Before we went, I was sure the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force would be packed with other visitors. After all, more than a million people visit every year, according to the Air Force; airplanes are popular. The museum is free. Or at least, no extra charge beyond taxation. And while Dayton isn’t the largest of places, it isn’t in the middle of nowhere either.

So I’ll bet attendance was high on Memorial Day weekend Saturday. But the place didn’t feel crowded, except maybe in the gift shop. The museum soaks up people like the best of sponges. Its current three buildings — enormous hangers — total about 750,000 square feet and house more than 360 aerospace vehicles and missiles.

The exhibits are organized chronologically, beginning with the first aeroplane that the Wrights sold to the U.S. Army, the Wright 1909 Flyer, and ending in a hall of ballistic missiles. Not all of the aircraft are American made or were even in the service of the United States. Among the early airplanes are those from all the nations that fielded warplanes in WWI, such as a Sopwith Camel, Nieuport 28, Curtiss Jenny, Caproni, and a Fokker Dr. I triplane, which the museum is careful to point out is associated with Rittmeister Manfred von Richthofen, though the one on display is a replica, since none survive.

I’d never seen most of those planes before. Or a Caquot observation balloon. The museum has the only one in existence. “The hydrogen-filled balloon could lift two passengers in its basket, along with charting and communications equipment, plus the weight of its mooring cable, to a height of about 4,000 feet in good weather,” notes the museum.

Hydrogen filled. The Western Front Association says of the balloons: “That the jobs of the balloon commander and observer were hazardous in the extreme is self-evident, and casualties were correspondingly high.” I believe it. The picture above doesn’t show the open gondola hanging from the balloon. The gondola of death, it was.

Hydrogen filled. The Western Front Association says of the balloons: “That the jobs of the balloon commander and observer were hazardous in the extreme is self-evident, and casualties were correspondingly high.” I believe it. The picture above doesn’t show the open gondola hanging from the balloon. The gondola of death, it was.

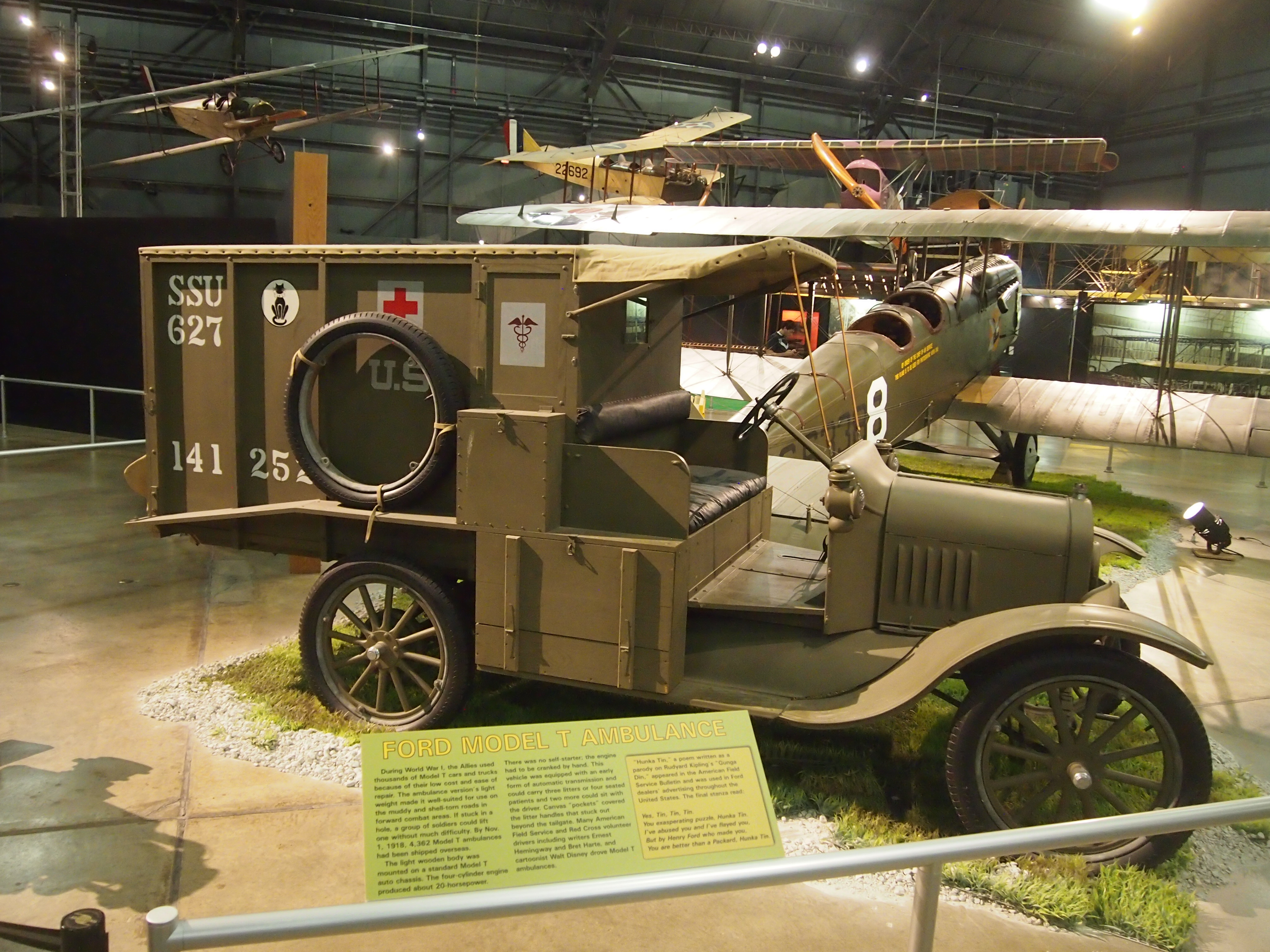

Not all of the artifacts are aircraft. Equipment associated with airplanes, and the wars they fought in, is also plentiful at the museum. One particularly amusing item in the early aircraft gallery was a Model T ambulance.

Not because ambulances are funny, but because of the “Gunga Din” parody about the vehicle, which is quoted on a sign near the artifact. The full poem is here.

Not because ambulances are funny, but because of the “Gunga Din” parody about the vehicle, which is quoted on a sign near the artifact. The full poem is here.

Yes, Tin, Tin, Tin!

You exasperating puzzle, Hunka Tin!

I’ve abused you and I’ve flayed you

But by Henry Ford who made you,

You are better than a Packard, Hunka Tin!

The difference between the WWI-era (and interwar) aircraft and WWII-era aircraft is astounding. That isn’t a revelation, but when you walk from one display to the other, the difference strikes you. The 1909 Flyer evolved into the likes of a B-29 Superfortress in only about 35 years. Think of the ingenuity.

The WWII gallery includes all kinds of interesting planes. Nothing like a modern war to spur the creation of weapons. Such as a Curtiss P-40, this one painted to represent one of the Flying Tigers that fought in China.

A B17-G, the Shoo Shoo Baby, which I understand will eventually be moved to the Smithsonian. The famed Memphis Belle, currently under restoration, will take its place as the museum’s prime B-17.

A B17-G, the Shoo Shoo Baby, which I understand will eventually be moved to the Smithsonian. The famed Memphis Belle, currently under restoration, will take its place as the museum’s prime B-17.

A B-24D Liberator, the Strawberry Bitch. The same kind of plane as Lady Be Good, which vanished in 1943 only to be found as wreckage in 1958 in the Libyan Desert.

A B-24D Liberator, the Strawberry Bitch. The same kind of plane as Lady Be Good, which vanished in 1943 only to be found as wreckage in 1958 in the Libyan Desert.

And of course, Bockscar. The Smithsonian got Enola Gay, the NMUSAF got Bockscar. Nearby were models of Little Boy and Fat Man, sitting beside each other. The nicknames were apt.

And of course, Bockscar. The Smithsonian got Enola Gay, the NMUSAF got Bockscar. Nearby were models of Little Boy and Fat Man, sitting beside each other. The nicknames were apt.

Those are only some of the larger WWII planes. Also on exhibit were plenty of others, such as more bombers and fighters, transports, trainers, and so on, including some enemy aircraft, notably a Zero and a Nazi jet fighter, built by Messerschmitt too late in the war to do the Germans much good. I’m pretty sure I saw a Zero at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, but the jet was a new one for me.

Those are only some of the larger WWII planes. Also on exhibit were plenty of others, such as more bombers and fighters, transports, trainers, and so on, including some enemy aircraft, notably a Zero and a Nazi jet fighter, built by Messerschmitt too late in the war to do the Germans much good. I’m pretty sure I saw a Zero at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, but the jet was a new one for me.

Ann was interested to learn about the artwork on the aircraft and the squadron patches. These were ways of individualizing something mass produced, I told her. Besides the Strawberry Bitch — which has a painting of a redheaded woman on one side — many of the other airplanes sported drawings for her to inspect. There was also a display case devoted to squadron patches, including many designed by the animators at Disney, who were doing their bit for the war effort, along with sending Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck et al. off in cartoons to flight the Axis.

Apparently the patches were quite popular among airmen. Then again, I suppose most of them had grown up during the heyday of Disney cartoon shorts. My own favorite patch shows Donald Duck hoisting a cartoon bomb, the round sort with a fuse that cartoon anarchists used to hoist.

The next hangers featured aircraft and other items from the Korean War, Vietnam, and the Cold War. We went through these a little more quickly than WWI or WWII, since the vastness of it all was beginning to wear us down. Even so, these galleries had a lot to recommend them, such as in the Korean collection: a vast Douglas C-124 cargo plane; a B-29 (“Command Decision”) that you can walk through; and a MiG.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a MiG, so famed in air-combat lore. A North Korean pilot took this one out on a mission and used it as a handy way to defect.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a MiG, so famed in air-combat lore. A North Korean pilot took this one out on a mission and used it as a handy way to defect.

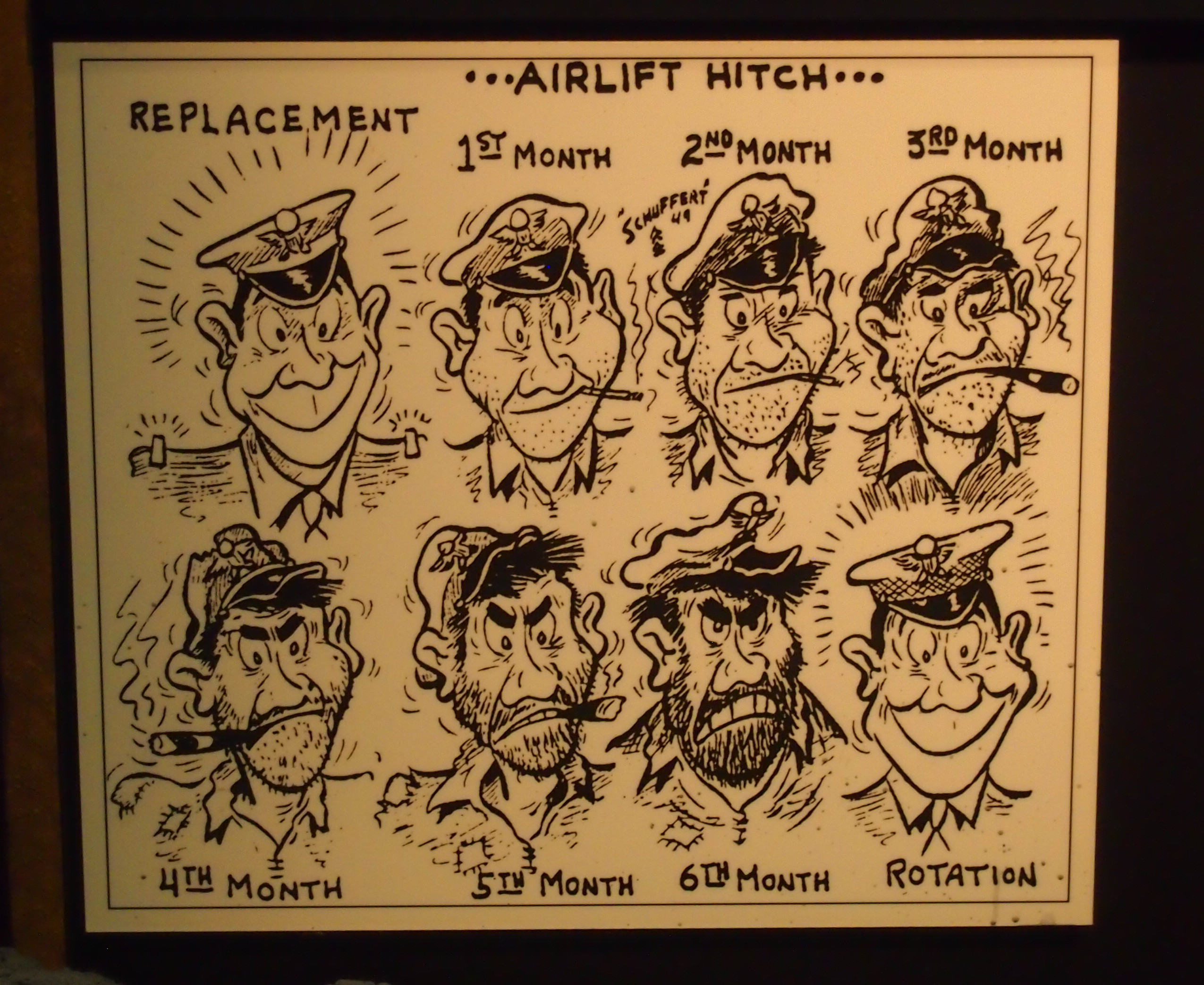

One hallway featured an exhibit about the Berlin Airlift. I was amused to see this.

It’s the work of TS Jake Schuffert, who did cartooning for the Airlift Times. I didn’t know the airlift had its own paper, but apparently so. Noted as niche cartoonist, he died in 1998.

It’s the work of TS Jake Schuffert, who did cartooning for the Airlift Times. I didn’t know the airlift had its own paper, but apparently so. Noted as niche cartoonist, he died in 1998.