For once, I happened to be on the right side of the airplane when the pilot pointed something out. Namely, one of the massive forest fires burning on August 21 in the mountains of Washington state. It was an enormously tall, light gray cloud, reaching down toward the irregular ground below. If you looked carefully, you’d notice that very near the ground the cloud was tinged orange. I’d never seen the likes of it before.

Two days later, one of my ambitions on the road was to see Mount St. Helens, that storied volcano whose eruption captured the nation’s attention in the spring of 1980. No dice. When I got to the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument visitors center, the ranger there told me that while I could drive to the lookout points, visibility was nil because of forest fire smoke.

The only volcano I saw on this trip was on a sign not too far from the famed volcano.

I consulted my map and picked out something else in the vicinity to see. That turned out to be Mossyrock Dam in Lewis County, Wash.

I consulted my map and picked out something else in the vicinity to see. That turned out to be Mossyrock Dam in Lewis County, Wash.

Note the haze in the background. That was everywhere in the distance that day. Mossyrock Dam dates from toward the end of the U.S. dam-building frenzy of the 20th century, being completed in 1968 (the frenzy has moved to China in our time). It dams the Cowlitz River, a tributary of the Columbia, and its main purpose is hydroelectric production. According to a number of sources, Mossyrock is the tallest dam in Washington state. I’d have guessed the Grand Coulee Dam, but maybe it just gets better press.

Note the haze in the background. That was everywhere in the distance that day. Mossyrock Dam dates from toward the end of the U.S. dam-building frenzy of the 20th century, being completed in 1968 (the frenzy has moved to China in our time). It dams the Cowlitz River, a tributary of the Columbia, and its main purpose is hydroelectric production. According to a number of sources, Mossyrock is the tallest dam in Washington state. I’d have guessed the Grand Coulee Dam, but maybe it just gets better press.

While I was reading about the dam, I came across an article about some towns that were flooded by the creation of the lake. That’s interesting, but I was also reminded of hearing about the 1940s flooding of the town of Stribling, Tennessee. I’m pretty sure my cousin Cook Wilson of Mississippi told my brother Jay, and Jay told me. Or maybe Cook told both of us at the same time, but I would have been pretty young, eight or so.

I looked it up again, and Stribling is under Kentucky Lake, one of the Between the Rivers lakes created by the TVA. When I was a kid, I imagined that such a town included whole buildings covered with water, and if you dove down, you could open the doors and look inside flooded buildings. It didn’t occur to me that pretty much everything would have been carted away before the inundation, even if only for scrap, leaving only building foundations, if that. Which would soon be silted over.

I also saw some mossy trees near the Mossyrock Dam.

And a sign that might as well have said ABANDON ALL HOPE… What’s the point of this road?

And a sign that might as well have said ABANDON ALL HOPE… What’s the point of this road?

This is Riffe Lake, created by the Mossyrock Dam, and just as hazy that day.

This is Riffe Lake, created by the Mossyrock Dam, and just as hazy that day.

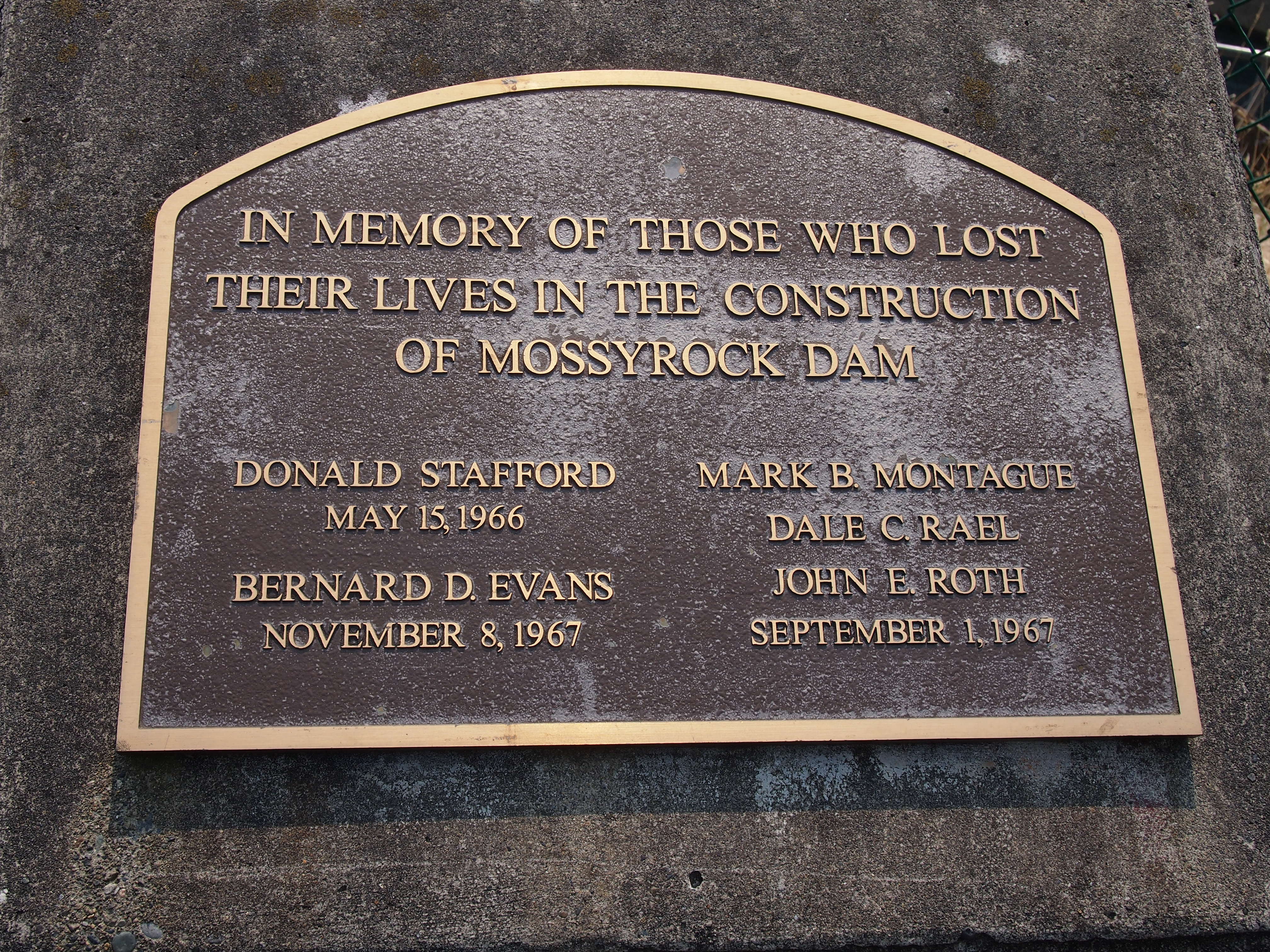

I noticed this plaque near the dam’s observation point. I’m glad the men have some kind of memorial. More than the many more who died building the Coulee seem to have gotten.

I noticed this plaque near the dam’s observation point. I’m glad the men have some kind of memorial. More than the many more who died building the Coulee seem to have gotten.

Something else I didn’t get to do: the Portland Aerial Tram. On the morning I got to Portland, I could see it, but without a more detailed map, I couldn’t get to the damned thing. The part of town that’s home to one of the terminals, which is on the river, is essentially cut off from the rest of town by a freeway, and if you don’t know the exact way to get past that obstacle, you’re out of luck. By the late afternoon, when I had a better map and could find the tram, it was closed. Ah, well.

Something else I didn’t get to do: the Portland Aerial Tram. On the morning I got to Portland, I could see it, but without a more detailed map, I couldn’t get to the damned thing. The part of town that’s home to one of the terminals, which is on the river, is essentially cut off from the rest of town by a freeway, and if you don’t know the exact way to get past that obstacle, you’re out of luck. By the late afternoon, when I had a better map and could find the tram, it was closed. Ah, well.

Portland has a number of light rail lines, and I rode those just to ride them. I also noticed these signs near the lines, something I’ve never seen anywhere else.

Portland has a number of light rail lines, and I rode those just to ride them. I also noticed these signs near the lines, something I’ve never seen anywhere else.

Up north, one thing I noticed about major Canadian surface streets — or at least those streets in the Vancouver area — was that there’s no such thing as a double yellow line. BC 99 turns from a limited-access highway into a six-lane major street as you enter the city, and it’s divided by a single yellow line. It’s silly how unnerving that was, because the difference is only a few inches. Even so, all that separates you from a mass of cars and trucks coming at you is a thin yellow line instead of a double thickness of two. Canadian drivers must be used to it.

Up north, one thing I noticed about major Canadian surface streets — or at least those streets in the Vancouver area — was that there’s no such thing as a double yellow line. BC 99 turns from a limited-access highway into a six-lane major street as you enter the city, and it’s divided by a single yellow line. It’s silly how unnerving that was, because the difference is only a few inches. Even so, all that separates you from a mass of cars and trucks coming at you is a thin yellow line instead of a double thickness of two. Canadian drivers must be used to it.

Know what else Vancouver doesn’t seem to have? Free parking. Not even at Stanley Park.

Finally, the Bullitt Center in Seattle, one of the greenest buildings in the nation, and a marvel of a building in that way.

For instance, that hat of a roof? An array of solar panels that produces more power than the building uses. As part of my work, I got a tour from the property manager. This is my writeup of the visit.

For instance, that hat of a roof? An array of solar panels that produces more power than the building uses. As part of my work, I got a tour from the property manager. This is my writeup of the visit.