During my free moments recently, scant free moments on some days, I’ve been reading the Comics Curmudgeon. It’s a standard blog of long-standing. A fellow named Joshua Fruhlinger posts a selection of daily newspaper comics — to use the quaint old term — and adds commentary. Generally mocking commentary, but unlike so much writing in that vein, he writes well. Some of it is very funny, or at least highly amusing, and often enough thoughtful too.

The range of targeted comics is broad, including what could be called funnies, except they aren’t funny all that much, such as B.C., Beetle Bailey, Crankshaft, Family Circus, Hagar the Horrible, Lockhorns, Marvin, Pluggers, Shoe, Six Chix (one of the few I’d never heard of) and many others. But not, I see from the archives, Broom-Hilda. I guess some things are so bad, yet have so much inexplicable longevity, that mocking them is pointless.

Also lampooned are the few soap-opera or adventure comics that are still around, such as Mary Worth, Mark Trail, The Phantom and Rex Morgan M.D. From the blog I learned that Apartment 3-G expired a few years ago, an event that had completely escaped my notice. Say, whatever happened to Dondi?

Some samples:

Crock, Jan. 3, 2019, has one of the men talking to the fort’s cook: “Psst… the men are planning a coup for Crock.” As the soldier walks away in the second panel, the cook says, “Will they need any snacks or finger food?” (Shouldn’t that be a coup against Crock? Never mind.)

Comics Curmudgeon says: “Crock’s Foreign Legion detachment is based in an isolated fort surrounded by a hostile, barely subjugated colonial population, and so it probably relies on supplies from the metropole to avoid starvation. A violent overthrow of the fort’s commanding officer, no matter how cruel and incompetent he might be, will certainly be seen as an act of rebellion against the French Republic, and so our heroes are likely to be cut off from any outside support, at least until they can successfully negotiate an amnesty. Thus, the coup plotters need to ensure that the fort’s cook and his staff are on their side and prepared for the hardship to come! But they’re being kind of half-assed about it, in my opinion.”

Beetle Bailey, Oct. 10, 2016, has two panels. First, Sarge (in the lead) and Beetle are climbing a steep slope. “Keep going, Beetle! We’re almost to the top!” Sarge says. Beetle simply says, “Groan!”

Next, at a cliff’s edge, Sarge says, “Wow, Beetle! We made it! Congrats!” and slaps Beetle on the back. Beetle is shown flying off the cliff.

CC says: “Welp, looks like Sarge finally just straight-up murdered Beetle! I guess this strip is over now. Looking forward to seeing what new comic they replace it with, or maybe just enjoying the soothing blank space left over when they don’t bother!”

A single panel Heathcliff, July 15, 2013, shows the cat hitting a baseball, using a fish as a bat. The caption says, “He switched to a lighter flounder.”

CC says: “Today’s panel provides something more in line with the profound weirdness bubbling below the surface of this feature’s modern iteration. Cats like fish, and I suppose cats like “playing with their food,” when their food is alive, but instead here the tenuous conceptual cat-fish connection produced a scenario where Heathcliff has a collection of fish of varying densities that he uses as athletic equipment. How dead are these fish, anyway? Are they still floppy? Do they hit the ball with a meaty smack, or have they started to rot, with contact with any projectile producing a cloud of scattered fish-flesh?

On July 22, 2007, he astutely compared Shoe and Get Fuzzy on politics.

“… while usually I go on about just about everything at great length, the most important thing I can say here is that Get Fuzzy is funny, while Shoe isn’t. Shoe falls into the typical toothless trap of just saying “THE POLITICS AREN’T THEY ANNOYING?”, literally allowing the discussion to be replaced by meaningless placeholder syllables. Get Fuzzy works with established character traits — Bucky and Satchel’s party affiliations have been frequently noted, whereas I don’t believe Shoe and the Perfesser had political beliefs until they became necessary for this cartoon. Plus Get Fuzzy contains actual political jokes that are funny. I love the third-party punchline, but I love “Well, with the proper funding…” even more.

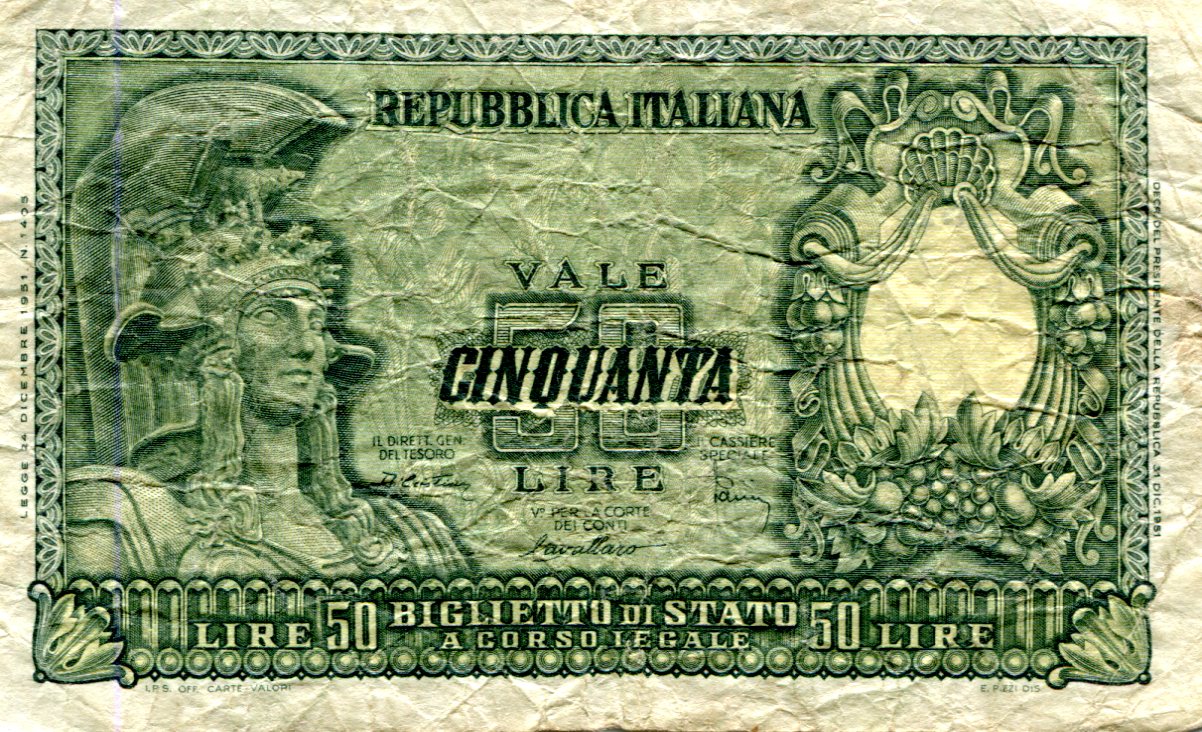

I’m not actually sure that’s the obverse, though Wiki says it is. I suppose the Arabic text determines that; the Roman text is on the other side. In any case, this side depicts the Sayeda Aisha Mosque in Cairo.

I’m not actually sure that’s the obverse, though Wiki says it is. I suppose the Arabic text determines that; the Roman text is on the other side. In any case, this side depicts the Sayeda Aisha Mosque in Cairo. Not just any eagle, either: the Eagle of Saladin. The 12th-century Sultan of Egypt and warrior against the Crusader states.

Not just any eagle, either: the Eagle of Saladin. The 12th-century Sultan of Egypt and warrior against the Crusader states.

The note is also small in size. Interestingly, exactly four inches long and two-and-a-half inches tall. Odd, I would have thought that the sides measure evenly in centimeters rather than inches.

The note is also small in size. Interestingly, exactly four inches long and two-and-a-half inches tall. Odd, I would have thought that the sides measure evenly in centimeters rather than inches. Who are these gentlemen who look so much alike, except the eyes of one are closer together than the other?

Who are these gentlemen who look so much alike, except the eyes of one are closer together than the other?