Our main destination on Saturday was the Field Museum. Been awhile since we’ve been there. Looks as sturdy as ever. An important consideration was that the museum charges no admission for Illinois residents during the entire month of February, representing a $69 savings for us. A savings in theory, because it’s unlikely we would have ever paid full price. Maybe half that. I don’t have the numbers at handy, but I strongly suspect that ticket prices have significantly outpaced inflation over recent decades, and that sticks in my craw.

An important consideration was that the museum charges no admission for Illinois residents during the entire month of February, representing a $69 savings for us. A savings in theory, because it’s unlikely we would have ever paid full price. Maybe half that. I don’t have the numbers at handy, but I strongly suspect that ticket prices have significantly outpaced inflation over recent decades, and that sticks in my craw.

Not that you don’t get a high-quality natural history museum for that price.

Not that you don’t get a high-quality natural history museum for that price.

Something I didn’t know before: the main hall, the grand, sweeping main hall of the Field Museum, which measures about 21,000 square feet, and whose ceiling reaches up 76 feet, actually has a formal name: Stanley Field Hall. He was Marshall Field’s nephew, but more than that, president of the museum for a long time, from 1908 to 1964.

T. rex Sue, the museum’s most famed — and marketed — artifact, isn’t in the hall any more. Those bones occupy their own room these days, more about which later.

T. rex Sue, the museum’s most famed — and marketed — artifact, isn’t in the hall any more. Those bones occupy their own room these days, more about which later.

Rather, an exhibit called Máximo now lords over the hall, at 122 feet across and 28 feet tall at the head. Not actual bones, but a model cast from a titanosaur discovered in Patagonia, and considered its own species, Patagotitan mayorum, only since 2018.

Still, it’s impressive.

After the main hall, we spent time at the Granger Hall of Gems, the Malott Hall of Jades and at a display of meteorites. Last time I visited the museum, we were promised that there would soon be a permanent exhibit of pieces of the Chelyabinsk Meteor, which fell to Earth in Russia in 2013.

After the main hall, we spent time at the Granger Hall of Gems, the Malott Hall of Jades and at a display of meteorites. Last time I visited the museum, we were promised that there would soon be a permanent exhibit of pieces of the Chelyabinsk Meteor, which fell to Earth in Russia in 2013.

Here they are.

Not that large, but I think every bit as interesting as the dinosaurs. I’ve always had more fondness for astronomy than paleontology.

Not that large, but I think every bit as interesting as the dinosaurs. I’ve always had more fondness for astronomy than paleontology.

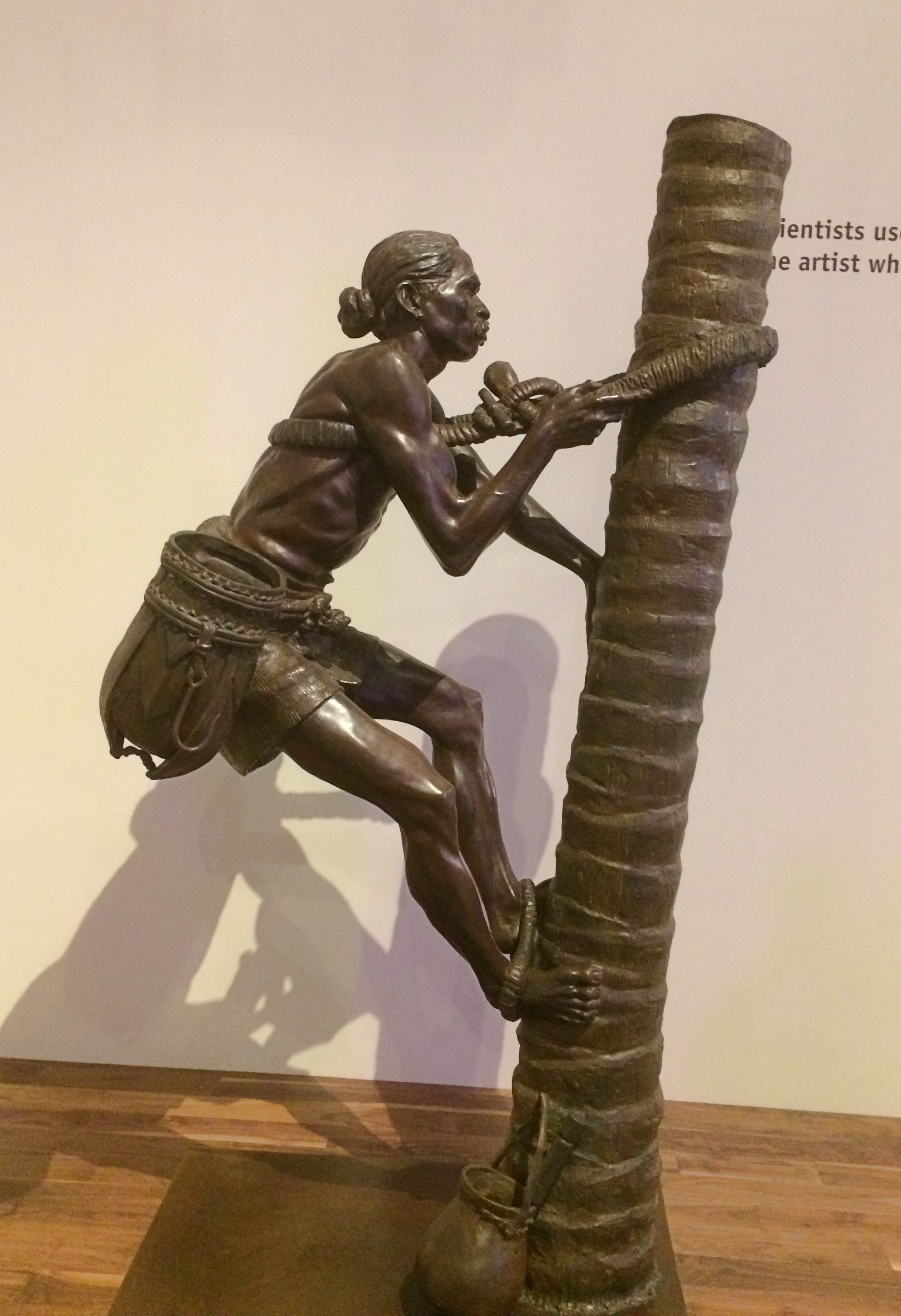

Here’s something you don’t see every day, which is pretty much the reason you go to a place like the Field.

We’d happened onto an exhibit called Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman. It’s a remarkable group of sculptures.

We’d happened onto an exhibit called Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman. It’s a remarkable group of sculptures.

“In the early 1930s, the Field Museum commissioned sculptor Malvina Hoffman to create bronze sculptures for an exhibition called The Races of Mankind,” the museum says. “Hoffman, who trained under Auguste Rodin, traveled to many parts of the world for an up-close look at the ‘racial types’ her sculptures were meant to portray.

“By the time the exhibition was deinstalled more than 30 years later, more than 10 million people had seen it — as well as its misguided message that human physical differences could be categorized into distinct ‘races.’

“Today, 50 of Hoffman’s sculptures are back on display — with a new narrative.”

Namely, that Hoffman did some remarkable sculptures of individuals, not illustrations of racial typologies. There’s some indication that Hoffman herself considered the whole typology idea as malarkey, even as she was creating the artwork.

“In her letters from the field, Hoffman told museum curators that she wanted to illustrate the dignity and individuality of each of her subjects,” the museum says.

“The Looking at Ourselves exhibition team believed that naming Hoffman’s previously unnamed subjects was an important way of illustrating that individuality. They spent months poring over Hoffman’s and her husband’s letters and journals, and consulting the work of others who have researched the Hoffman collection over the years, to find the subjects’ given names.

“For subjects whose specific identities remain unknown, the team worked with anthropologists to correctly pinpoint the names of their ethnic groups.”

The figure above, climbing a tree, is a Tamil man from southeast India, identity unknown. This is a Nuer man from Sudan, also unknown.

A group from various parts of Indonesia, put together by the artist. The two standing figures were modeled on Ni Polog and I Regog, a sister and brother from Bali. The others are a man from Madura and one from Borneo, identities unknown.

A group from various parts of Indonesia, put together by the artist. The two standing figures were modeled on Ni Polog and I Regog, a sister and brother from Bali. The others are a man from Madura and one from Borneo, identities unknown.

A Hawaiian: Sargent Kahanamoku, an aquatic athlete and member of a well-known Hawaiian family.

A Hawaiian: Sargent Kahanamoku, an aquatic athlete and member of a well-known Hawaiian family.

Glad we got to see Hoffman’s work. Ann and I spent a fair amount of time looking at them and discussing them. An idea for those who would destroy discredited statues: re-contexturalize instead.

Glad we got to see Hoffman’s work. Ann and I spent a fair amount of time looking at them and discussing them. An idea for those who would destroy discredited statues: re-contexturalize instead.