Not far from Manistique, Michigan, is the small Palm Book State Park, whose main attraction is known as Kitch-iti-kipi. It was last place we visited earlier this month in the Upper Peninsula, not long after enjoying a pasty and other good food for lunch at the Three Seasons Cafe in Manistique. This was a place I’d never been to, either.

The place is also called Big Spring. That’s what it is: big and astonishing clear, though it’s a little hard to tell from mere photos of the surface.

“About 10,000 gallons of water per minute gush into the lake from the fissures in the limestone that holds the pool,” notes Atlas Obscura. “Because its water is replenished so quickly, the pool maintains a constant temperature of 45 degrees Fahrenheit.

“It is unknown exactly where the enormous volume of water that fills the lake comes from. Tourists flock to Kitch-iti-kipi because it’s a geological wonder, and also because of the beautiful ancient tree trunks that are encrusted with minerals.”

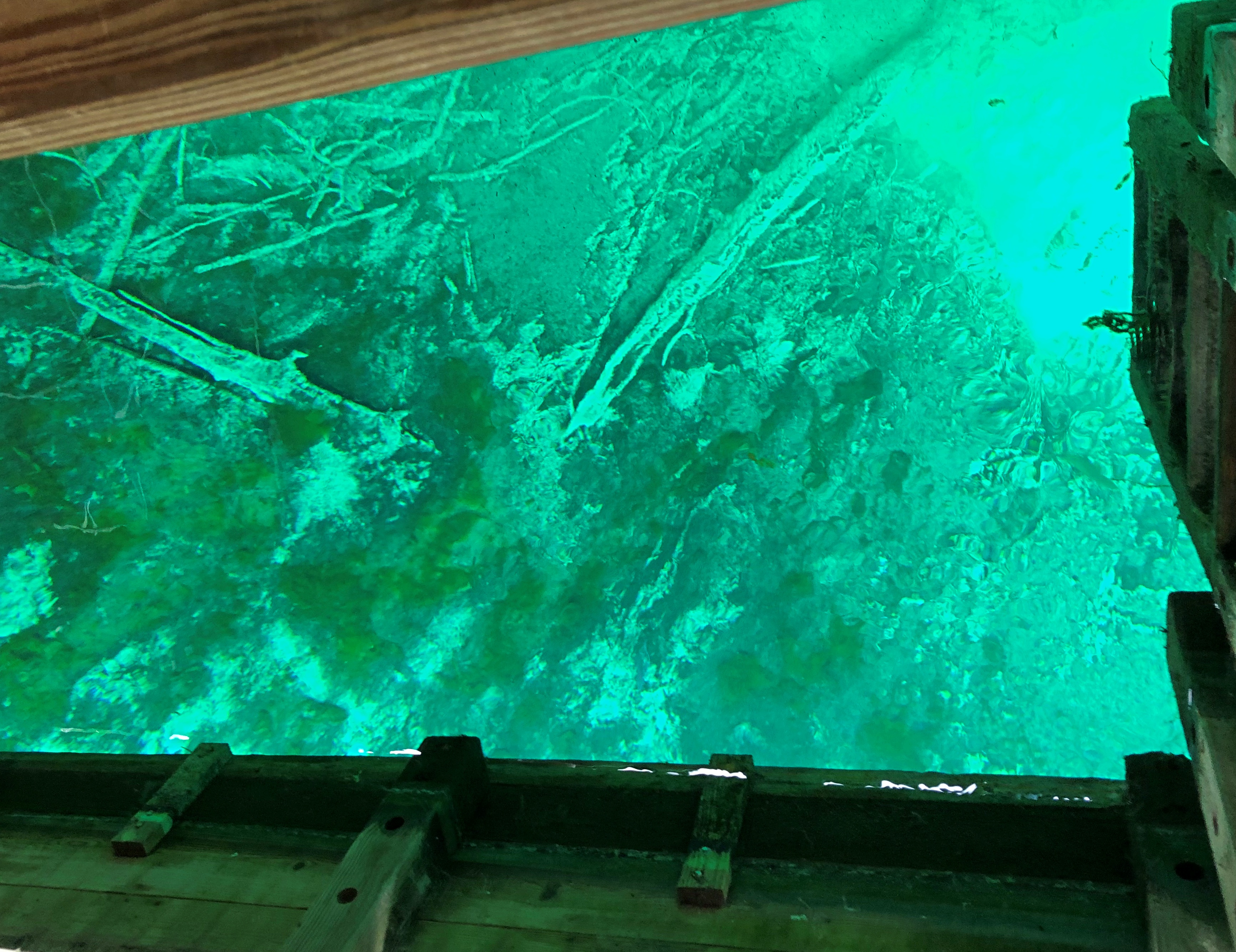

Images taken down into the spring are a bit different, but even then it’s hard to capture what the eyes do: a vivid reflection of the trees on the shore, a ghostly picture of the bottom, 40 feet down and tinted emerald, littered with logs and populated by fish.

Submerged wood closer to shore.

You don’t just stand around the edge of the pond, looking in. When you get near the spring, you get in line.

The line takes you to a dock where you wait your turn — it took us only about 15 minutes in line — to board an observation raft tethered to a cable.

The raft is moved across the pond, and back, by a single person turning a crank on board. Whoever volunteers to do so turns the crank, and kids seemed especially eager, since it didn’t seem to involve much muscle power at all. I’m not sure how that works, but it did.

The bottom of the pond is visible through the raft, since it’s in the shape of a square doughnut.

Online sources talk of the modern discovery of the spring about 100 years ago, and the Indian lore probably made up for the occasion, as discussed in this Michigan DNR video.

Another video, clearly made by a UP enthusiast, offers more geological information on how the spring came to be.