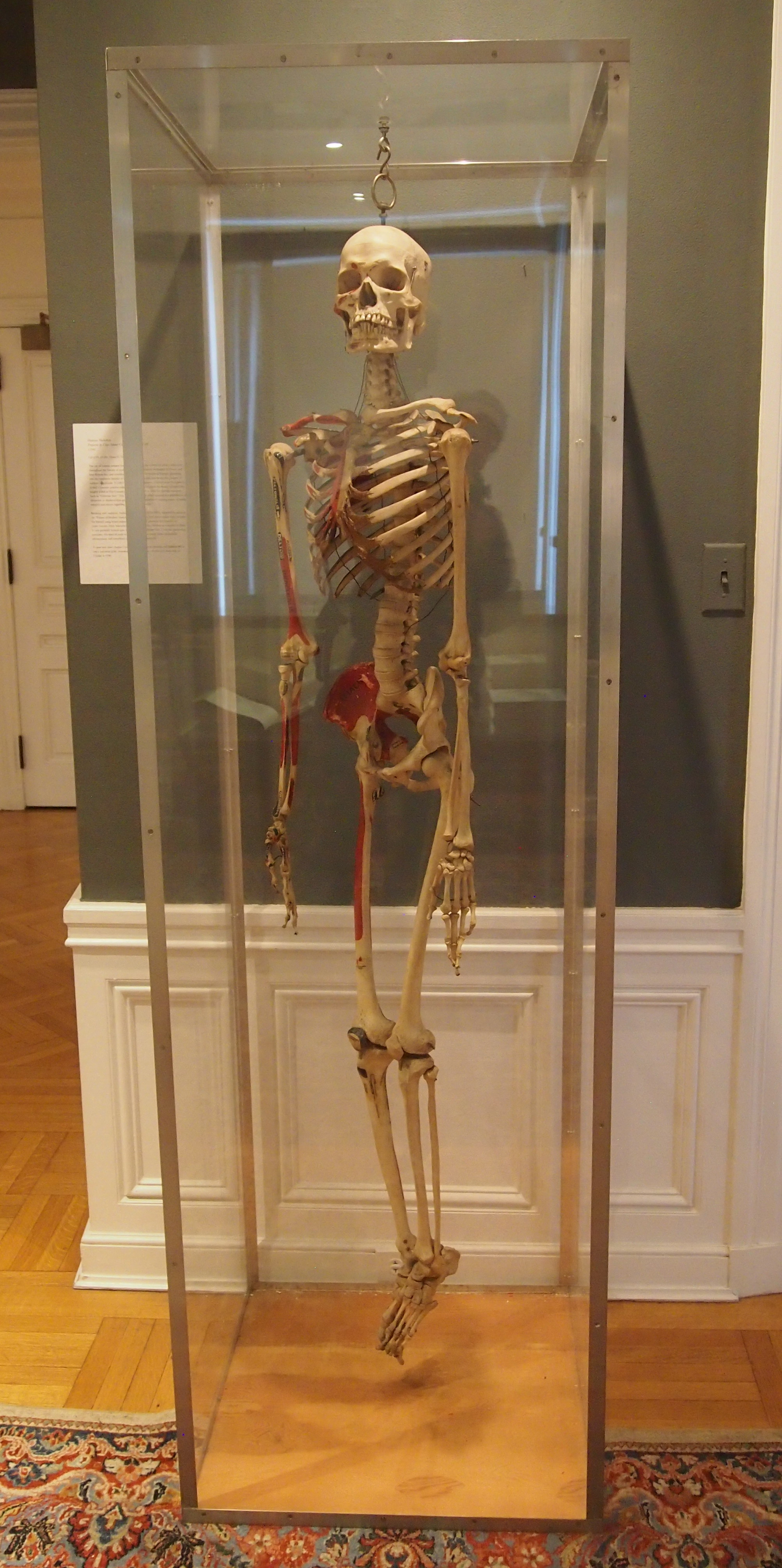

Want to see some particularly good momento mori? Look no further than the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago. I visited recently and came face to face with these fellows.

Also, a fuller version.

Also, a fuller version.

Glad I didn’t see these exhibits when I was a kid. I found skulls and skeletons particularly creepy then, which I guess is a fairly common feeling among youngsters.

Glad I didn’t see these exhibits when I was a kid. I found skulls and skeletons particularly creepy then, which I guess is a fairly common feeling among youngsters.

The feeling is long gone. Now I look at a skull and wonder, who was that? How did his headbone come to be here, instead of in the ground, or made into ashes?

The museum is a division of the International College of Surgeons, which is headquartered on Lake Shore Drive and includes about 10,000 square feet of public galleries committed to the history of surgery. Much more than skulls and bones. A good deal more, mainly artifacts from the history of cutting people for their own good, as well as other aspects of medicine.

There’s a large array of surgical tools from the last few centuries, medical machines from the late 19th century onward (such as antique x-ray machines), photos, paintings, drawings and a lot of reading material next to the exhibits. Some of the surgical tools, such as Civil War-vintage amputation kits, give me the willies more than any old skull could, even a trephined one.

Some paintings depict highlights from the history of surgery. Such as a copy of Rembrandt’s famed “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.”

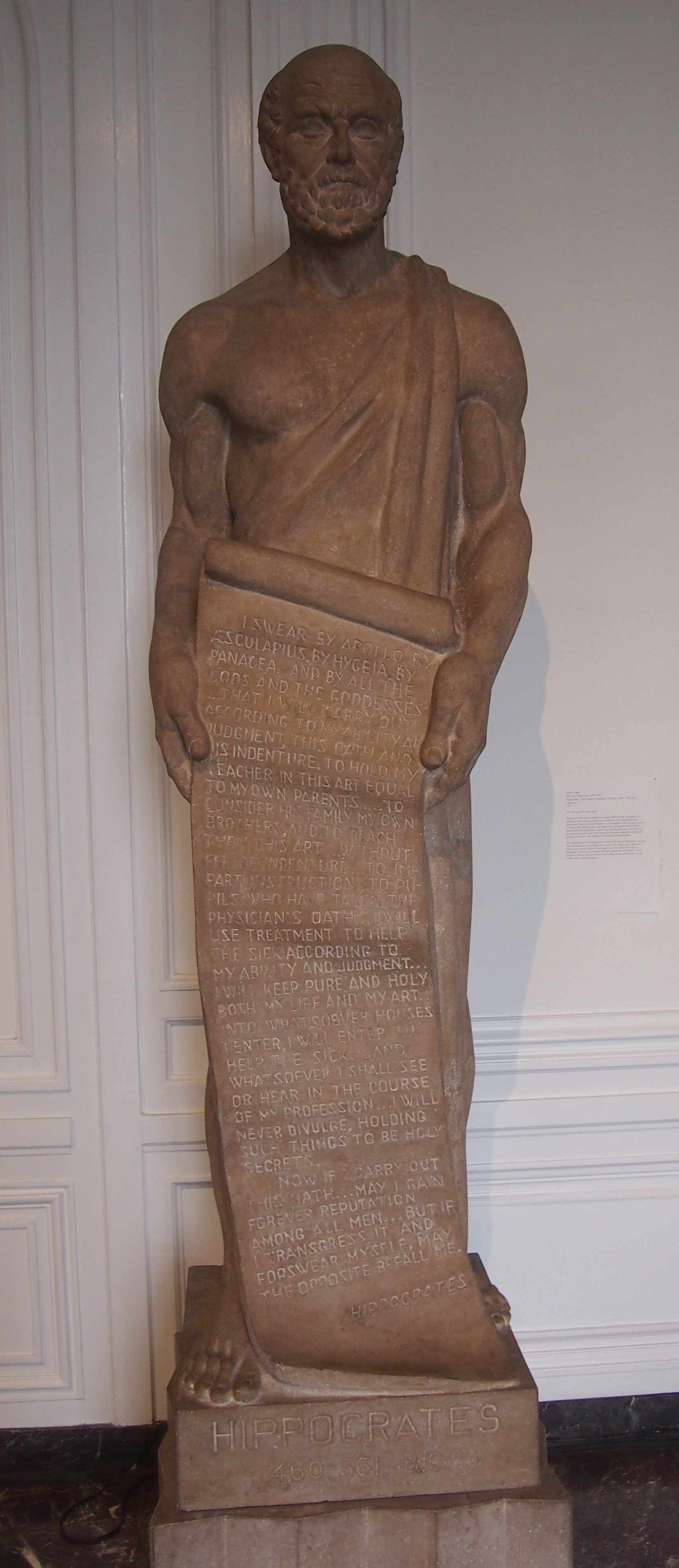

One room is given over to larger-than-life luminaries in the history of medicine — the “Hall of Immortals” — commissioned by the museum in its early days, in the 1950s, and mostly done by sculptor Louis Linck. That’s just old-fashioned enough to make me smile.

One room is given over to larger-than-life luminaries in the history of medicine — the “Hall of Immortals” — commissioned by the museum in its early days, in the 1950s, and mostly done by sculptor Louis Linck. That’s just old-fashioned enough to make me smile.

Included among the immortals are Imhotep, Hippocrates, Andreas Vesalius, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Ambroise Paré, Joseph Lister, and Marie Curie.

Included among the immortals are Imhotep, Hippocrates, Andreas Vesalius, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Ambroise Paré, Joseph Lister, and Marie Curie.

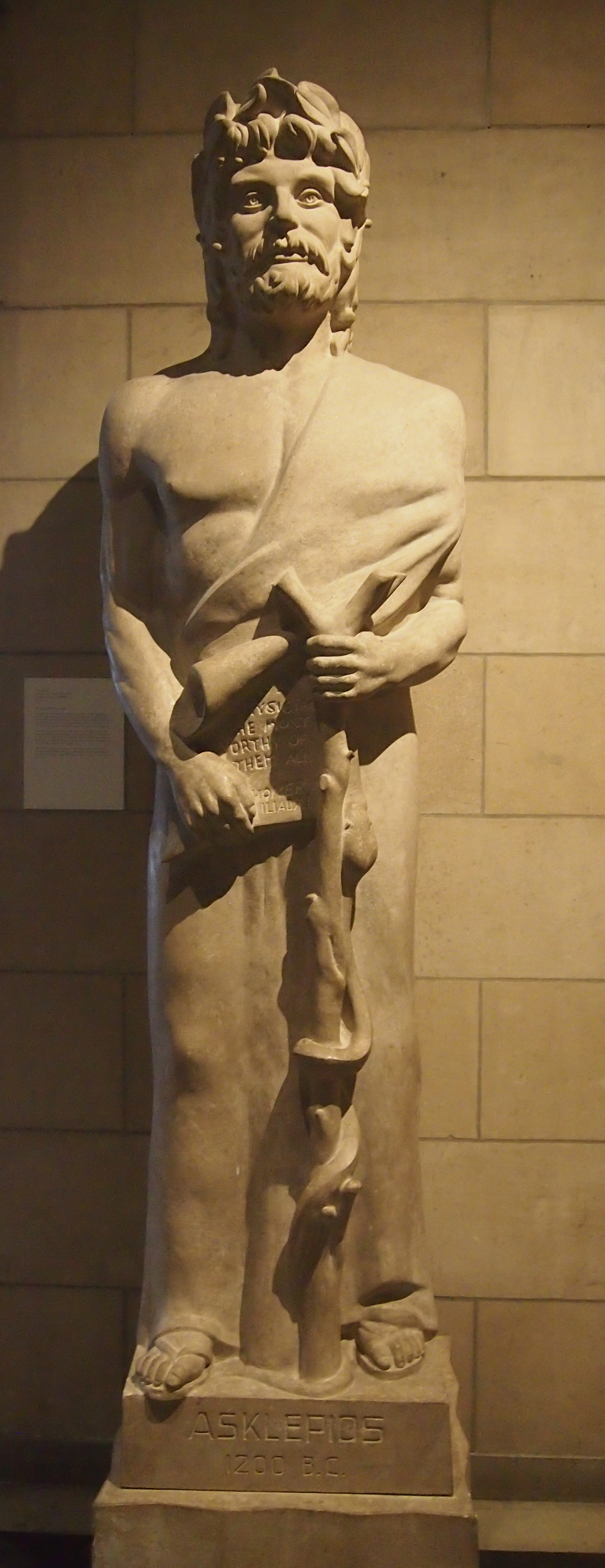

Just outside the Hall of Immortals is Asklepios, also by Linck.

Just outside the Hall of Immortals is Asklepios, also by Linck.

I suppose he wasn’t in the hall itself, since however much he’s part of the history of medicine, he isn’t an actual historic figure.

I suppose he wasn’t in the hall itself, since however much he’s part of the history of medicine, he isn’t an actual historic figure.