At the corner of West Howard and North Main Street in Pontiac, Illinois, is an unassuming building.

The building itself didn’t catch my attention on Saturday morning before I ducked out of the numbing cold into the Route 66 museum across the street, nor did the glad fact that Pontiac still appeared to have a newspaper.

Rather, there seemed to be small murals on the walls. I went to take a closer look. Turns out they aren’t murals, but mosaics. Five all together.

They are part of the Daily Leader building, to go by the name on the wall. Except I have reason to believe that the paper, which is a Gannett asset, moved a few blocks away recently and a furniture retailer bought the building. That is what this item published by the Illinois Press Association says.

“For the first time since 1968, the Daily Leader has a new home,” the association reports. “As of Wednesday morning, July 13, the Leader office moved approximately four blocks to the northeast, to 512 N. Locust St. The Leader building on North Main Street was put up for sale earlier this year and purchased by Wright’s Furniture on May 13.

“The Pontiac Sentinel was begun as a weekly newspaper in 1857 and the Pontiac Weekly Leader arrived on the scene in 1880. In 1896, the weekly became a daily and the Daily Leader was born.”

One nit to pick: there’s no date on the item. You’d think that would be an important thing for an organization like the association to include, so I’ll assume it’s just an oversight. Happens to everyone.

But I do know it’s from this year, since July 13 was a Wednesday this year, and the story mentions 2019 as being in the past. Still, you shouldn’t have to rely on internal evidence to date a news story.

The mosaics taken together have a theme, the history of the graphic arts. This is the first of the mosaics as they proceed chronologically around the building’s two street-facing walls, beginning with cave dwellers and their art.

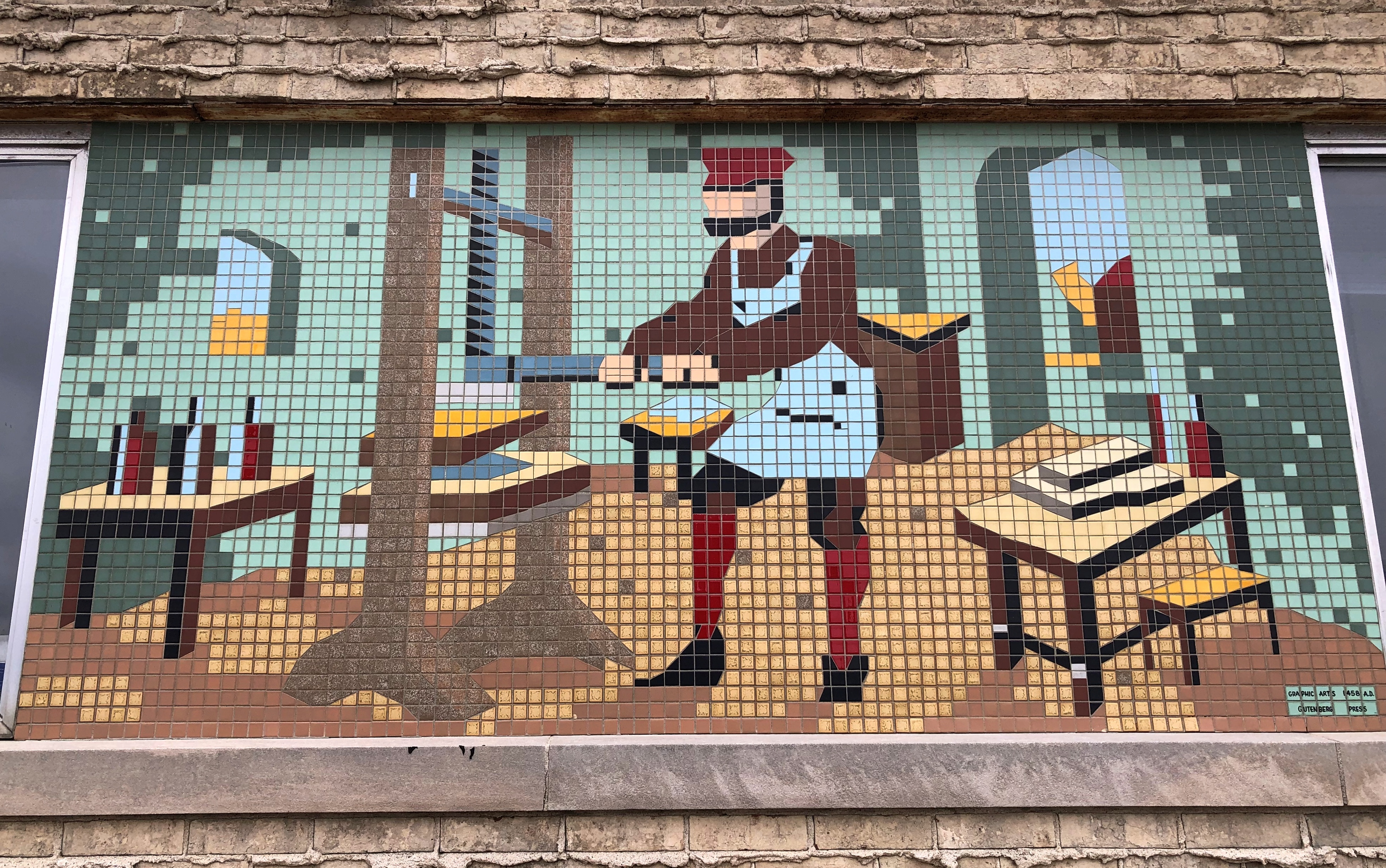

Ceramic tiles (tesserae) were put in fully regular x-y grids form the images, though within many of the squares, irregular shapes are cut to fit each other, as long as it serves the purpose of creating the overall image. The more I look at the mosaics here in the warmth of my office, the more I like them.

Next, the scribes of ancient Egypt.

Each mosaic has a caption at the bottom. This one, for example, says:

Graphic Arts 2000 B.C.

Egyptian Hieroglyphics

Notice the detail. Seems simple, until you spend time looking at it. A lamp with candles hangs overhead; shadows lie more-or-less believably around the room; his hair is short but unkempt; the sandals are well depicted; the quill has a pleasing wave; the base of the desk and the bench are in matching dark colors; the top of the desk and paper, along with the contents of the box the right — scrolls? — are in matching light colors; the door is an oddly large part of the image, until you realize it leads the viewer past bushes and a tree to a building with a pointed window, like the room’s window. I can’t help but think that’s a church window.

Next, Gutenberg is making printing by hand obsolete.

The end mosaic, which is on the north face of the building, is longer than the others. This is a detail. It depicts the modern newspaper office. Modern, as in 1970.

I assume that date can stand in for the year the art was created. Let’s say ca. 1970, since I didn’t see a date or an artist’s name, though I didn’t inspect every inch of the mosaics as the wind blew the only direction it blows in winter — in my face.

I never worked for a newspaper professionally, but the characters remind me of the first jobs I had working for paper magazine publishers. To the right, a reporter making notes and another taking photos. Yet another reporter makes a phone call.

The news is thus gathered and then prepared for the press. I like to think the woman at the typewriter is a reporter too — women were entering the ranks of journalism in numbers by 1970, like in other professions — but she might have been intended as a typist.

From there, the text goes to a human typesetter. At my first writing job in Nashville in the mid-80s, we had two typesetters, youngish women back in their own room, though the editors consulted with them often enough about the text. They could be fun, smoking their cigarettes and accumulating coffee cups on nearby flat surfaces and bantering with the staff when they weren’t otherwise fixated on their jobs, which involved screen concentration and flying fingers.

At my next job, the typesetting job was automated by a typesetting program simple enough even for me to use, and I never again worked with human typesetters.

After the typesetter, who had created long strips of glossy paper with text — galleys — the layout man took over, waxing the backs of the galleys and placing them on thin cardboard sheets to create mocked-up pages, which in turn would be photographed for the presses. Man, I haven’t thought about the process in years.

At my second job, the layout man was old, opinionated, and sometimes prickly, having seen and (more likely) heard enough working with Chicago journalists to harden his character. There was a hint of cynicism in everything he said, and often enough much more than a hint. He was probably smarter than he let on. He didn’t smoke and had contempt for those who did. I suspect he drank and had contempt for those who didn’t. After my time, I understand he took retirement, and was replaced by computer programs.

All in all, the mosaics were quite a find on a casual walk. But that’s why I take them.