Remarkably, the election seems to have been anticlimactic. So far, anyway. Probably the best outcome to be hoped for, two sumo wrestlers huffing noisily to a draw. I did my little part, voting about two hours before the polls closed, because it had been a busy day at work, and every time I considered voting early during the last few weeks, I thought, nah.

Even more remarkably, we had lunch on the deck today. This evening at about 8, I sat out there in a light jacket under the waning moon and Jupiter high in the sky, and comfortably drank tea and ate a banana-flavored Choco Pie.

For anyone who’s interested, the International Olympic Committee created a report called “Over 125 years of Olympic venues: post-Games Use.” I can’t speak to the organization’s exact motives in producing such a document, but it seems to be a way to assert that most host cities weren’t stuck with too many white elephants after the Games.

Maybe so. The report notes that of the permanent venues used in both Summer and Winter Games from 1896 to 2018 — there were 817 all together — 85 percent are still in use. Many of those, if not most, already existed when the Games came to town, however.

Those 15 percent of unused venues are what tend to get attention. Or rather, a fraction of them.

“Of the 15 per cent of permanent venues not in use (124 venues), the majority (88 venues) were unbuilt or demolished for a variety of reasons,” the report says, using that charming British style for spelling out % and unbuilt as a verb.

“Some had reached the end of their life, some were destroyed during war periods or in accidents, while others were replaced by new urban development projects or were removed for lack of a business model. The remaining venues not in use are closed or abandoned (36 venues).”

Those last ones would be fodder for urban explorers and editorialists who want to discuss the deleterious impact of the Games on urban spaces. Tellingly, the report notes that Los Angeles isn’t going to build any new venues for ’28.

“The ‘radical reuse’ concept also applies to the training facilities and the Athletes’ Village,” it says.

Guess the IOC is going to have to live with the fact that cities are now hesitant to build spiffy new facilities that mostly benefit the IOC.

Here are photos of some of those abandoned sites. The ones that surprise me are the abandoned swimming pool and amphitheater from the ’36 Games. Sure, those were the Nazi Olympics, but the main stadium has been maintained by a more benevolent German government, why not the pool?

I took a look at that stadium — Olympiastadion — during a walkabout in West Berlin in 1983. That’s only one of two former Olympic sites that I can remember visiting. The other was a facility for the 1976 Montreal Games, the Centre Aquatique, where we went swimming in 2002.

I had these places in mind when I strolled through Centennial Olympic Park in downtown Atlanta. Its origins are on display.

The 21-acre park actually isn’t listed in the IOC report, because no sporting activity took place there. Rather, it was intended to be a gathering spot for visitors and spectators, and then a city park once the Games were over, and so it is. A pleasant place to wander on a warm weekend morning.

The park includes green space.

Some structures left over from ’96.

Sculpture from that same year.

“Tribute” by Greek artist Peter Calaboyias, depicting (right to left) an ancient Olympic athlete, a participant in the first modern Games in Athens in 1896, and an Atlanta Games participant.

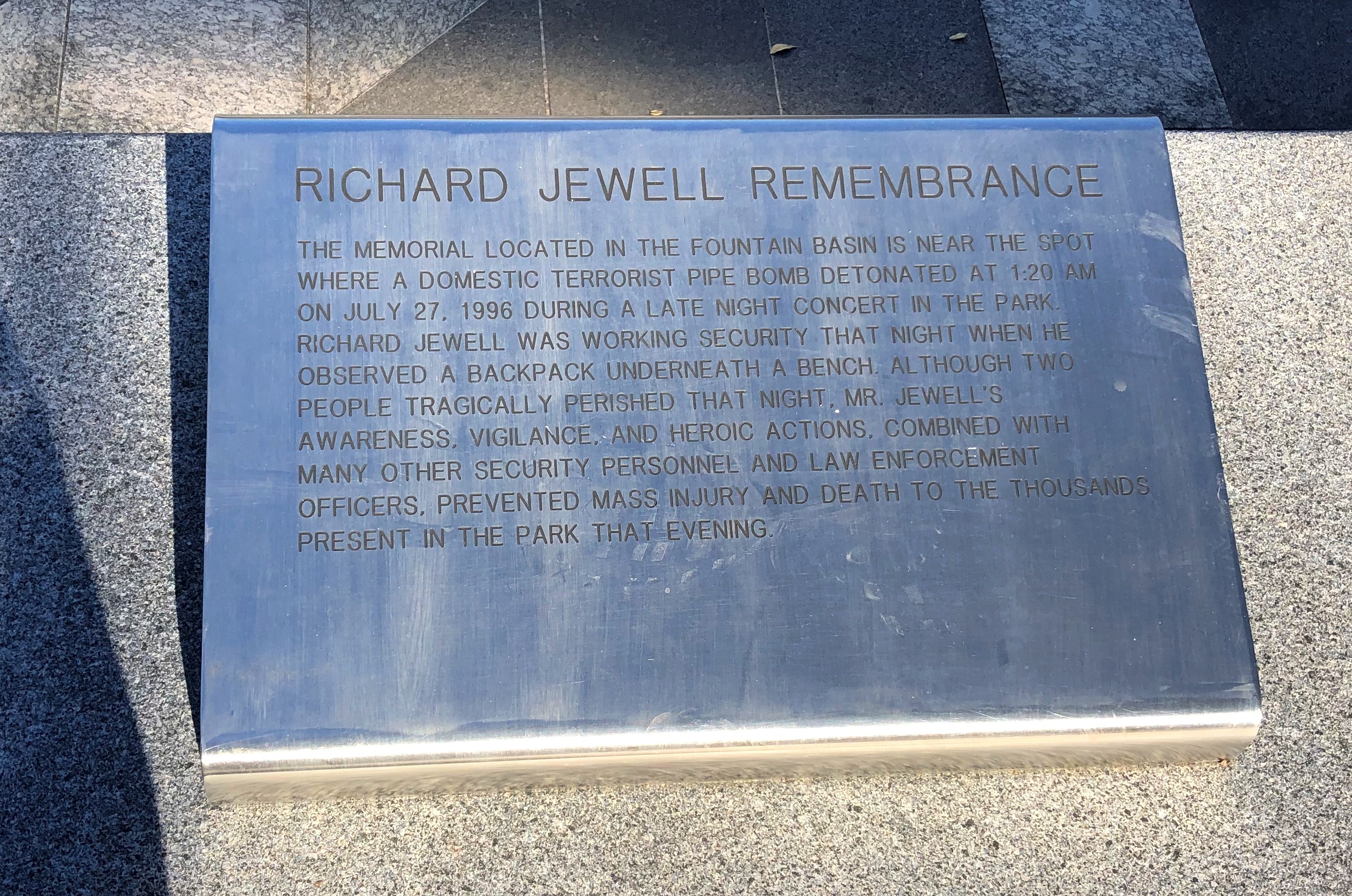

Poor old Richard Jewell has a memorial too.

Dedicated only in 2021. About time, I’d say.