Besides the Briscoe, last Tuesday I visited the San Antonio Museum of Art, which is just north of downtown and also happens to be no charge in the late afternoon and early evening every Tuesday.

The SAMA complex is a major adaptive reuse project from the 1980s. The former Lone Star Brewery, whose solid brick buildings dated from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was transformed into the museum, complete with neon-decorated skybridge on the fourth floor. Sounds Vegas-like, but it isn’t garish.

The SAMA complex is a major adaptive reuse project from the 1980s. The former Lone Star Brewery, whose solid brick buildings dated from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was transformed into the museum, complete with neon-decorated skybridge on the fourth floor. Sounds Vegas-like, but it isn’t garish.

The museum has a sizable collection befitting its location in a sizable city, including ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman art, North American, Latin American and Spanish colonial pieces, collections representing Japan, Korea, and India, three galleries of Chinese works from early times to later dynasties, Near Eastern art, an Oceania gallery and more.

I decided to focus on two of the museum’s strengths — art from Antiquity, especially Rome, and Latin American folk art — though I did spend some time looking at American paintings and Texas artwork.

Here’s something that gets your attention, or ought to, right when you enter SAMA’s commodious Roman art gallery.

A second-century CE statue known as the Landsdowne Marcus Aurelius. Wonder what the original colors looked like.

A second-century CE statue known as the Landsdowne Marcus Aurelius. Wonder what the original colors looked like.

“Begun by Gavin Hamilton (1723-98), one of the most prominent British explorers of classical sites of the eighteenth century, the Lansdowne Collection came to hold more than one hundred stellar examples of classical statuary, displayed in a specially designed gallery in Lansdowne House in London,” says a blurb for Reconstructing the Landsdowne Collection of Classical Marbles.

“The collection, however, was dispersed in the years after 1930, and its works are now scattered across the globe.”

This particular one wound up at SAMA, a donation of the 20th-century American owner of the piece, a rich fellow I’ve run across before: Gilbert Denman Jr. In fact, he left his collection of ancient art to the museum, making the gallery possible.

Another Denman bequest: the Lansdowne Trajan. The Romans were clearly not shy about official nudity.

Another Denman bequest: the Lansdowne Trajan. The Romans were clearly not shy about official nudity.

A beat-up portrait of Hadrian.

A beat-up portrait of Hadrian.

Here’s something you don’t see every day: Etruscan art.

In this case, a lid from a sarcophagus. Considerably worn, with an unsettling face that looks at us from across 25 centuries or so. As historical peoples go, the Etruscans are a half-remembered fragment of a haruspical dream.

In this case, a lid from a sarcophagus. Considerably worn, with an unsettling face that looks at us from across 25 centuries or so. As historical peoples go, the Etruscans are a half-remembered fragment of a haruspical dream.

I also spent time at the Latin American Folk Art gallery, which is part of the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Latin American Art. Rockefeller had his hobbies, and one of them was collecting Latin American folk art.

As the NYT reported when the center opened about 20 years ago: “When Nelson A. Rockefeller made his final trip to Mexico in 1978, several months before his death, his eye was drawn to a small hacienda surrounded by a picket fence along a rural road in Oaxaca. Atop each picket was a tall, strangely striking figurine made of rough pottery.

“The former Vice President stopped the car, walked to the door and discovered the shop of a family of potters. Each statue on the fence had been damaged somehow in the making and just perched on the fence to help advertise the shop. They were evocative pieces spanning many years, left to bake in the Mexican sun. Rockefeller bought them all.”

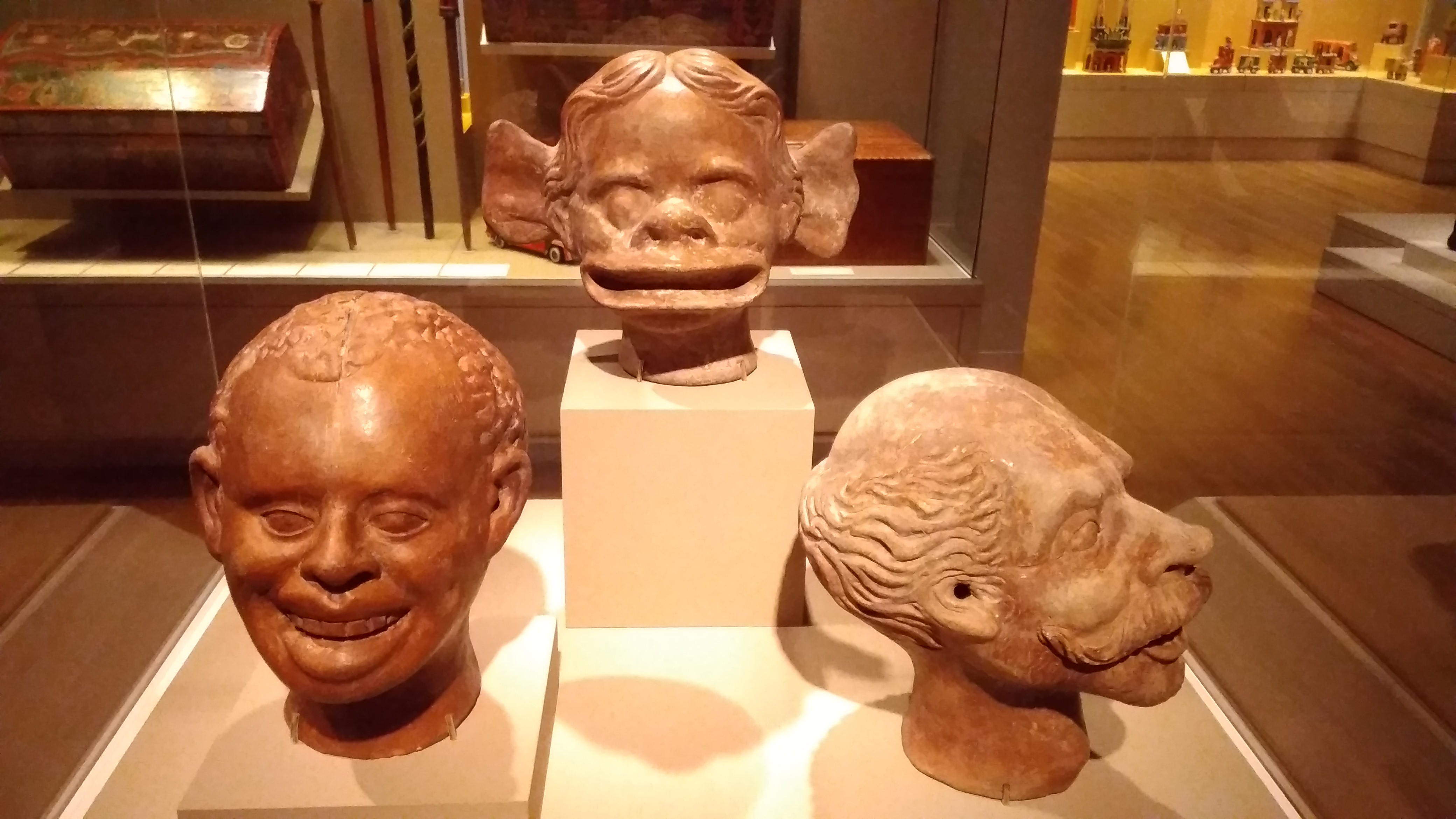

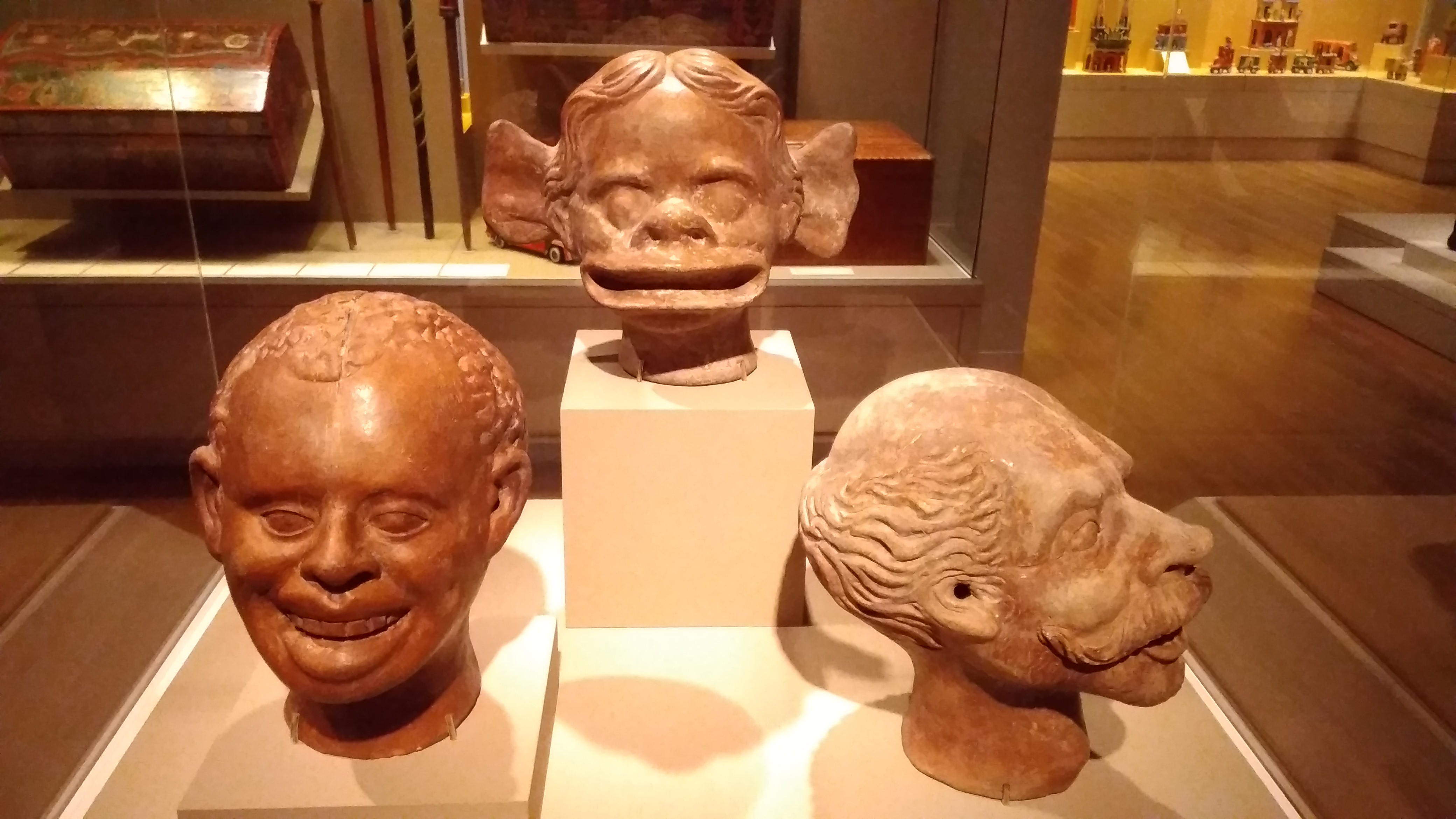

These fellows greet you at the gallery.

Molds for papier mache figures, ca. 1930, artist unknown, from Celaya, Mexico.

Molds for papier mache figures, ca. 1930, artist unknown, from Celaya, Mexico.

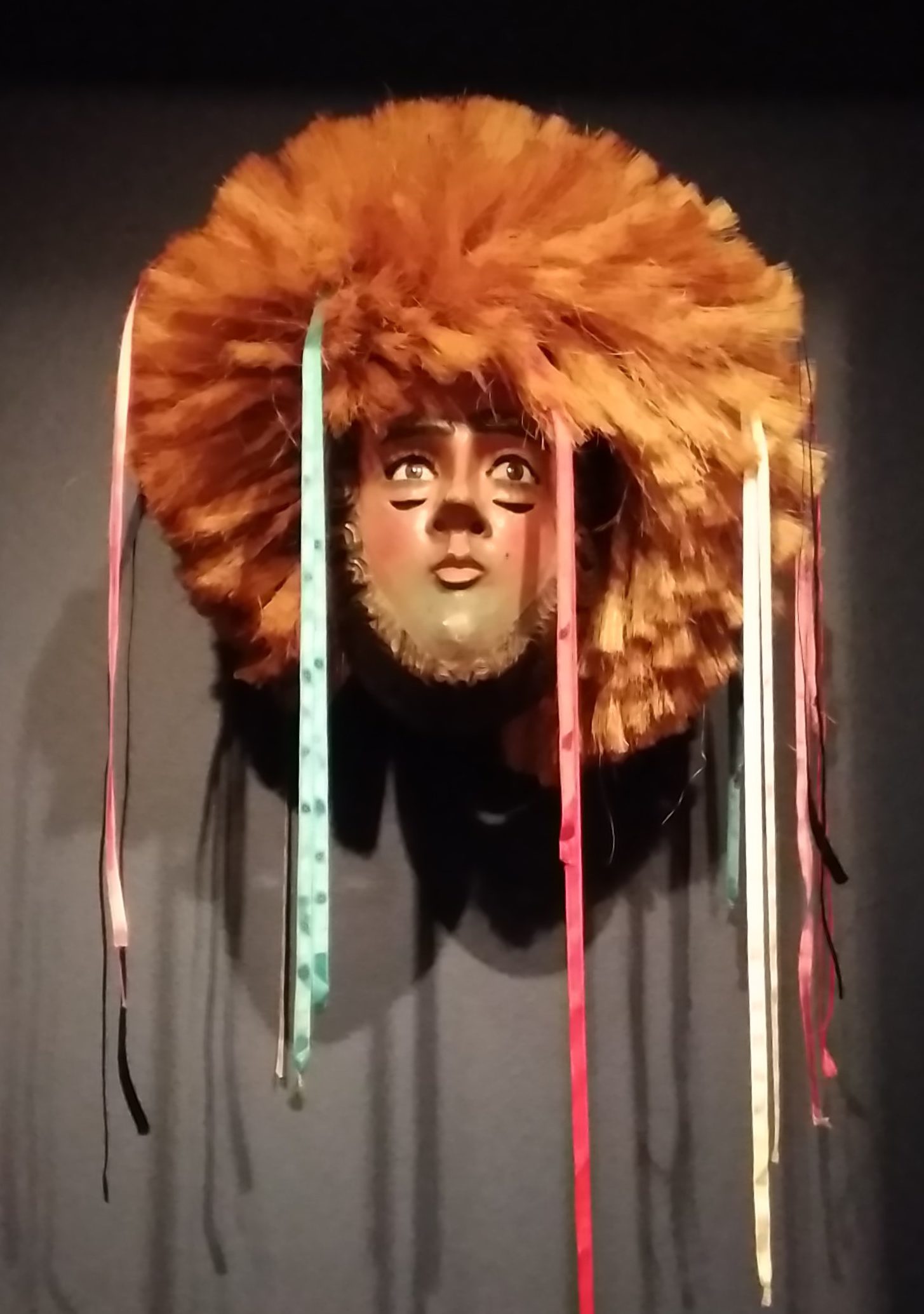

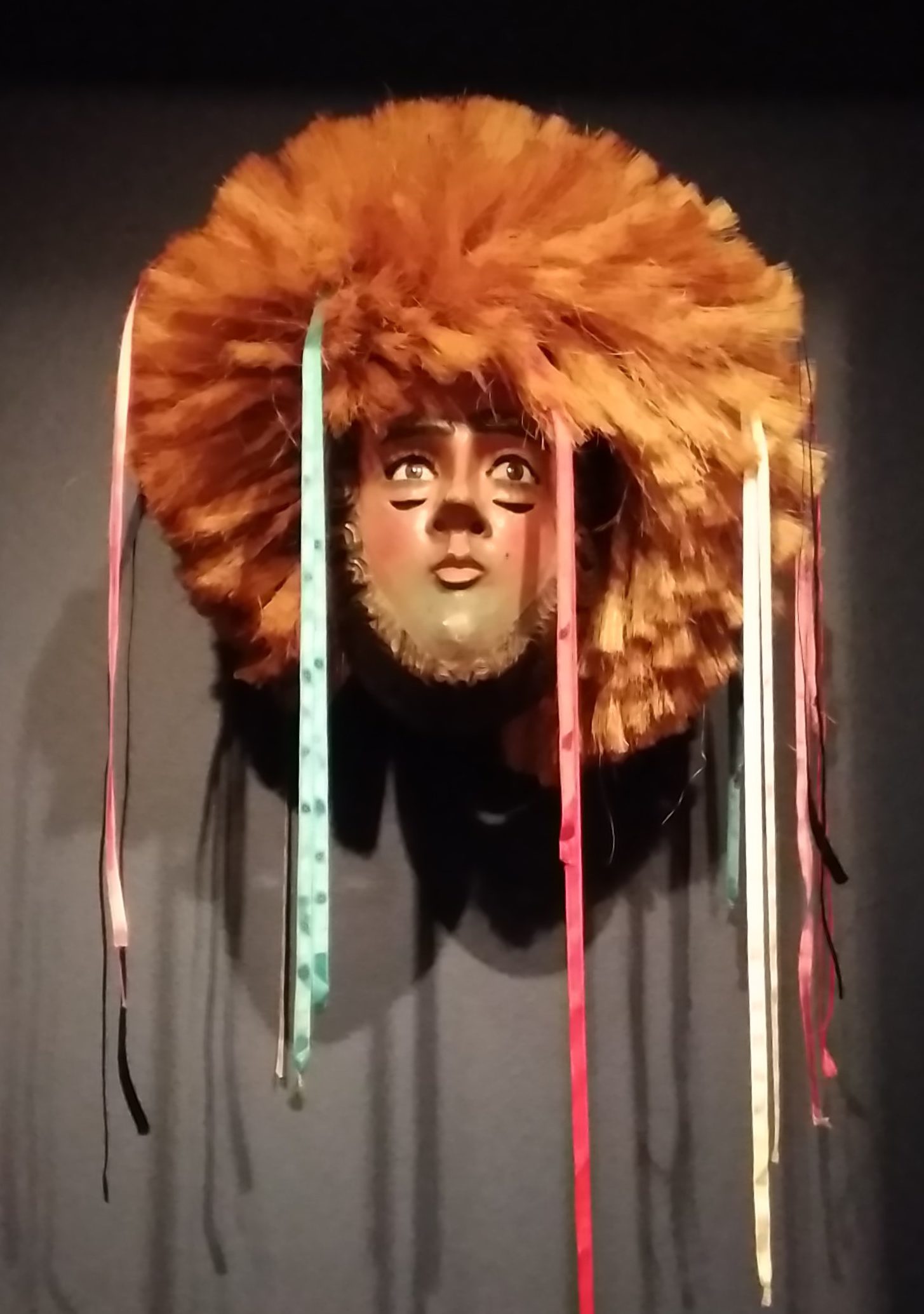

The work of another unknown artist.

A Parachico Mask (Mascara de Parachico) from Chiapas, Mexico. Polychromed wood, glass, ribbon and cactus fiber. Ca. 1970 and about as funky as can be.

A Parachico Mask (Mascara de Parachico) from Chiapas, Mexico. Polychromed wood, glass, ribbon and cactus fiber. Ca. 1970 and about as funky as can be.

By contrast, the artist of these delightful creations is well known.

They’re painted earthenware by Candelario Medrano, a Mexican artist who died in 1988. “Medrano began his career by producing toy whistles, mermaids, roosters, and other animals,” the museum says. “Later, he placed them on airplanes, boats, towers, merry-do-rounds and trucks, thereby creating delightful and colorful scenes of fantasy.”

They’re painted earthenware by Candelario Medrano, a Mexican artist who died in 1988. “Medrano began his career by producing toy whistles, mermaids, roosters, and other animals,” the museum says. “Later, he placed them on airplanes, boats, towers, merry-do-rounds and trucks, thereby creating delightful and colorful scenes of fantasy.”

As usual, the museum isn’t selling postcards based on artwork that would make unusual cards, like this.

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

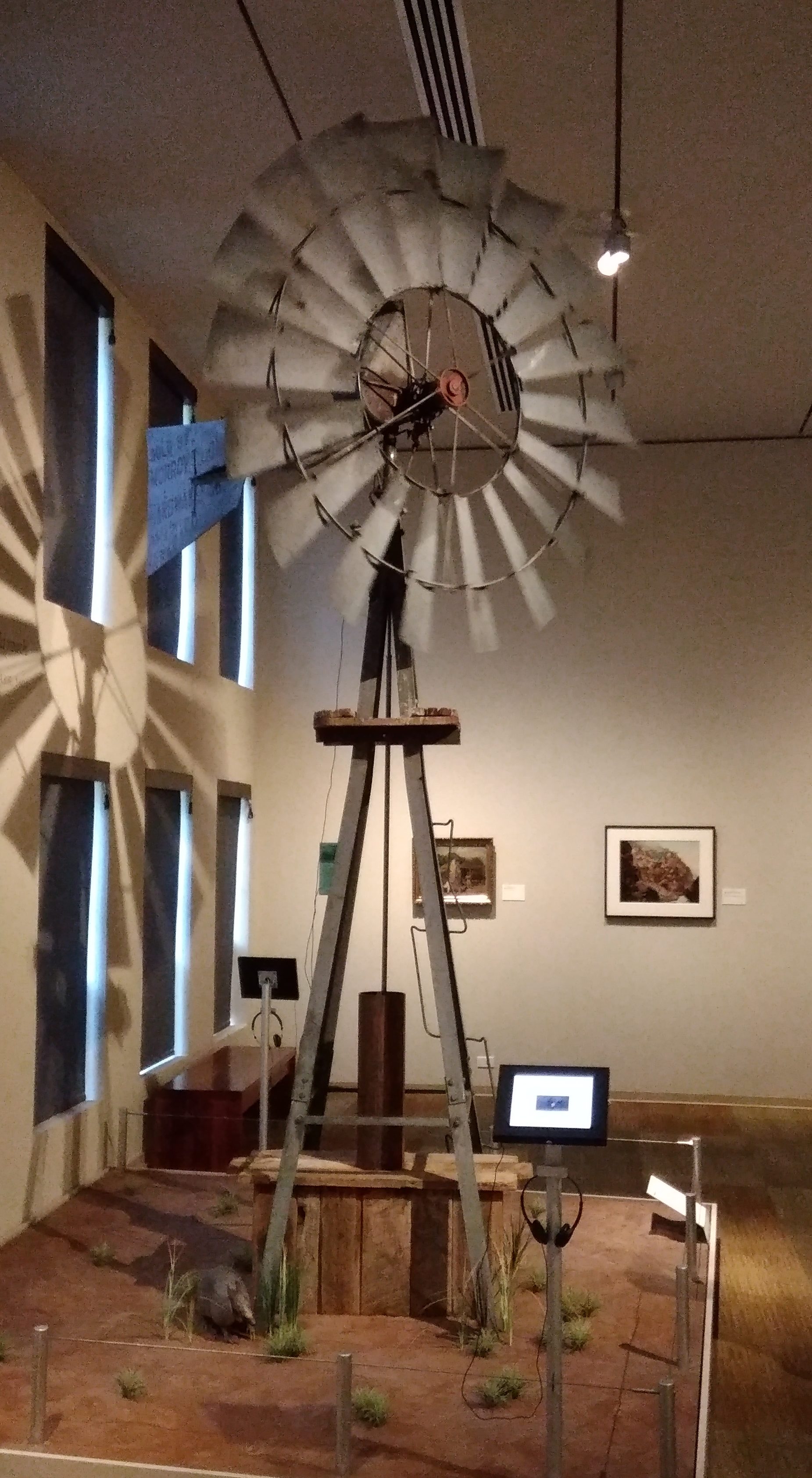

And down toward the ground, where strange critters lurk.

And down toward the ground, where strange critters lurk. So pleasant that I’m taking a week off from work and posting. Back on August 5.

So pleasant that I’m taking a week off from work and posting. Back on August 5. Temps were in the 90s, of course, which might have contributed to it, but I suspect not many people come this way anyway.

Temps were in the 90s, of course, which might have contributed to it, but I suspect not many people come this way anyway. A view from the Arsenal Street Bridge, looking north toward downtown San Antonio.

A view from the Arsenal Street Bridge, looking north toward downtown San Antonio. The building poking over the trees, with the flag, is the Tower Life Building, though I’ll always think of it has the Smith-Young Tower, completed in 1929. One of the city’s finest office buildings. I understand that once upon a time, my civil engineer grandfather had an office there.

The building poking over the trees, with the flag, is the Tower Life Building, though I’ll always think of it has the Smith-Young Tower, completed in 1929. One of the city’s finest office buildings. I understand that once upon a time, my civil engineer grandfather had an office there.

This is the Arneson River Theatre.

This is the Arneson River Theatre. The stage is on the north side of the river, while 13 rows of grass are on the south side for seating. Just another idea of the Father of the Riverwalk, H.H. Hugman, finally realized as the WPA built the Riverwalk in the late ’30s. Arneson was the WPA engineer who was to have been in charge of building the Riverwalk, but he died before the project really got under way.

The stage is on the north side of the river, while 13 rows of grass are on the south side for seating. Just another idea of the Father of the Riverwalk, H.H. Hugman, finally realized as the WPA built the Riverwalk in the late ’30s. Arneson was the WPA engineer who was to have been in charge of building the Riverwalk, but he died before the project really got under way.

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

“Bird Woman” (2001) by

“Bird Woman” (2001) by

Edward Steves was a successful businessman in lumber in San Antonio in the 19th century, and Steves & Sons, which makes doors, is still around. I went to high school with a girl who was descended from Steves on her mother’s side.

Edward Steves was a successful businessman in lumber in San Antonio in the 19th century, and Steves & Sons, which makes doors, is still around. I went to high school with a girl who was descended from Steves on her mother’s side.