“Supermoon” again, eh? I took a look. I would have anyway, because I usually take out the trash on Sunday evenings, as I did yesterday. I understand that the Moon was at perigee, and closer than it will be for more than 20 years. So I looked up and there it was, looking like a nice full moon. That’s all.

Monthly Archives: November 2016

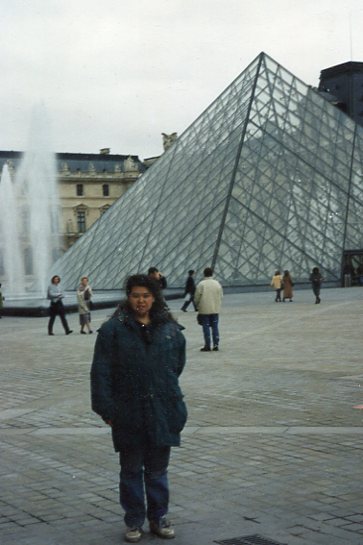

Paris 1994

November was a good time to be in Paris. So were the 1990s, as far as I could tell, though people sometimes pine for the Jazz Age or La Belle Époque in curious cases of nostalgia for times they never experienced. I take an interest in the history of places that I go, but I’m more interested in seeing them as they are now.

Which, after some time (say, 22 years), becomes places as they were then. Here I am on the Champs-Élysées.

I spent a few minutes with Google Maps trying to figure out exactly where I was, without conclusion. But I think Yuriko took the picture with her back to the Arc de Triomphe.

Here she is in front the Louvre Pyramid, which was fairly new at the time.

Even though it was November, the museum was ridiculously crowded. I’d hate to experience it in July.

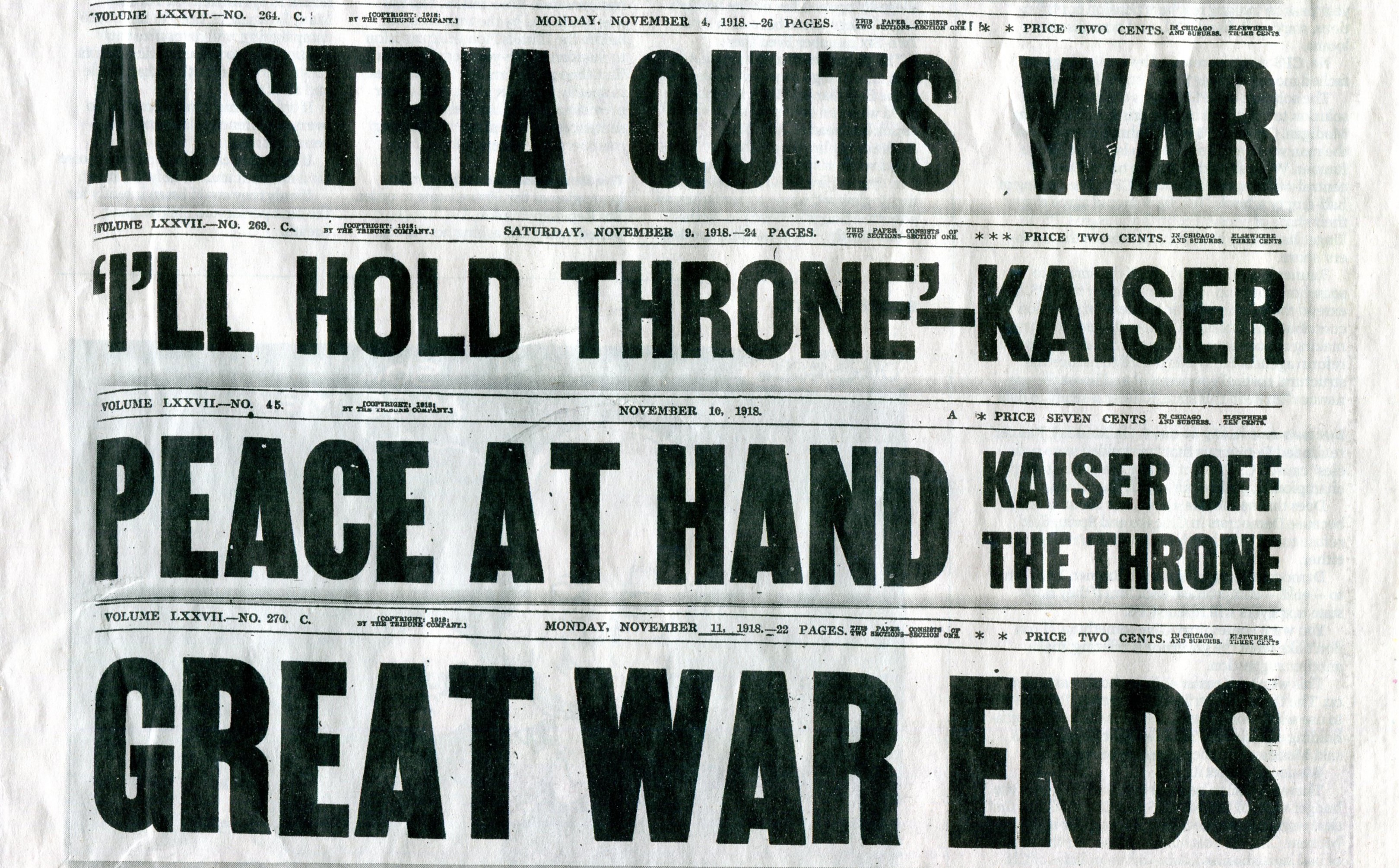

Armistice Day 2016

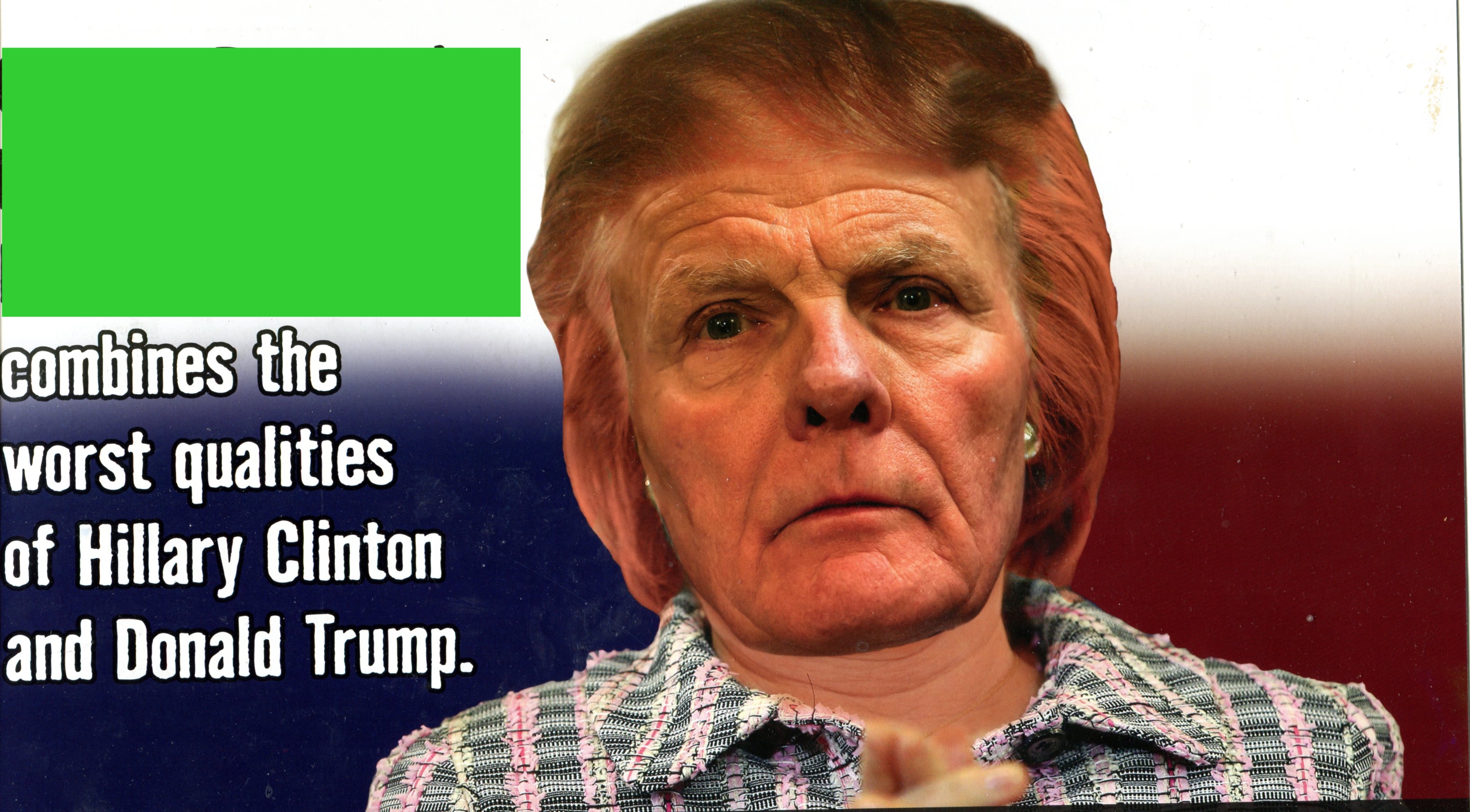

Photoshop Nightmare Election Leftover

Remarkably windy this afternoon, though not particularly cold. Yet winter is coming, as they say on a TV show I haven’t gotten around to seeing.

The influx — flow — torrent — of election season postcards has, of course, come to a sudden stop. I didn’t count the number that passed from campaigns, through to USPS, to our mailbox. And then into the recycle bin or, if I were in a less sustainable mood, the regular trash.

Most of them weren’t that memorable. Then there was this Photoshop nightmare.

It might not have changed my vote, but it did get my attention.

Otherwise, Today Was Fairly Normal

Not much to add to the volumes written about the election, and which will be, ad nauseam. Biggest surprise since 1948, maybe bigger than that. Trouble is, Trump is no Truman. No one knows what he’ll be in office. So it’s an awful gamble.

Best not to dwell on it too much at this juncture. Instead, hum something cheerful.

Presidential facts to mull over. Assuming President Obama finishes his term, and it’s a safe assumption, it will mark only the second time that three presidents in a row have held office for eight years each. The first time was long ago: Jefferson-Madison-Monroe. Four times in a row has never happened.

Also assuming Obama survives his term — and all of the other ex-presidents do, too — then there will be five living former presidents for a time after Jan. 20, 2017 (Carter, Bush, Clinton, Bush, Obama). That’s only happened three times: March 4, 1861-Jan 18, 1862; Jan. 20, 1993-April 22, 1994; and Jan. 20, 2001-June 5, 2004.

Donald Trump will be the first president from New York City since TR, though of course FDR was from New York state and so were a number of others. In fact, with the upcoming addition, that will make six presidents from New York state, same as Ohio, “Mother of Presidents.”

Phil-Tex Debris

I did my little part in the 58th quadrennial presidential election this morning — the 10th in which I’ve voted — at about 10:30, figuring that the morning rush would be over. Only one person was ahead of me when I arrived, but about a half-dozen were waiting when I left, so I guess there was ebb and flow throughout the day.

In Illinois, for the record, only four candidates were on the ballot for president: Democratic, Republican, Libertarian and Green. Left out: the Reform Party (remember them?); the Constitution Party, who seem to wuv the Constitution, except that pesky establishment clause; America’s Party, a splinter of the Constitution Party, because there are always splinters; the American Solidarity Party, an amalgam of social conservatism and economic redistributism; the Socialist Workers Party; the Communist Party USA; or any number of independents or micro-parties.

Besides Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, I managed to see three other burial grounds during my recent trip, two others in Philly, one in Lampasas, Texas, none of them by design. They all happened to be near places I was going anyway.

Across the street from the U.S. Mint is Christ Church Burial Ground, home to about 1,400 markers on two acres, many dating from Colonial or Revolutionary times. With its irregular stones, worn inscriptions and modern buildings just outside the walls, the place reminded me of King’s Chapel and the Granary Burial Ground in downtown Boston.

Christ Church’s most famed permanent resident is Benjamin Franklin, whose stone was covered with pennies. I overheard a guide say that the cemetery earns a couple of thousand dollars a year picking up the coins left for Dr. Franklin. I like to think he’d be amused by that. A penny saved might be a penny earned, but better for people to give you pennies because they want to.

Another resident I recognized was Benjamin Rush, patriot and man of medicine, in as much as that was possible at the time. His attitude toward bleeding was, alas, about the same as Theodoric of York. Still, he did what he could, especially during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793.

The burial ground is a few blocks away from Christ Church itself, which presumably needed the expansion space. The church has a smaller cemetery on its grounds, as well as burials inside. It’s a lovely, light-filled Wren sort of church.

Besides its importance as a place of worship for numerous leaders of the Revolution and early Republic, Christ Church was also pivotal in the organization of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. The Most Reverend William White, first presiding bishop of that church, is buried in the church’s chancel. (His house on Walnut St. is part of Independence National Historical Park these days.)

The churchyard is as much garden these days as cemetery.

Lampasas, Texas, is west of Killeen and Temple, and a burg of about 6,600. While driving along US 190 (Plum St.), a main road through town, I spotted Cook Cemetery, established as a pioneer graveyard in the mid-1850s, with its last known burial only in 1873.

Lampasas, Texas, is west of Killeen and Temple, and a burg of about 6,600. While driving along US 190 (Plum St.), a main road through town, I spotted Cook Cemetery, established as a pioneer graveyard in the mid-1850s, with its last known burial only in 1873.

In our time, it’s a slice of lightly wooded land between the road and a large parking lot. There are a number of stones, as well as broken stones and fragments, and a few burial sites enclosed by short walls.

A couple of stones include later markers denoting citizens of the Republic of Texas. For instance, this stone’s a little hard to decipher, but one of the dates seems to be November 8, 1855, or 161 years ago exactly. Could be the stone was erected that day, since Rebeca seems to have been born in 1801 and died in ’54.

A couple of stones include later markers denoting citizens of the Republic of Texas. For instance, this stone’s a little hard to decipher, but one of the dates seems to be November 8, 1855, or 161 years ago exactly. Could be the stone was erected that day, since Rebeca seems to have been born in 1801 and died in ’54.

Enough about cemeteries. Here’s something else I spotted in Philadelphia, at Market and 5th. Another Megabus.

Enough about cemeteries. Here’s something else I spotted in Philadelphia, at Market and 5th. Another Megabus.

In Dallas, I finally got a decent image of my brother Jay’s dogs, in one of their common poses.

In Dallas, I finally got a decent image of my brother Jay’s dogs, in one of their common poses.

Three More Philly Sites

One of the things to do while you wait to enter Independence Hall is take a look at the museum of the American Philosophical Society, which stands very near the hall itself.

I wasn’t aware that the APS is still an ongoing thing, but that’s just me being ignorant again. It’s a learned society, originally inspired by the old concept of leisure. “The first drudgery of settling new colonies is now pretty well over,” wrote Benjamin Franklin in 1743, “and there are many in every province in circumstances that set them at ease, and afford leisure to cultivate the finer arts, and improve the common stock of knowledge.”

I wasn’t aware that the APS is still an ongoing thing, but that’s just me being ignorant again. It’s a learned society, originally inspired by the old concept of leisure. “The first drudgery of settling new colonies is now pretty well over,” wrote Benjamin Franklin in 1743, “and there are many in every province in circumstances that set them at ease, and afford leisure to cultivate the finer arts, and improve the common stock of knowledge.”

The main current exhibit at the APS museum is Gathering Voices, which “tells the story of Jefferson’s effort to collect Native American languages and its legacy at the Society,” says the museum. “Jefferson had an abiding interest in Native American culture and language, while, at the same time, supporting national policies that ultimately threatened the survival of Indigenous peoples. As president of the APS from 1797 to 1814, Jefferson charged the Society with collecting vocabularies and artifacts from Native American nations. Over the next two hundred years, the APS would become a major repository for linguistic, ethnographic, and anthropological research on Native American cultures.”

It was an interesting display, including some documents in Jefferson’s hand. The collection isn’t as large as it might have been, however. The museum also tells this little-known story: “When Thomas Jefferson left Washington after two terms as President of the United States, he packed 50 Native American vocabulary lists in a trunk and sent them on a river barge back to Monticello along with the rest of his possessions. Somewhere along the journey, a thief stole the heavy trunk, thinking it was full of treasure. Upon discovering it was only filled with papers, he tossed the seemingly worthless contents into the James River. The loss of the vocabularies represented the destruction of 30 years of collecting on Jefferson’s part.”

Photocopying. That’s what Jefferson needed, but didn’t have.

In the West Wing of Independence Hall, there’s a small exhibit that doesn’t require waiting or a ticket to enter — another thing you can do while waiting to get into the rest of the hall. The exhibit is called Great Essentials.

On display are original printed copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. All very interesting, but the thing that really got my attention was the Syng inkstand. A fine work of silversmithing, and highly placed in the history of the United States. It may be the only inkstand anywhere that has a proper name, though I wouldn’t swear to it.

“Irish-born Philip Syng was the son of Philip Syng, a silversmith,” notes the Penn University Archives and Records Center. “In 1714 he and his father emigrated to America. In 1726, after a successful apprenticeship in Philadelphia and a trip to England, Philip established himself as a silversmith in Philadelphia. In 1730 he married Elizabeth Warner; together they had at least eighteen children.

“Perhaps on his trip to England, and if not, soon thereafter, Syng met Benjamin Franklin. The two formed a friendship, leading to Syng’s inclusion in the Junto, Franklin’s group of political and intellectual civic leaders… Syng was also elected to various public offices including city assessor, warden of the port, and treasurer of the city and county of Philadelphia.

“Syng was renowned as a silversmith, creating the finest work for Philadelphia’s leading families. His most famous work was the inkstand he made for the Pennsylvania Assembly, which was then used by the signers of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. He provided seals for the Library Company, the Union Fire Company, the Philadelphia Contributionship and for various surveyors and Pennsylvania counties. His shop produced not only silver bowls, tankards, teapots and trays but also gold belt buckles, buttons and teaspoons.”

A block north of Independence Hall is a visitors center of fairly recent vintage, at least compared with the original buildings, and across Market St. from the center — between it and the Liberty Bell — is the President’s House Site.

I quote the NPS on the history of the site at some length, because it’s a relatively unknown place, but much happened there. It was originally built in 1767, and was known as the Masters-Penn house (a grandson of William Penn lived there in its early days).

“In September 1777, British forces under General Sir William Howe occupy Philadelphia after the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown. General Howe makes the Masters-Penn house his winter residence and headquarters while Washington and his troops retreat to Valley Forge. In June 1778, the British evacuate Philadelphia and consolidate their forces in New York.

“Colonial forces enter Philadelphia under the command of Major-General Benedict Arnold. Arnold promptly makes the Masters-Penn House his residence and headquarters. In March 1779, Arnold resigns his post and two months later, while still living in the house, he begins his treasonous correspondence with the British.

“In January 1780, the house is severely damaged by fire, and is subsequently purchased and rebuilt by Robert Morris, the famed ‘Financier of the Revolution.’ Morris rebuilds the house to its original plan, enlarges the property, and adds an icehouse and several back buildings.

“In 1790, Robert Morris volunteers his house to serve as President Washington’s residence while Philadelphia temporarily serves as the nation’s capital. Washington occupies the property from November 1790 to March 1797, during which time his household includes nine enslaved Africans brought up from Mount Vernon. He also makes several enlargements and modifications to the house and back buildings, including the addition of a slave quarters between the kitchen and stables.

John Adams succeeds Washington as President and moves into the President’s House in March 1797. Adams leaves Philadelphia in 1800 and moves into the newly completed White House in Washington D.C. on November 1.”

So it’s a house associated with the Penn family, Gen. Howe, Benedict Arnold, Robert Morris, George Washington and John Adams. What happened to it later?

“In 1832, the building is demolished and rebuilt as a series of three narrow stores. Only the east and west walls of the original house are left standing, and are incorporated into the later commercial buildings… In 1935, the later commercial properties are themselves demolished, although remnants of the original east and west walls of the President’s House survive until the early 1950s. In 1951, the entire block is razed.”

What’s standing there now is a monument, completed in 2010 after much agitation, to the slaves who came with George Washington to attend his household while he lived there. (And whom he rotated back and forth to Virginia to avoid having to free them under Pennsylvania law.)

“Dominating the site as a whole is a large glass enclosure — the architects, Kelly/Maiello Architects & Planners, call it a ‘glass vitrine’ — protecting the fruits of a 2007 archaeological excavation. Within, about 10 feet below street level, visitors can see the remains of house foundations, revealing both the world of Washington and Adams (who held no slaves), and the world of indentured servants and Washington’s black chattel.”

For the record, Moll, Christopher Sheels, Hercules, his son Richmond, Oney Judge, her brother Austin, Giles, Paris, and Joe were the slaves who worked for President Washington at the Philadelphia household.

Of Hercules, the president’s chef, Wiki notes that “Stephen Decatur Jr.’s book Private Affairs of George Washington (1933) stated that Hercules escaped to freedom from Philadelphia in March 1797, at the end of Washington’s presidency… In November 2009, Mary V. Thompson, research specialist at Mount Vernon, discovered that Hercules’s escape to freedom was from Mount Vernon, and that it occurred on February 22, 1797 – Washington’s 65th birthday…

“At Martha Washington’s request, the three executors of Washington’s Estate freed her late husband’s slaves on January 1, 1801. It is possible that Hercules did not know he had been manumitted, and legally was no longer a fugitive.

“In a December 15, 1801 letter, Martha Washington indicated that she had learned that Hercules, by then legally free, was living in New York City. Nothing more is known of his whereabouts or life in freedom.”

The Second Bank of the United States & The Faces Within

Unusually warm these last few days. Today was so pleasant I cooked brats outside and we ate them outside for lunch. More leaves are gone than not, so for the moment there’s a mismatch between temperature and foliage, for this part of the country. It’s certain not to last.

The Second Bank of the United States is at 420 Chestnut St. in Philadelphia, just two blocks from Independence Hall. The gallery was as sparsely visited on October 22, a Saturday, as Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell were overrun by visitors. It’s the bank that President Jackson famously slew with a veto of its re-chartering in the summer of 1832, an act that was the focus of the election that fall — which Jackson won resoundingly.

The building is a handsome, bank-as-Greek temple sort of structure designed by William Strickland. Him again. I hadn’t realized he was so prominent in Philadelphia, since I’ve long associated him with Nashville. These days, the building is known as the Portrait Gallery in the Second Bank of the United States, displaying many portraits of Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary luminaries.

That includes a large collection of paintings by Charles Willson Peale, whom I didn’t appreciate until looking at one portrait of his after another. The man had some serious talent for portraiture, and much else besides.

I spent time especially with lesser-known figures of the period, though I didn’t see Button Gwinnett. The nation may have just heard of that Declaration signer from Georgia, but I did a report on him in the 8th grade, when we had to do reports on signers (picked at random, I think). I remember him, because his name is hard to forget.

All of the portrait examples from the Second Bank of the United States posted here were painted by Peale. The Founding Fathers are always worthwhile to ponder, but a lot of other interesting people characterized the period. David Rittenhouse, for instance.

Talk about a lesser-known man of the Enlightenment. Of special interest to me is that he was a skilled astronomer — one of those worldwide who observed the Transit of Venus in 1769 — and first director of the U.S. Mint. Not only that, he built swell orreries and surveyed borders for mid-Atlantic states, including the half-circle border between Pennsylvania and Delaware.

“His scientific thinking and experimentation earned Rittenhouse considerable intellectual prestige in America and in Europe,” says the Penn University Archives & Records Center. “He built his own observatory at his father’s farm in Norriton, outside of Philadelphia. Rittenhouse maintained detailed records of his observations and published a number of important works on astronomy, including a paper putting forth his solution for locating the place of a planet in its orbit.

“He was a leader in the scientific community’s observance of the transit of Venus in 1769, which won him broad acclaim. He also sought to solve mathematical problems, publishing his first mathematical paper in 1792, an effort to determine the period of a pendulum. He also experimented with magnetism and electricity.”

Here’s John Dickinson, who didn’t support the Declaration. Later, though, he did his part for independence, and was a delegate in 1787.

“On July 1, 1776, as his colleagues in the Continental Congress prepared to declare independence from Britain, Dickinson offered a resounding dissent,” says HistoryNet.

“Deathly pale and thin as a rail, the celebrated Pennsylvania Farmer chided his fellow delegates for daring to ‘brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.’ He argued that France and Spain might be tempted to attack rather than support an independent American nation.

“He also noted that many differences among the colonies had yet to be resolved and could lead to civil war. When Congress adopted a nearly unanimous resolution the next day to sever ties with Britain, Dickinson abstained from the vote, knowing full well that he had delivered ‘the finishing Blow to my once too great, and my Integrity considered, now too diminish’d Popularity.’ ”

Here’s a nice dramatization of that moment from John Adams, with Dickinson portrayed by Zeljko Ivanek.

This is Thayendanegea, also known as Joseph Brant, a Mohawk war chief who was decidedly not on the side of the colonists during the Revolution.

He was pro-British in the war, in that it served the interests of the Iroquois Confederation. Awfully even-handed of the gallery to include him, though it’s good to acknowledge his leadership skills, which apparently were many in war and diplomacy.

“The Mohawks chose to support the British because American colonists were already overrunning their lands,” says Upper Canada History. “The alliance was not unnatural as far as the Natives were concerned. For more than a hundred years, the Iroquois League had allied itself with the British in their long conflict with the Algonquins. Brant, Mohawk chief, had fought alongside the British in the Seven Years’ War and he remained loyal to the redcoats. This new alliance was really just a continuance of their long-standing cooperation…

“Brant fought with fierce determination against the Americans on the frontier and distinguished himself as one of their most courageous warriors and ablest strategists. His contribution to the cause did not go unrewarded. Of Brant’s loyalty and leadership, Lord Germain wrote, ‘The astounding activity of Joseph Brant’s enterprises and the important consequences with which they have attended give him a claim to every mark of our regard.’ In 1779 Brant received a commission signed by the king as ‘captain of the Northern Confederate Indians’ in appreciation of his ‘astonishing activity and success’ in the king’s service. Even though he esteemed his rank as captain, he preferred to fight as a war chief.”

After the Americans won the war, Thayendanegea led his people to Canada, with mixed results. He’s regarded highly enough in Canada to have been on a proof silver dollar in 2007, the bicentennial of his death.

Independence Hall

Just before midnight last night, I heard the distinctive popping of fireworks in the neighborhood.

I took that to mean that the Cubs won in far-off Cleveland. So they had. Not to be a mope, but I don’t know that the curse is actually broken. The curse could be, after all, that the Cubs will only win the World Series once a century. We may not ever find out; Neil and his generation might, though.

“Independence Hall,” said the guide at Independence Hall, “is the most important historic building in the entire country.” The guide, a gentlemen of retirement age and now a volunteer for the National Park Service, had probably been a teacher at one time. He had that manner, anyway.

He made a brief case for his assertion. “How can I say that? There are a lot of important historic buildings in every part of the country. But the key word is country. Because of what happened here, there’s a country that has a history.”

Not a bad argument. When you’re in a place like Independence Hall, where such weighty events occurred, such notions carry some weight. In as much as the United States was created in one place, this was it.

There’s nothing surprising about how the building looks. Everyone’s seen it depicted any number of times, including the Bicentennial Half Dollar (a nice design; the coin should have kept it) and the back of the current $100 Federal Reserve Note, which admittedly, I don’t see that much.

There’s nothing surprising about how the building looks. Everyone’s seen it depicted any number of times, including the Bicentennial Half Dollar (a nice design; the coin should have kept it) and the back of the current $100 Federal Reserve Note, which admittedly, I don’t see that much.

What surprised me was that Chestnut St., an ordinary street, runs right in front of the building. Maybe that’s too important a city street to close off, though I would have guessed that security-minded, or -obsessive, officials would want to. Apparently not.

The building was designed by Andrew Hamilton to house the Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and finished in 1753. Interestingly, in our time the building is actually owned by the City of Philadelphia — the Commonwealth having quit using it long ago — but administered by the National Park Service since 1948.

Another thing I learned about Independence Hall: William Strickland designed its distinctive clocktower, the same architect who did the fine Tennessee State Capitol. That was well after the meetings that ushered in the Declaration and the Constitution, however. The original steeple had rotted away as early as the 1780s, and was demolished in 1781. The Strickland replacement wasn’t until 1828, so when the delegates met to fix the Articles of Confederation in ’87, and came away with a new Constitution, that isn’t what they would have seen.

Independence Hall is only part of Independence Hall National Historic Site. Other structures include a modern Visitors Center, the Supreme Court Chamber in Old City Hall, Congress Hall, the First and Second Banks of the United States, Carpenters’ Hall, Merchants’ Exchange — another Strickland building — the Todd House, the Bishop White House, and of course the Liberty Bell Center.

There was a long line to get into to see the Liberty Bell (it too has been on a coin. More than one). I didn’t feel like waiting, especially since the bell is visible from a window, fairly close up. It has heft, that’s for sure. And yet it’s cracked. Maybe that’s a better symbol of fragile liberty than is generally acknowledged.

Getting into Independence Hall took a fair amount of time, first waiting to go through a metal detector, and then waiting for your timed tour of the inside. If you don’t order your tickets ahead of time, you risk not being able to get in.

Getting into Independence Hall took a fair amount of time, first waiting to go through a metal detector, and then waiting for your timed tour of the inside. If you don’t order your tickets ahead of time, you risk not being able to get in.

Upon entering Independence Hall, you first assemble in a room — the East Wing of the building — in which the guide tells you about the building, how to comport yourself, etc. Then you enter the room that used to be Pennsylvania Supreme Court chamber; here’s a better picture than I could take.

Upon entering Independence Hall, you first assemble in a room — the East Wing of the building — in which the guide tells you about the building, how to comport yourself, etc. Then you enter the room that used to be Pennsylvania Supreme Court chamber; here’s a better picture than I could take.

The current interior of the courtroom, as well as the Assembly Room famed for the Declaration and the Constitution, is a mid-20th century reconstruction by the National Park Service, with the public rooms restored to their 18th-century appearance. Between the late 18th century and the mid-20th, after all, the building was changed and modified, as buildings tend to be.

This is the Assembly Room.

“One the questions I’m always asked,” our pedagogic guide said, “is whether the furniture is original. The answer is no. Most of it isn’t. But if you think about, the furniture isn’t why you’ve come to see this room. You’re here because what happened here.”

Sure enough. But he did point out that the president’s chair on display on the dais is the one that George Washington sat in when he presided at the Constitutional Convention.

Upstairs is the Long Room, where events were, and are, held. It’s long, all right.

Our guide had more tidbit to offer when we were there. During Lafayette’s triumphal tour of the United States in 1824-25, when he was feted everywhere he went, a particularly lavish reception for was held for him in the Long Hall, which was part of the Pennsylvania State Hall at the time (he got a parade in Philly too). The building was called the “Hall of Independence” for the event, the first known reference using that terminology. That was an early step for the building toward becoming a National Historic Site and a World Heritage Site too.

Our guide had more tidbit to offer when we were there. During Lafayette’s triumphal tour of the United States in 1824-25, when he was feted everywhere he went, a particularly lavish reception for was held for him in the Long Hall, which was part of the Pennsylvania State Hall at the time (he got a parade in Philly too). The building was called the “Hall of Independence” for the event, the first known reference using that terminology. That was an early step for the building toward becoming a National Historic Site and a World Heritage Site too.

The U.S. Mint, Philadelphia

These days the headquarters of the U.S. Mint might be in Washington, DC, but its main branch is in Philadelphia, put there when that city was the national capital for a decade or so in the late 18th century. Congress created a national mint as part of the Coinage Act of 1792, as it was authorized to do by the Constitution (Article I, Section 8).

The 1792 law is an interesting read for numismaphiles, especially the specifications for U.S. coinage — and the fact that the direct ancestor of our dollar was the Spanish milled dollar “as the same is now current.” This fact ought to be better known.

“By far the leading specie coin circulating in America was the Spanish silver dollar, defined as consisting of 387 grains of pure silver,” notes Murray N. Rothbard in “Commodity Money in Colonial America.” (The libertarian economist who seemed to have no love for that invention of the Devil, fiat money; still, I’ll bet he’s reliable when taking about the nothing-but-metal currency of the early Republic.)

“The dollar was divided into ‘pieces of eight,’ or ‘bits,’ each consisting of one-eighth of a dollar,” Rothbard wrote. “Spanish dollars came into the North American colonies through lucrative trade with the West Indies. The Spanish silver dollar had been the world’s outstanding coin since the early 16th century, and was spread partially by dint of the vast silver output of the Spanish colonies in Latin America. More important, however, was that the Spanish dollar, from the 16th to the 19th century, was relatively the most stable and least debased coin in the Western world.”

Indeed, the Spanish dollar was legal tender in the U.S. until 1857. Then there’s Section 19 of the 1792 law, on the penalties for debasing coins: “If any of the gold or silver coins which shall be struck or coined at the said mint shall be debased or made worse as to the proportion of the fine gold or fine silver therein contained, or shall be of less weight or value than the same out to be pursuant to the directions of this act… every such officer or person who shall commit any or either of the said offenses, shall be deemed guilty of felony, and shall suffer death.”

Italics added. I’m not going look into it further right now, but maybe that penalty was inspired by the penalty for such misdeeds at the Royal Mint, which I suppose would be a direct offense against the sovereign. Also, I doubt that anyone ever was executed in the United States for such a crime, though a few mint miscreants have probably been tossed in the jug over the decades.

In any case, the expectation in 1792 seemed to be that the mint would move with the national capital, but things didn’t work out that way. According to the Mint, in 1801 — after Washington City had been established, though it wasn’t much more than a marshy place on the Potomac — “Congressional legislation directs the Mint to remain in Philadelphia until March 1803.

“Mint Officials were not in favor of relocating the facility to the newly established Federal City in Washington, and addressed their concerns many times. Legislation extending the Mint’s stay in Philadelphia appears throughout the early 1800s. Most extensions were for five years. At some point Congress seems to have tired of these extensions. An Act of May 19, 1828, leaves the facility in Philadelphia ‘until otherwise provided by law.’ ”

Since then, the United States has manufactured coinage in four locations successively in Philadelphia. The first and second sites no longer exist. The current mint facility, a large concrete building not too far north of Independence Mall, dates from the 1960s. It’s the fourth facility, designed by Philadelphia architect Vincent G. Kling and, while concrete, isn’t especially brutal. Or that good-looking either.

As you’d expect, the third facility, completed in 1901, has more style. The Beaux Arts building, I’m glad to report, still exists. It’s home to the Community College of Philadelphia these days. I didn’t have time to see it, so it counts as another reason to return to Philadelphia sometime.

You enter the modern mint building on N. 5th St., through an entrance that has a guard and a metal detector. No photography allowed inside. The first place you come to is a floor that includes the gift shop and an electronic sign that tells you how many coins, and what kind, the facility has made lately. From there escalators rise a couple of floors to two long halls that overlook the mint factory floor. Along the halls, at least where there are no windows to look through, are displays about the manufacture of coins: blanking, annealing, riddling, upsetting, striking, inspecting, counting and bagging.

In front of a display about mint marks, I fell into a short discussion with an elderly couple about them. The displays said, naturally, that until fairly recently Philadelphia-made coins had no mint mark — except for ’40s wartime nickels — but that they do now, except for the penny. As we talked about that, I was astonished to realize that they’d never heard of mint marks, though I didn’t tell them that. The woman thought it a nifty thing to learn, and said that she’d be looking more closely at coins. I encouraged her to do so.

Wiki, though there’s no underlying reference, explains why Philadelphia pennies carry no mint mark, something I’d never seen clarified: “Currently, the Lincoln cent is the only coin that does not always have a mint mark, using a D when struck in Denver but lacking a P when ostensibly struck at the Philadelphia mint; this practice allows additional minting of the coin at the San Francisco mint (S) and West Point mint (W) without the use of their respective mint marks to supplement coin production without the concern of creating scarce varieties. Generally modern S and W coins do not circulate, being mostly produced as bullion, commemorative, or proof coinage.”

I can’t say that I understood by sight much of what was going on down at the Philadelphia mint factory floor. There are a lot of large machines, along with conveyor belts and other mechanical odds and ends down there, but few people. Mostly the process, from blanking to bagging, is automated. I got the same impression of bemusing industrialism at the Denver mint in 1980, and at the Canberra mint in 1991, (the Osaka mint had a museum, but I don’t think it gave tours).

The factory is unusual in that way down on the floor is a scattering of coins, mostly pennies, presumably those that have dropped from the process at one time or another. For that matter, most of what I saw in various bins and tubs were pennies. Many, many pennies. All that manufacturing effort for a coin no one really wants any more, except for the zinc barons.

It may be just as well when the U.S. cent coin finally dies, as well as the dollar bill. If coins in this country are to have a long-term future — and I’d be sad to think of a future without them — very small denominations need to make way for larger ones. As long as the design is interesting, and the presidential dollars certain qualify, transitioning to $1 coins would be OK. So would $2 coins, for that matter, as the Canadians have done with their loonies and twonies.