“Charging Bull,” a 7,100-pound bronze at Broadway and Whitehall St. in Downtown Manhattan, seems even more popular than the statue of Rocky Balboa in Philadelphia, which certainly has its fans. My evidence is only anecdotal, judging by the number of people I saw around each, trying to take a picture. Rocky had a short line of people waiting to take their picture with him (in 2016, some 40 years after the movie came out).

But the Bull draws a crowd. In front of it:

Along with those eager to shoot its backside:

Along with those eager to shoot its backside:

I was in New York City all of last week, where I met many of the editors of the company I now work for, plus writers and other staff, at an office in Downtown (Lower) Manhattan. Also during the trip, I spent time with a few old friends and their spouses, and my youngest nephew and his girlfriend. I even had a little time to walk around town, especially Downtown, which I enjoyed despite chilly air and some drizzle.

I was in New York City all of last week, where I met many of the editors of the company I now work for, plus writers and other staff, at an office in Downtown (Lower) Manhattan. Also during the trip, I spent time with a few old friends and their spouses, and my youngest nephew and his girlfriend. I even had a little time to walk around town, especially Downtown, which I enjoyed despite chilly air and some drizzle.

One of my walks took me to “Charging Bull,” which had its start as one of the heaviest works of guerilla art ever made, by Arturo Di Modica in the late 1980s. Now it’s a fixture on the tourist circuit, located almost as far south as you can go on the island, though not quite.

As is “Fearless Girl,” a much newer installation by Kristen Visbal, dating only from last year, and which was positioned to face the bull as an ad for an exchange-traded fund. I watched as one person after another posed with “Girl.”

Apparently Di Modica doesn’t like his work being upstaged by a little girl, but I can’t say that I much care. What’s interesting to me is their power as tourist magnets. Not many statues have that.

Apparently Di Modica doesn’t like his work being upstaged by a little girl, but I can’t say that I much care. What’s interesting to me is their power as tourist magnets. Not many statues have that.

The statues are adjacent to a nice little park that has the distinction of being the first public park in New York, Bowling Green.

Note the fence. It rates a plaque, which says that the park was “leased in 1733 for use as a bowling green at a rental of one peppercorn a year. Patriots, who in 1776 destroyed an equestrian statue of George III which stood here, are said to have removed the crowns which capped the fence post, but the fence itself remains.”

Note the fence. It rates a plaque, which says that the park was “leased in 1733 for use as a bowling green at a rental of one peppercorn a year. Patriots, who in 1776 destroyed an equestrian statue of George III which stood here, are said to have removed the crowns which capped the fence post, but the fence itself remains.”

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Customs House rises over the park, roughly where Fort Amsterdam stood long ago.

The present structure dates from the early 1900s and was designed by Cass Gilbert, who’s best known for the Woolworth Building further uptown. These days, the building is home to a branch of the National Museum of the American Indian, which is part of the Smithsonian, as well as the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York.

The present structure dates from the early 1900s and was designed by Cass Gilbert, who’s best known for the Woolworth Building further uptown. These days, the building is home to a branch of the National Museum of the American Indian, which is part of the Smithsonian, as well as the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York.

Off to each side of the building, allegorical figures stand above; tourists loll below.

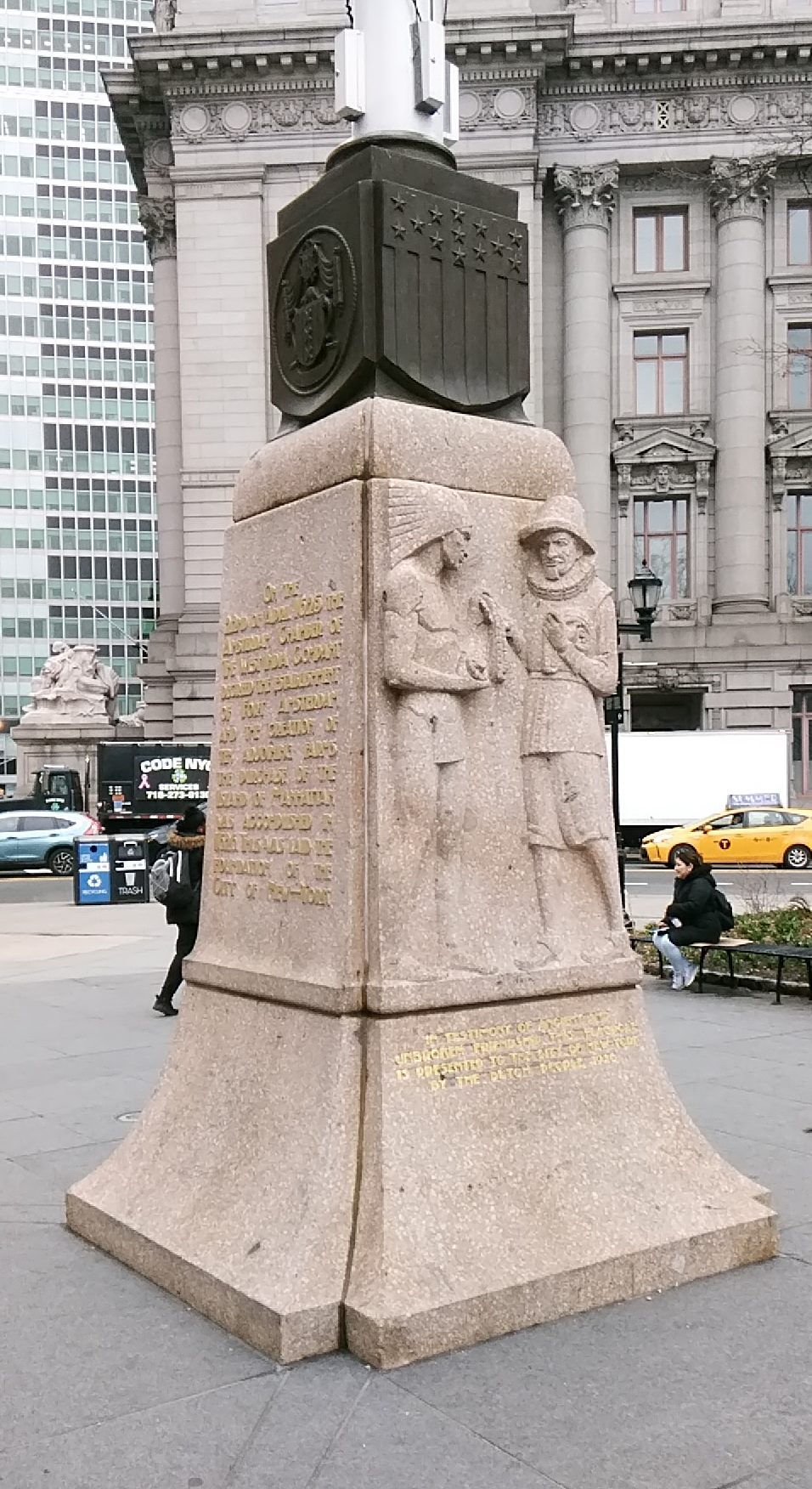

Across State Street from the building, in Battery Park, is a curious flagpole. Officially it’s the Netherland Monument. This is the base.

Across State Street from the building, in Battery Park, is a curious flagpole. Officially it’s the Netherland Monument. This is the base.

According to NYC Parks: “This monumental flagstaff commemorates the Dutch establishment of New Amsterdam and the seventeenth century European settlement which launched the modern metropolis of New York City. Designed by H.A.van den Eijnde (1869-1939), a sculptor from Haarlem in the Netherlands, the monument was dedicated in 1926 to mark the tercentenary of Dutch settlement, and the purchase of the island of Manhattan from Native Americans.”

How many people crowd around the bronze bull? Dozens at a time. Around the Dutch flagpole? None. Fitting, I guess. Bulls used to get their own cults. Flagpoles, not so much.

The Dutch flag wasn’t flying on the pole.

But at least I saw New York City flag, which is based on the tricolor of the Prince’s Flag of the Dutch Republic. Not as striking as the Chicago flag, but not bad at all.

But at least I saw New York City flag, which is based on the tricolor of the Prince’s Flag of the Dutch Republic. Not as striking as the Chicago flag, but not bad at all.