It seems to be a misnomer, “Rivers of Steel,” at least as it applies to the Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark, yet that’s part of the official name. The Carrie Blast Furnaces produced pig iron, not steel. The facility, which is just outside Pittsburgh, then sent the iron across the Monongahela River to the vast steel works in Homestead, Pa., site of the 1892 battle between strikers and company goons (professional goons: Pinkertons).

So I’d call it Rivers of Iron. Or maybe Rivers of Molten Iron, which sounds more badass. But never mind, that’s just me picking the sort of nits that allow me to be a half-way decent editor.

We arrived at the Carrie Blast Furnaces in time for the 11 a.m. tour on July 6. The day was blazing hot. Fitting for visiting a place whose heat must have been hellish year-round when it was in operation.

The furnaces were originally built in 1881 and acquired by Andrew Carnegie in 1898, becoming part of U.S. Steel a few years later. They closed in 1978. These days, Allegheny County owns the site and a nonprofit manages it, including tours.

The abandoned pig iron foundry — actually two surviving furnaces along the river, #6 and #7, with the rest razed — is a hulking empire of rust and dust and bricks and voids. Enormous pipes rise into the sky. Twisted metal goes this way and that. Our guide’s constant reminder on pebble paths peppered with debris: watch your step. We watched our step, but when standing still, peered as much as possible into Pittsburgh’s, and America’s, industrial past.

Some soaring elements.

The king of the complex: one of the blast furnaces.

The king of the complex: one of the blast furnaces.

I listened to the explanations of what certain things were, and how the process moved along, but I don’t have a knack for metallurgy, so most of it didn’t stick. I did get the message about how dangerous and hard the work was, especially in the early days.

I listened to the explanations of what certain things were, and how the process moved along, but I don’t have a knack for metallurgy, so most of it didn’t stick. I did get the message about how dangerous and hard the work was, especially in the early days.

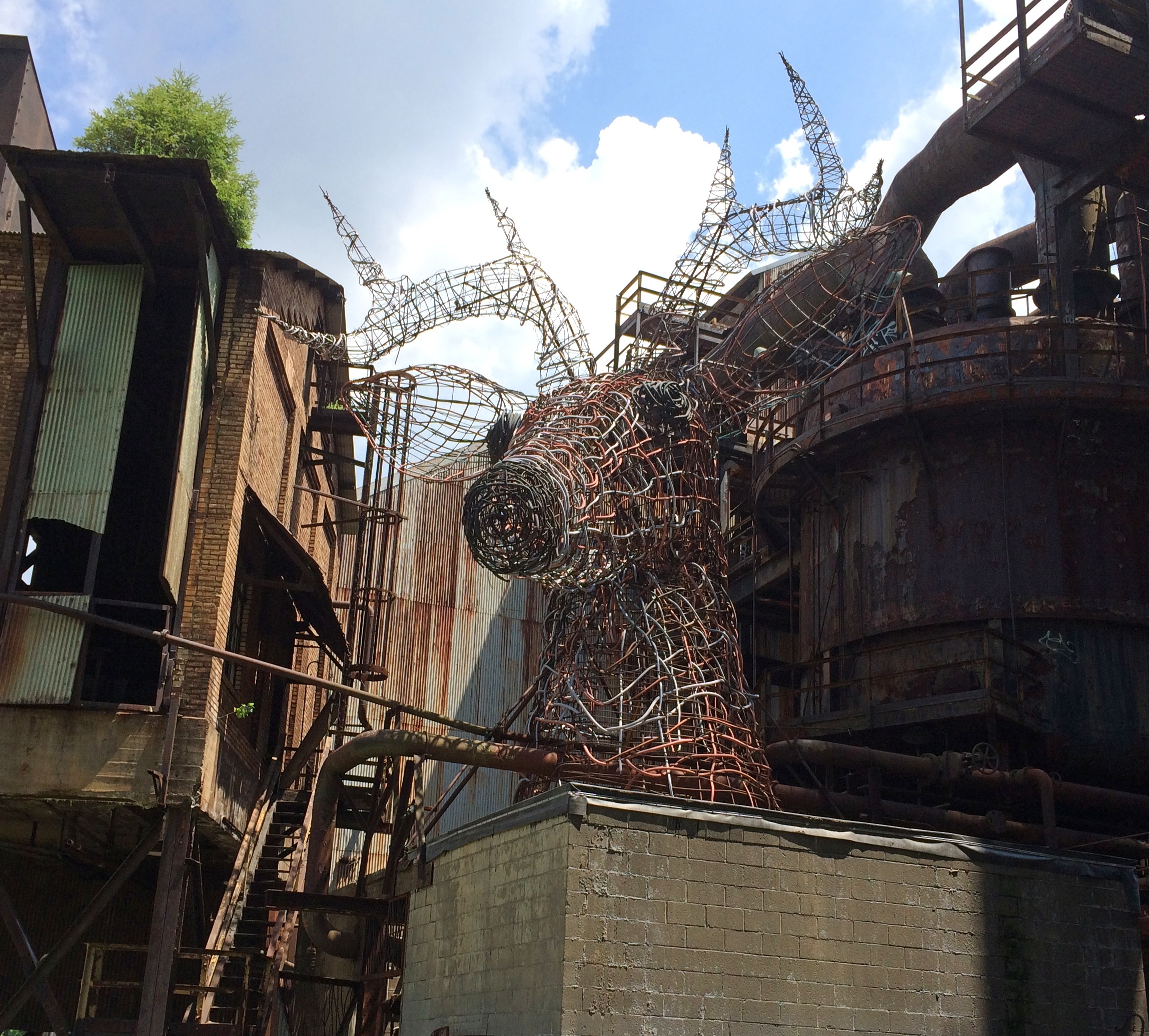

The site is also a nexus for graffiti and outsider art. The largest piece of outsider art was created some decades after the foundry was abandoned.

“In 1997, when the furnaces were in the hands of the privately owned Park Corp., a group of local artists entered the site, illegally, with the intention of constructing something from the materials that stayed when industry left: steel tubing, copper ties and wire from electrical conduit,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette says.

“Every Sunday for a year, the crew crawled through a hole in the fence, carrying their lunches and a few tools… The artists, whose seven head shots are posted on the exterior of the pump house, fastened the deer’s head on the ground and then lifted it atop the neck using a boat winch.”

Graffitists also roamed the site in its abandoned days. Inside a large shed (where the tour began), the walls are covered with it.

Elsewhere in the complex is a wall on which graffiti is now officially allowed.

“On this wall, it’s art,” the guide said. “Everywhere else, it’s vandalism.”