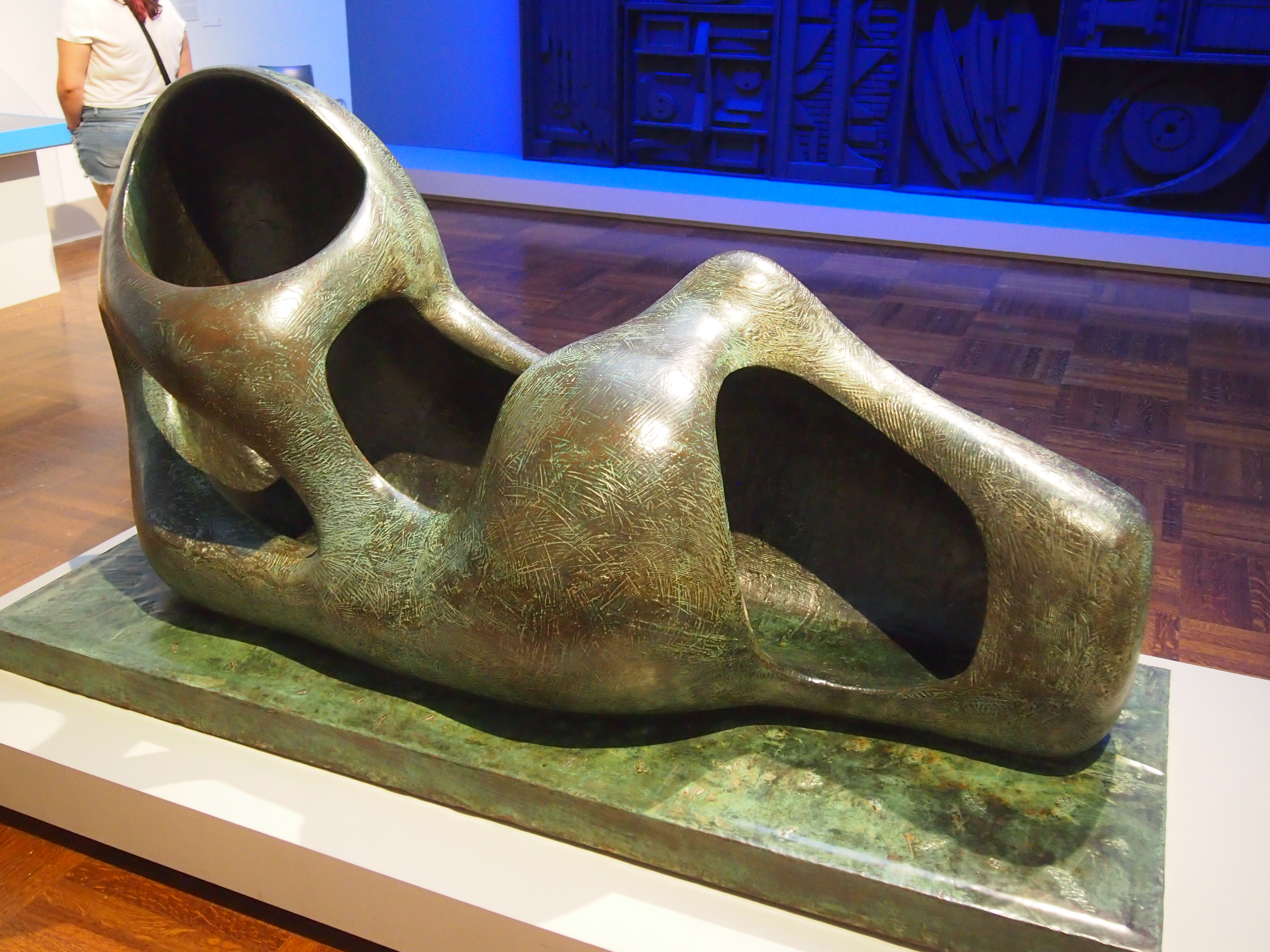

And of course it’s good to have a Henry Moore or two lying around (“Reclining Figure,” 1953-54).

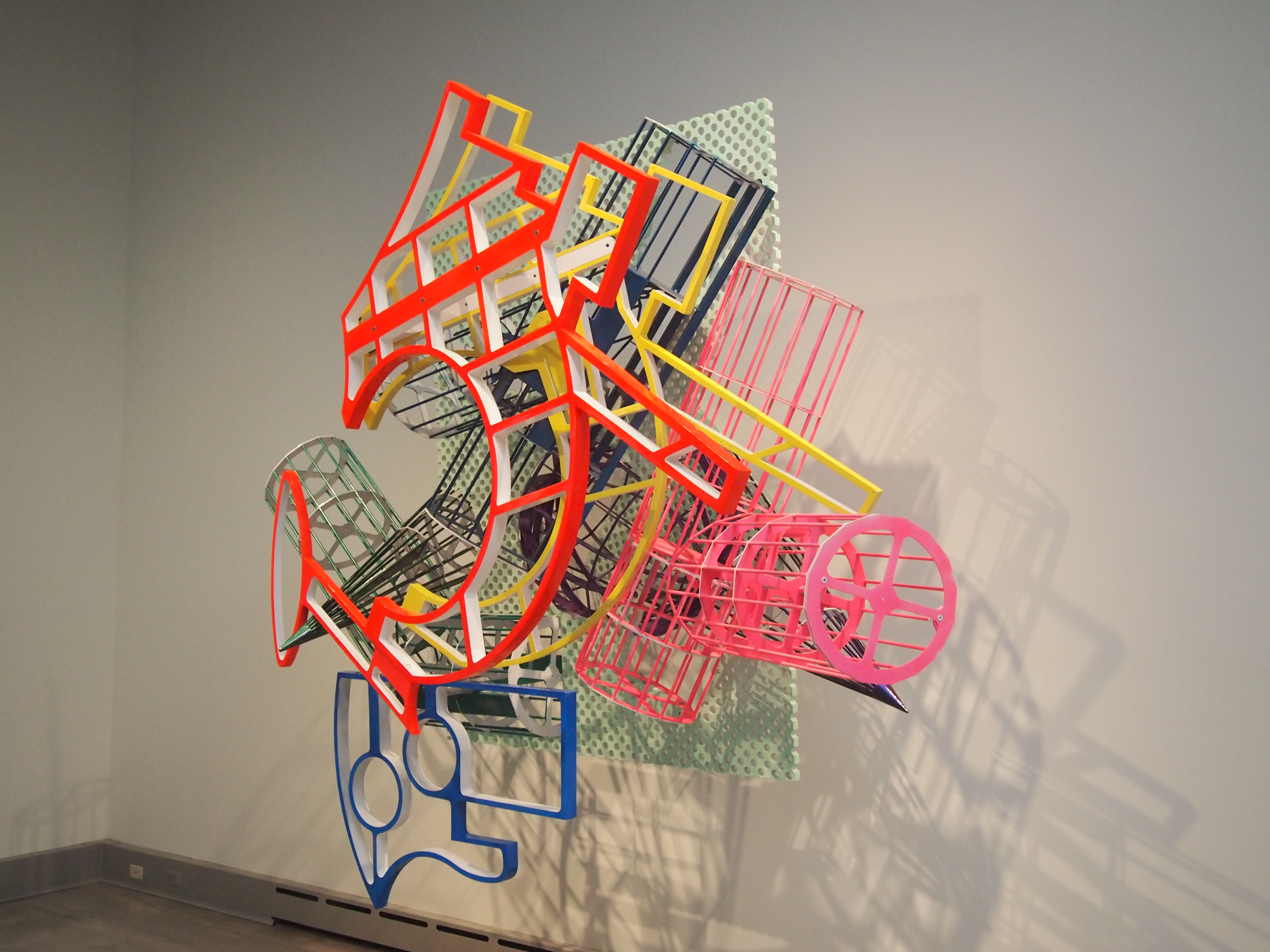

And a Frank Stella hanging around (“La Penna di hu,” finished in 2009).

And a Frank Stella hanging around (“La Penna di hu,” finished in 2009).

I rarely see artwork by Beninese artists. Never, that I can think of. This piece, “Made in Porto-Novo (MIP),” is by a fellow named Romuald Hazoume. It’s made of found objects — pieces of metal, mostly, stapled together — with sound coming from within.

I rarely see artwork by Beninese artists. Never, that I can think of. This piece, “Made in Porto-Novo (MIP),” is by a fellow named Romuald Hazoume. It’s made of found objects — pieces of metal, mostly, stapled together — with sound coming from within.

We also spent time among paintings of recent and earlier centuries. These do not photograph so well at the hands of an amateur like me, but I did do some details. Such as the face from “Portait of a Freedom Fighter” (1984), Julian Schnabel.

We also spent time among paintings of recent and earlier centuries. These do not photograph so well at the hands of an amateur like me, but I did do some details. Such as the face from “Portait of a Freedom Fighter” (1984), Julian Schnabel.

“London Visitors” (1874), James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot.

“London Visitors” (1874), James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot.

We couldn’t leave with checking out the ancient art. Nice collection, including the likes of this second-century AD statue.

We couldn’t leave with checking out the ancient art. Nice collection, including the likes of this second-century AD statue.

And an 18th-century copy of “Laocoön and His Sons.”

And an 18th-century copy of “Laocoön and His Sons.”

I made full use of the opportunity to tell Lilly the story of Laocoön calling out the Trojan Horse as, well, a Trojan Horse, throwing the spear, and being offed for his temerity by sea serpents, a circumstance that the Trojans fatally misinterpreted.

I made full use of the opportunity to tell Lilly the story of Laocoön calling out the Trojan Horse as, well, a Trojan Horse, throwing the spear, and being offed for his temerity by sea serpents, a circumstance that the Trojans fatally misinterpreted.

Even if there’s nothing else in Toledo worth seeing — and I know there is — the museum was definitely worth a few miles’ detour.