I didn’t realize it until later, but the National September 11 Memorial Museum, which is mostly underneath the former site of the World Trade Center Towers, only opened in May of this year, as opposed to the memorial, which opened in 2011. You access the museum through timed tickets. I thought it was worth visiting, but I’ll also say this: $24 is too much for any museum, regardless of subject or newness. If I hadn’t been traveling alone, and had to spend nearly $100 just to get my family in, I wouldn’t have gone, though I might have sent my children, who aren’t old enough to remember that day.

I was in the 2:30 pm line on October 10. A lot of other people entered at the same time. From the daylight at ground level, it’s something like entering a cave by walking down a wide ramp. That seemed a little odd at first, but I came around to the idea later, when I noticed signs in various parts of the museum telling me where I stood in relation to the towers, both in vertical and horizontal terms, such as Where You Are Standing Now was in the SE Corner of the North Tower, Third Basement Level (I’m making that up to illustrate the point). There would also be a graphic illustration to help you understand your position. Somehow it seemed important to know that. The space created for the museum used to be the foundation level of those behemoths.

The exhibits cover the building of the towers, their few decades of existence, their destruction, rescue efforts, the excavation, and the rebuilding, among other things. There are tributes to the first responders and the other victims, and displays about the attack on the Pentagon, and Flight 93, and the 1993 attack on the towers (the six victims of that incident are memorialized here, too, as they are at the above-ground memorial).

Much of the material was familiar, but a lot wasn’t. I was interested to learn, for instance, about Radio Row, the nickname of the Manhattan commercial district bulldozed in the 1960s to make way for the World Trade Center redevelopment (local property owners fought the eminent domain taking but lost). Some of images were arresting. Someone, for instance, made a video of the towers early in the morning of September 11, 2001, just after sunrise from the look of it, and it plays on one of the museum walls. Late summer Lower Manhattan was just minding its own business that morning.

Like any good history museum, the National September 11 Memorial Museum sports artifacts. An entire wall is an artifact: the Slurry Wall, built originally to keep the Hudson River from leaking into the lower levels of the tower, and the focus of much concern after the attacks. Namely, would it hold, or would an inundation add to the woes? It held. Part of it forms one of the walls of the museum, rising a few stories.

There’s also a staircase remnant, the Vesey Street Stairs. A lot of people escaped using those stairs, which survived the collapse, but were damaged during the excavation. They were installed between another staircase and an escalator that lead down into the main exhibit floor.

There’s also a staircase remnant, the Vesey Street Stairs. A lot of people escaped using those stairs, which survived the collapse, but were damaged during the excavation. They were installed between another staircase and an escalator that lead down into the main exhibit floor.

Twisted girders speak of extreme violence. These are from above the 90th floor of the North Tower, near the area that absorbed the impact.

Twisted girders speak of extreme violence. These are from above the 90th floor of the North Tower, near the area that absorbed the impact.

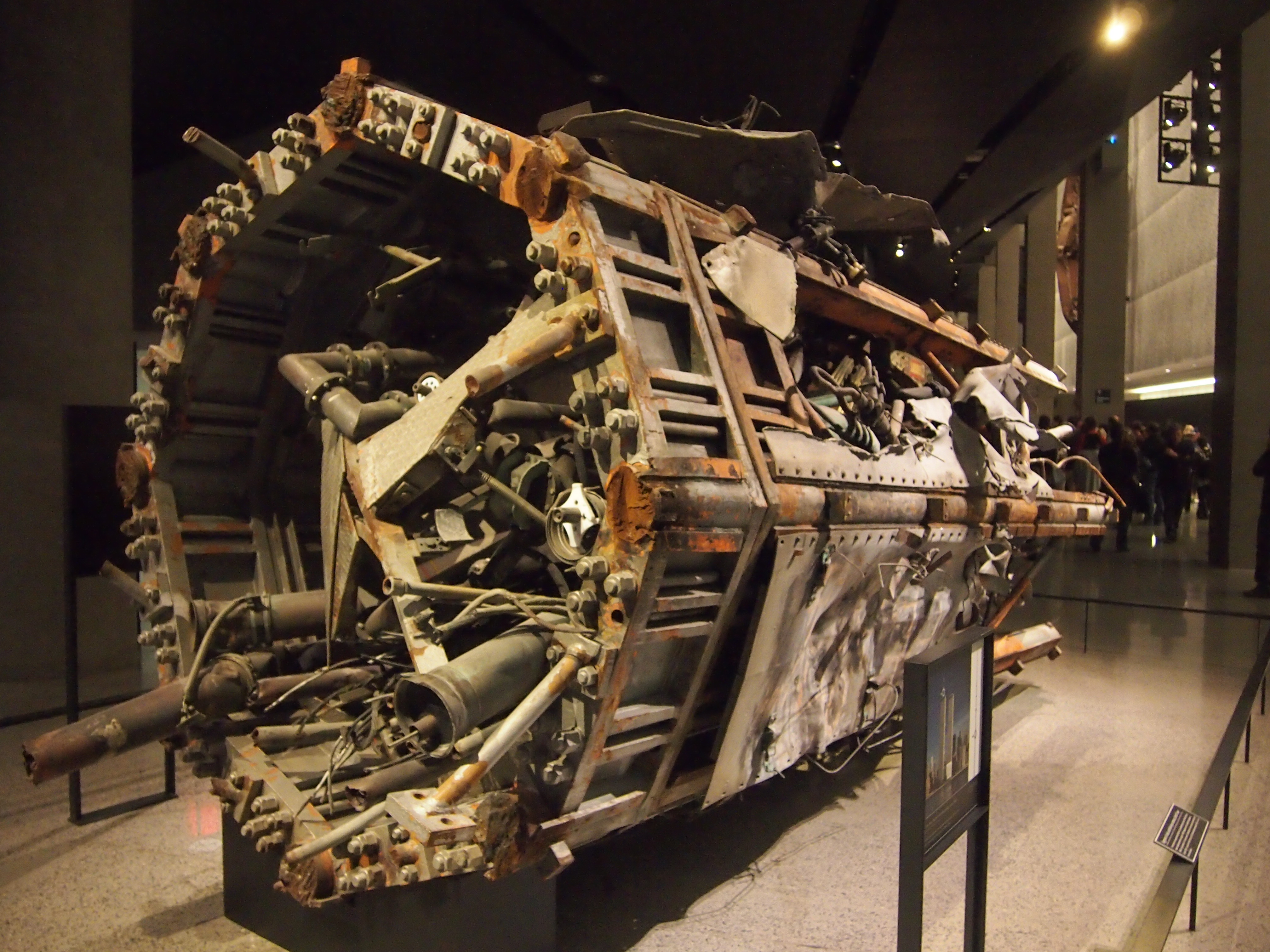

I wasn’t sure what this was until I read the sign. It was once a section of the antenna on the North Tower.

I wasn’t sure what this was until I read the sign. It was once a section of the antenna on the North Tower.

One of the fire engines destroyed by falling debris.

One of the fire engines destroyed by falling debris. This artifact wasn’t moved into location. It is what’s left of one of the box columns that used to support the buildings, so in a real sense the museum was built around it and the others like it. The North Tower had 84 of them, the South Tower 73.

This artifact wasn’t moved into location. It is what’s left of one of the box columns that used to support the buildings, so in a real sense the museum was built around it and the others like it. The North Tower had 84 of them, the South Tower 73.

The museum wasn’t just about the history of the event or the wreckage. An interior room (“In Memoriam”) had four walls covered with faces of the dead, arrayed in rows, with their names. Computer consoles allow you to look up a biographical sketch for any name on the wall. I looked up a few at random, and picked the most unusual name I found on the wall and made a note of it. I have a fondness for unusual names, after all.

The museum wasn’t just about the history of the event or the wreckage. An interior room (“In Memoriam”) had four walls covered with faces of the dead, arrayed in rows, with their names. Computer consoles allow you to look up a biographical sketch for any name on the wall. I looked up a few at random, and picked the most unusual name I found on the wall and made a note of it. I have a fondness for unusual names, after all.

I picked Ricknauth Jaggernauth. A fellow originally from Guyana, as it happened. The following is the entirety of his profile in the NYT in October 2001.

“Every day when he came home to Brooklyn from his construction job, Ricknauth Jaggernauth would grab a beer and sit in his front yard, and play with his grandchildren and other neighborhood children until it was time for dinner. ‘My father was a happy, loving, giving man,’ said his daughter Anita, 31. ‘He loved to talk to young people about their lives and about how important it was to get a good education.’

“He would have only one or two beers, but his wife, Joyce, teased him and called him ‘drunkie grandpa,’ a nickname the children used for him. He came here from Guyana 19 years ago, and worked for a company that was renovating offices in the World Trade Center. The day it was attacked, they were working on the 104th floor of the first tower.

“Mr. Jaggernauth, 58, planned to retire in two years and wanted to visit his homeland. He had five children and three grandchildren, and all lived together in the family’s two-story house on Pennsylvania Avenue. His daughter said that if his body is recovered, the family will have a traditional Hindu funeral for him. ‘It’s what he did for his own mother,’ she said.”