When I was young, I was a fan of the Texas highway maps produced by the Texas Highway Department (these days TexDOT), which were published annually and usually available at highway rest stops, though I think one year in the early ’70s I wrote to the department, and it mailed me one.

I admired those maps, unconsciously at that age, for good reasons. They were precise, easy to understand, useful and aesthetic, everything you need in a map. I found the color scheme for the cities and towns particularly fascinating. The largest cities were yellow. Mid-sized cities were green and large towns were brown. Or maybe those last two were the other way around; I don’t have an old map in front of me. To my thinking, that’s a brilliant way to depict population centers by relative size.

My 7th-grade Texas History teacher, the prickly Mrs. Carico, taught us map-reading skills one day using Texas highway maps. Imagine any teacher doing that now. I think I already knew most of what she said, though I did learn from her the difference between red mileage numbers (marked with red arrows) and black numbers that didn’t use arrows.

She didn’t care for the yellow-green-brown system, though I don’t remember why. Maybe because the national forests in East Texas and Big Bend National Park in West Texas were a slightly different shade of green. But I never found that confusing.

It’s probably from those maps that I got my first notion of Big Bend. There it was, hugging the Rio Grande, far from most everything else, thrusting into a remote part of Mexico, marked by the brown smears that denoted mountains on the map. A few roads went there. A few towns were nearby — but not that near. Somehow that place was a national park.

But I didn’t feel an aching need to go there. In 1972, when we took a family vacation to Carlsbad Cavern National Park, we could have just as easily have gone to Big Bend, but we didn’t, and the thought never occurred to me. In 1980, when I drove to El Paso from San Antonio, a little creativity on my could have resulted in a day in Big Bend, but it didn’t occur to me. In the 1990s, reports of his visits to the park by my brother Jay were interesting, but it seemed even further away than ever from my vantage in the Midwest.

Last year, I planned to go with Jay and Lilly, but circumstances prevented it. This year, I decided it was time, though by myself. So on April 24, 2018, in mid-morning, I found myself at the park entrance.

The road from the town of Marathon to the park entrance, U.S. 385, was a lonely one. I was almost by myself on the way down that morning. According to the National Park Service, Big Bend isn’t a top 10 national park by visitors. It isn’t even in the top 25.

The road from the town of Marathon to the park entrance, U.S. 385, was a lonely one. I was almost by myself on the way down that morning. According to the National Park Service, Big Bend isn’t a top 10 national park by visitors. It isn’t even in the top 25.

In 2017, it was 41st out of 60 national parks, and 130th out of all of the 377 units of the NPS (Gates of the Arctic NP is last among national parks, unsurprisingly). A lot people probably have the same feeling about Big Bend that I had for many years: I’m sure it’s scenic, but it’s far away.

Glad I made the effort. It’s well worth the drive.

Those views were even before I got to the main places I visited in the park, such as the Chisos Mountains.

The Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive winds south to the Rio Grande, through the Chihuahuan Desert landscape.

Ross Maxwell was easily the most scenic drive I’ve taken since the Icefields Parkway in the Canadian Rockies. What is it about mountains, wet or dry?

Ross Maxwell was easily the most scenic drive I’ve taken since the Icefields Parkway in the Canadian Rockies. What is it about mountains, wet or dry?

Though it was very warm — upper 80s F., I’d say — I had a hat, sunscreen and water, so I took some walks. One was down into a shallow valley to the former Homer Wilson ranch, to see the abandoned buildings.

No one else was on the trail, going there or back. It was on this short hike that I appreciated the quiet of the park. In a city, or the suburbs, the din of traffic is always coming from all directions, strongly or faintly, except maybe right after a large snowstorm.

In the remote Chihuahua Desert, if you hear a car, it’s a single car, and it goes away. Mostly you hear the wind, birds, and your footsteps, until you stand still. Listening for traffic and not hearing it was as much a pleasure as drawing in air without any hint of pollution.

I also spent time on foot in the Chisos Basin, but the best walk by far was into Santa Elena Canyon on the Rio Grande. At that point, the limestone cliffs of the canyon are 1,500 feet high and as majestic as anything I’ve seen in nature. Photos do the massive shapes little justice, but I took some anyway.

The trail led a short way into the canyon, and up some hundreds of feet. I was exhausted by the time I got up into it, but the view of the Rio Grande from that vantage was some compensation. Sure, let’s build a wall here.

The trail led a short way into the canyon, and up some hundreds of feet. I was exhausted by the time I got up into it, but the view of the Rio Grande from that vantage was some compensation. Sure, let’s build a wall here.

When I got back to the river, I took off my shoes and put my feet in. Cool but not cold, and it felt good.

It’s a Chabad Lubavitch “mitzvah tank.” Further investigation — the tank has its own

It’s a Chabad Lubavitch “mitzvah tank.” Further investigation — the tank has its own

Near the main entrance, I saw this wood carving.

Near the main entrance, I saw this wood carving.

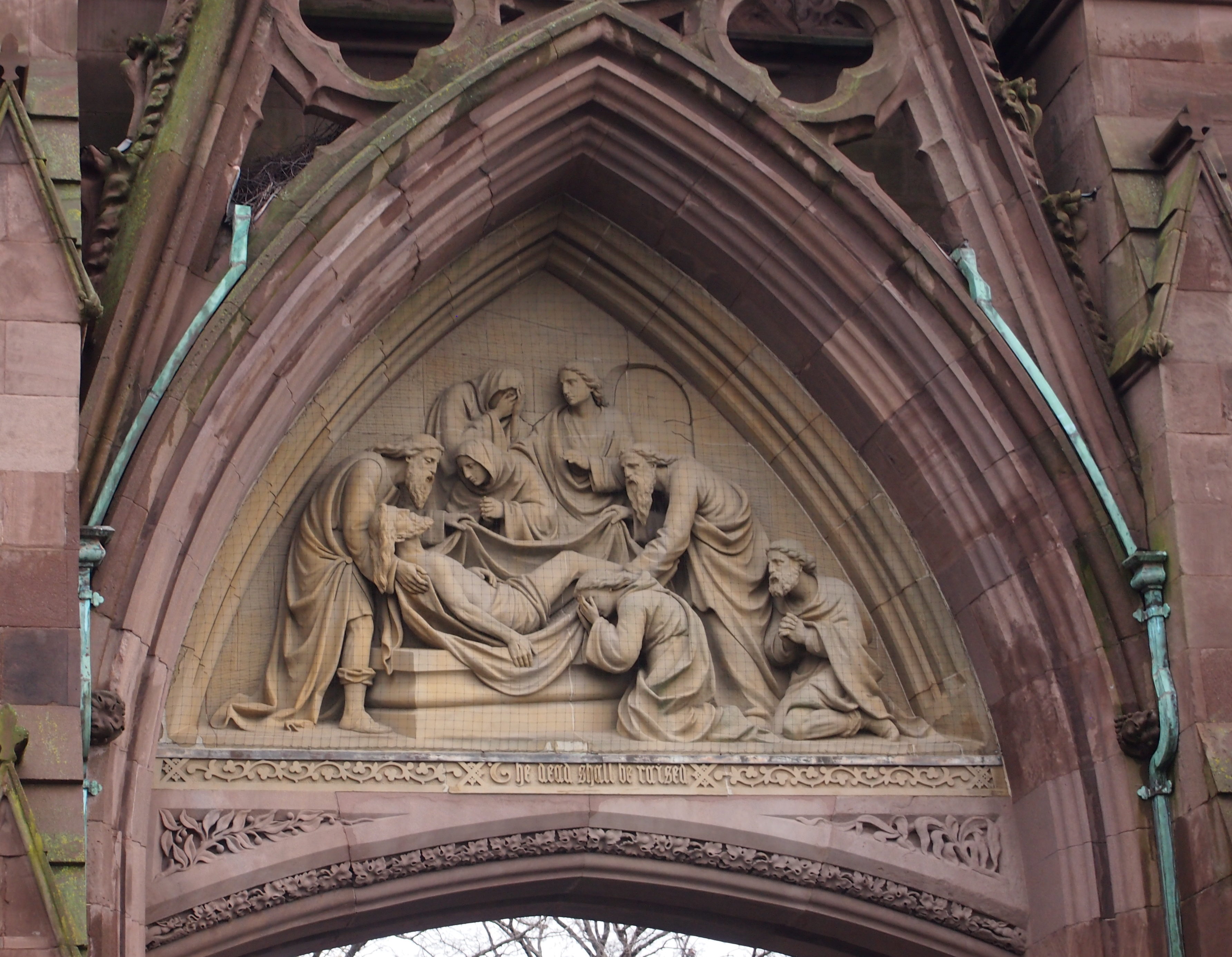

We soon came to the highest point in the cemetery, and in fact in Brooklyn, called Battle Hill for its part in a bloody episode in the Battle of Long Island (a.k.a. the Battle of Brooklyn) in the Revolution.

We soon came to the highest point in the cemetery, and in fact in Brooklyn, called Battle Hill for its part in a bloody episode in the Battle of Long Island (a.k.a. the Battle of Brooklyn) in the Revolution. On a clear day, you can see the Statue of Liberty from Minerva’s perch, but we didn’t have a clear day. I understand that that particular the sightline is protected by law, like views of the capitol in Austin.

On a clear day, you can see the Statue of Liberty from Minerva’s perch, but we didn’t have a clear day. I understand that that particular the sightline is protected by law, like views of the capitol in Austin.

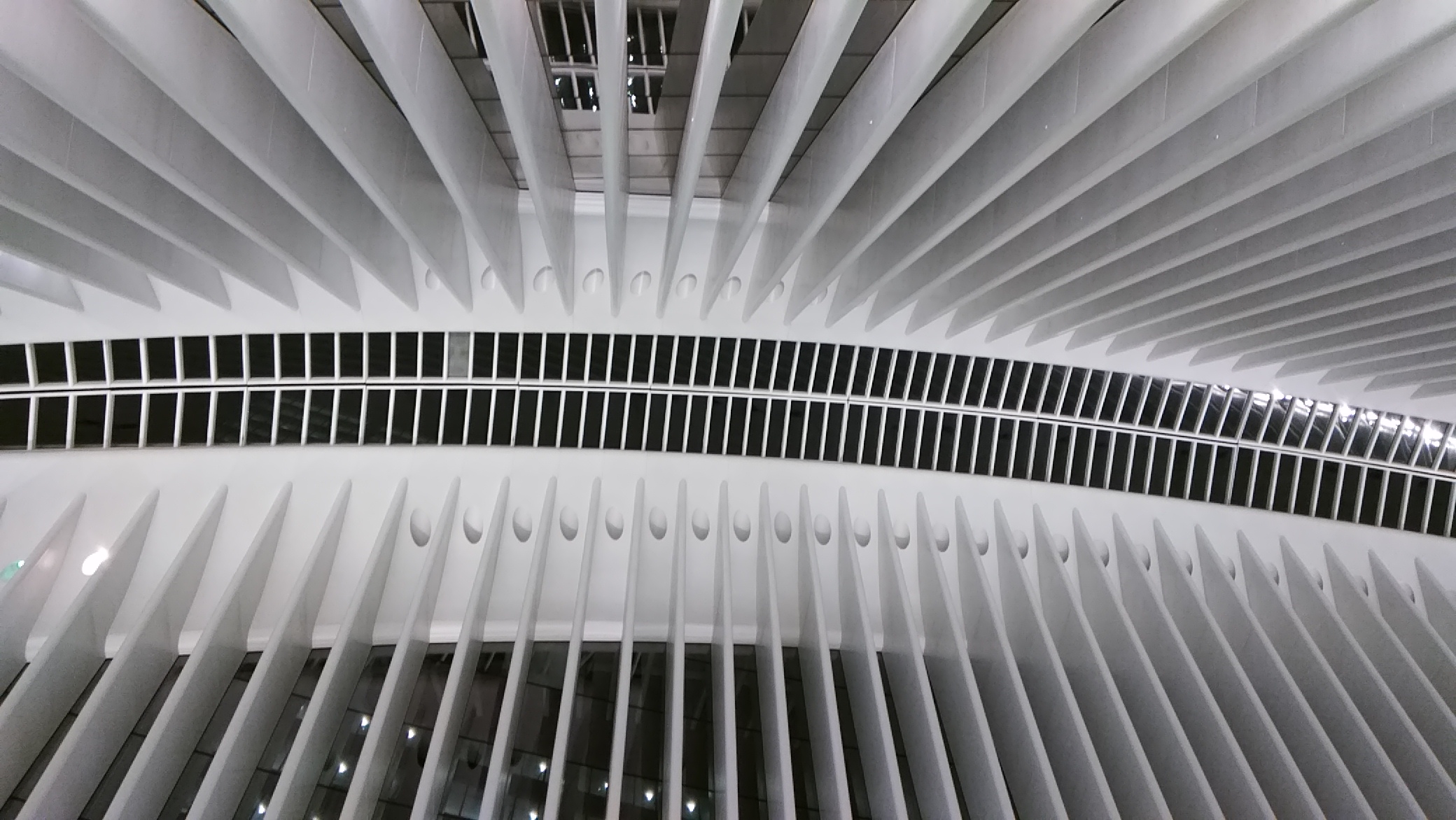

I’d walked to the Oculus from the Downtown restaurant where Geof and his wife Karen and I had had dinner. They wanted to show me the Oculus.

I’d walked to the Oculus from the Downtown restaurant where Geof and his wife Karen and I had had dinner. They wanted to show me the Oculus.

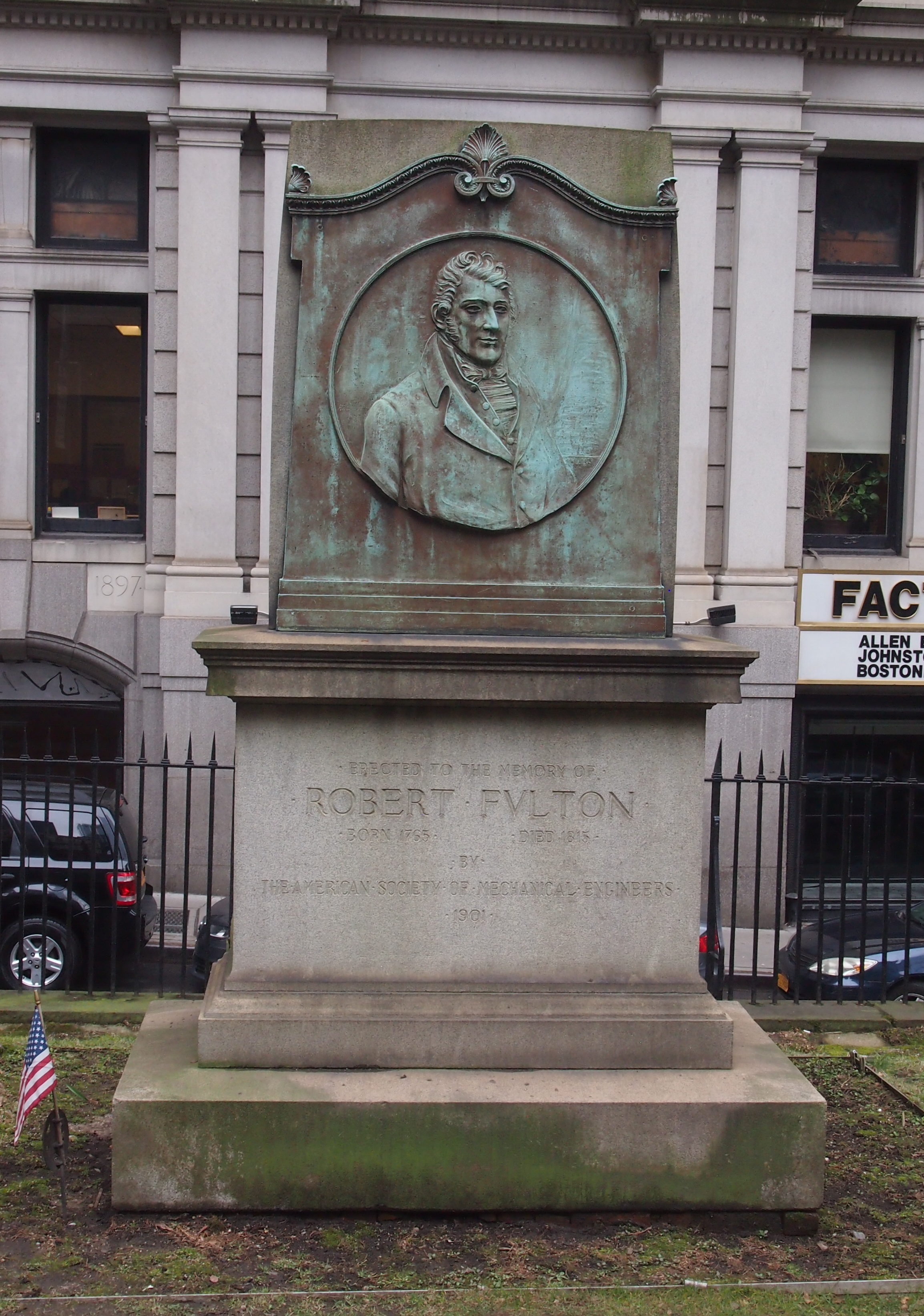

I have to admit that I either didn’t know, or had forgotten, that he is buried at Trinity. In a way, that was a good thing, since it was a nice surprise.

I have to admit that I either didn’t know, or had forgotten, that he is buried at Trinity. In a way, that was a good thing, since it was a nice surprise.