I might be misremembering, but I believe the Uffizi Gallery had a hallway that featured busts of every Roman emperor, plus a good many of their wives, down at least to Severus Alexander (d. AD 235), in chronological order. I spent a while there, looking over them all.

The Uffizi array included famed and long-lasting rulers (e.g., Augustus) but also obscure short-timers whose biographies tend to end with “assassinated by…” (e.g., Didius Julianus (d. AD 193), the rich mope who bought the office from the highly untrustworthy Praetorian Guard and held it for all of 66 days in 193).

I thought of all those emperor busts when I took a look at Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius on Saturday.

Second century AD, no doubt part of what would later be called propaganda: the effort to let the Roman people feel the presence of their rulers. These two busts are among the ancient Roman artworks on display at the Art Institute of Chicago, along with works by Greek, Egyptian and other peoples.

It isn’t a huge collection, though sizable enough. If you put together the ancient art found at Art Institute and the Field Museum and the Oriental Institute Museum, that might be a British Museum- or Pergamon Museum-class collection, but no matter. I always enjoy strolling around the Art Institute’s ancient gallery, which is back a fair ways from the main entrance, in four rooms surrounding a peristyle-like courtyard, though that is a story down.

Besides emperors, you’ll see emperor-adjacent figures, such as Antinous, done up as Osiris, 2nd century AD of course.

Beloved by Hadrian, Antinous took a swim in the Nile one day in AD 130 and drowned. Hadrian founded the nearby city of Antinoupolis in his honor (it’s a minor ruin these days) and proclaimed him a god — the sort of thing a grieving emperor could do in those days.

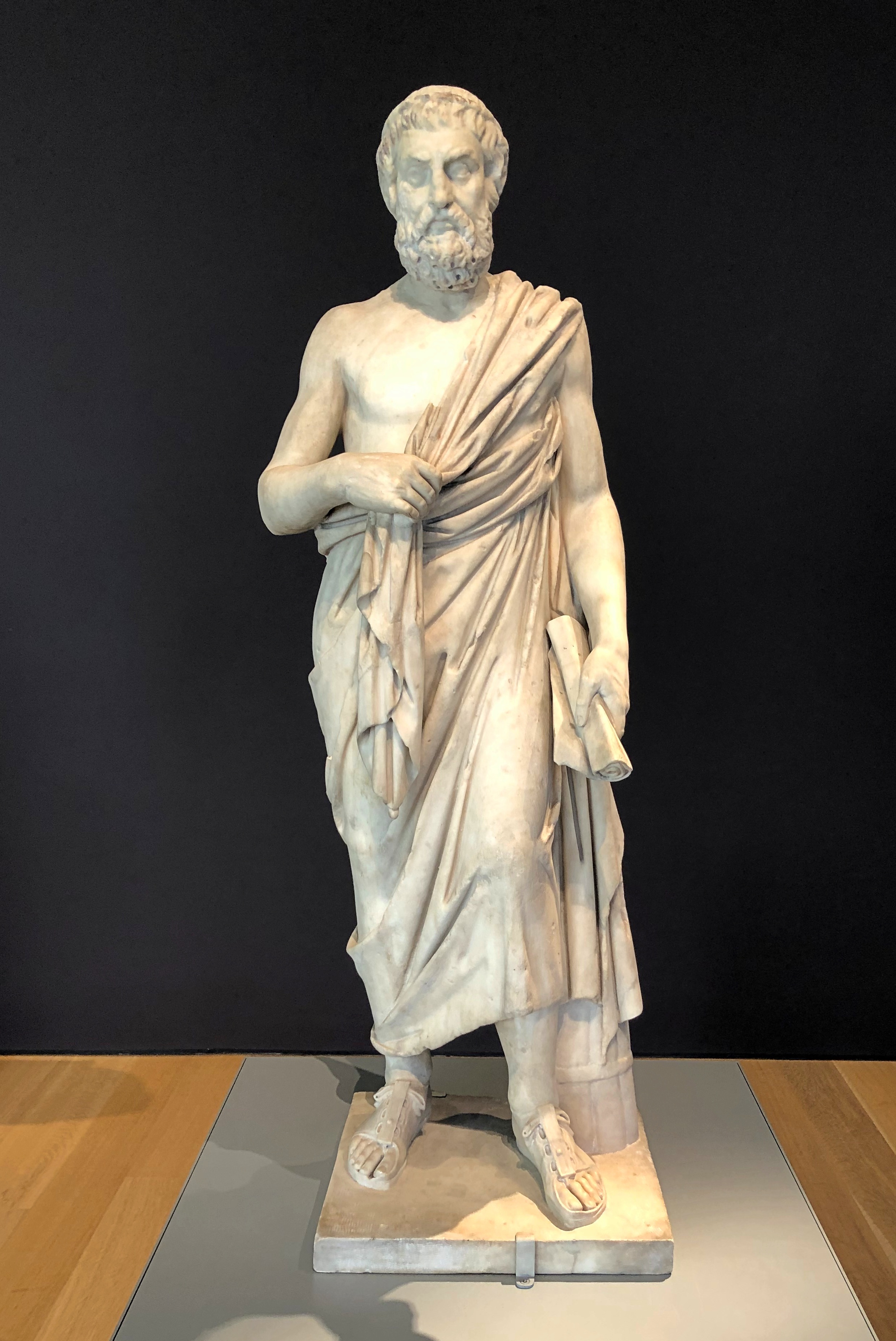

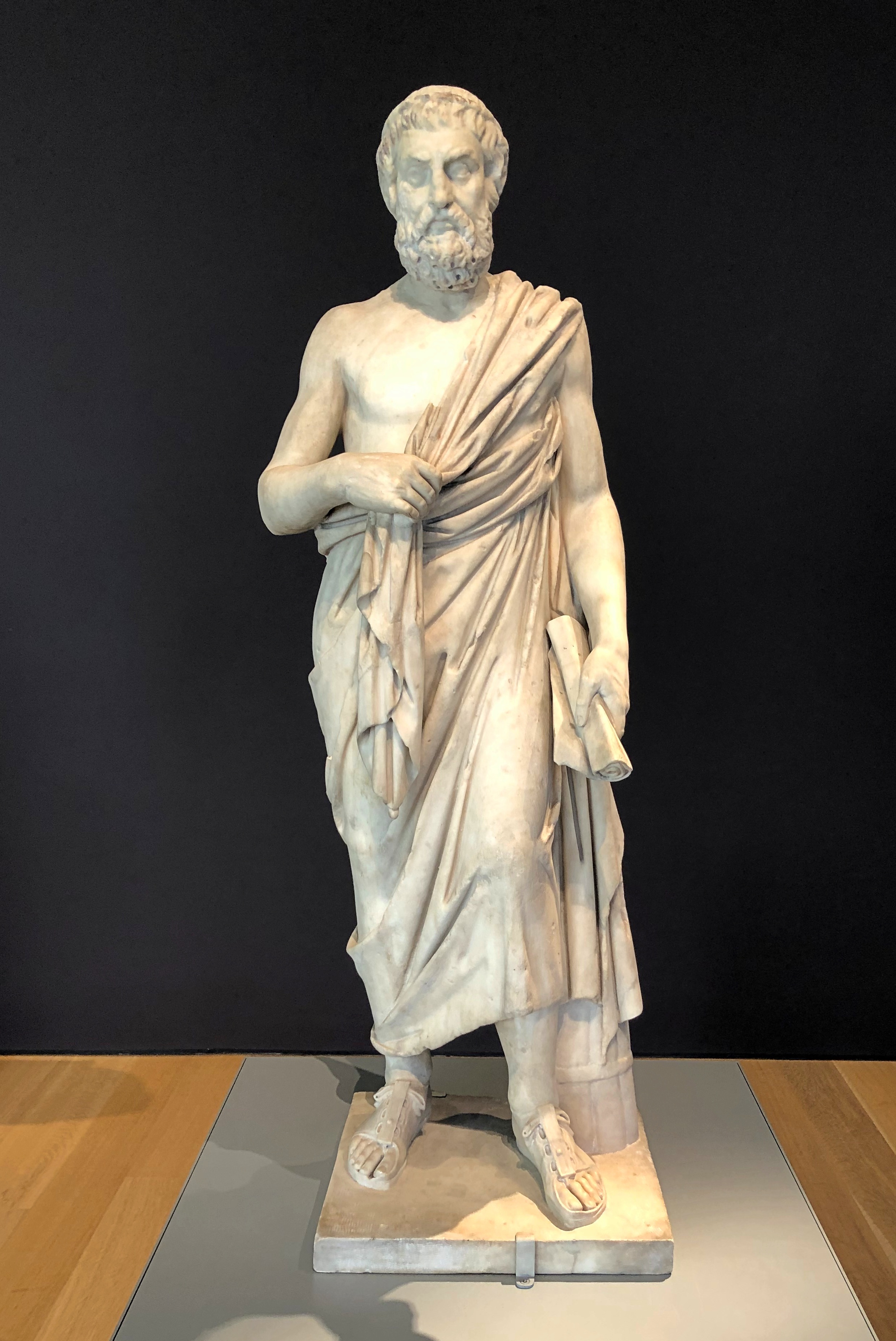

A Roman copy of a Greek statue of Sophocles, ca. AD 100.

Hercules, 1st century AD.

My cohort learned of Hercules through cartoons. Could have done worse, I guess.

A story never animated for children, as far as I know: Leda and the Swan, 1st or 2nd century AD. A story that nevertheless reverberates down the centuries.

Who doesn’t like ancient mosaics? I like to think these 2nd-century AD works were part of an ancient tavern that served food.

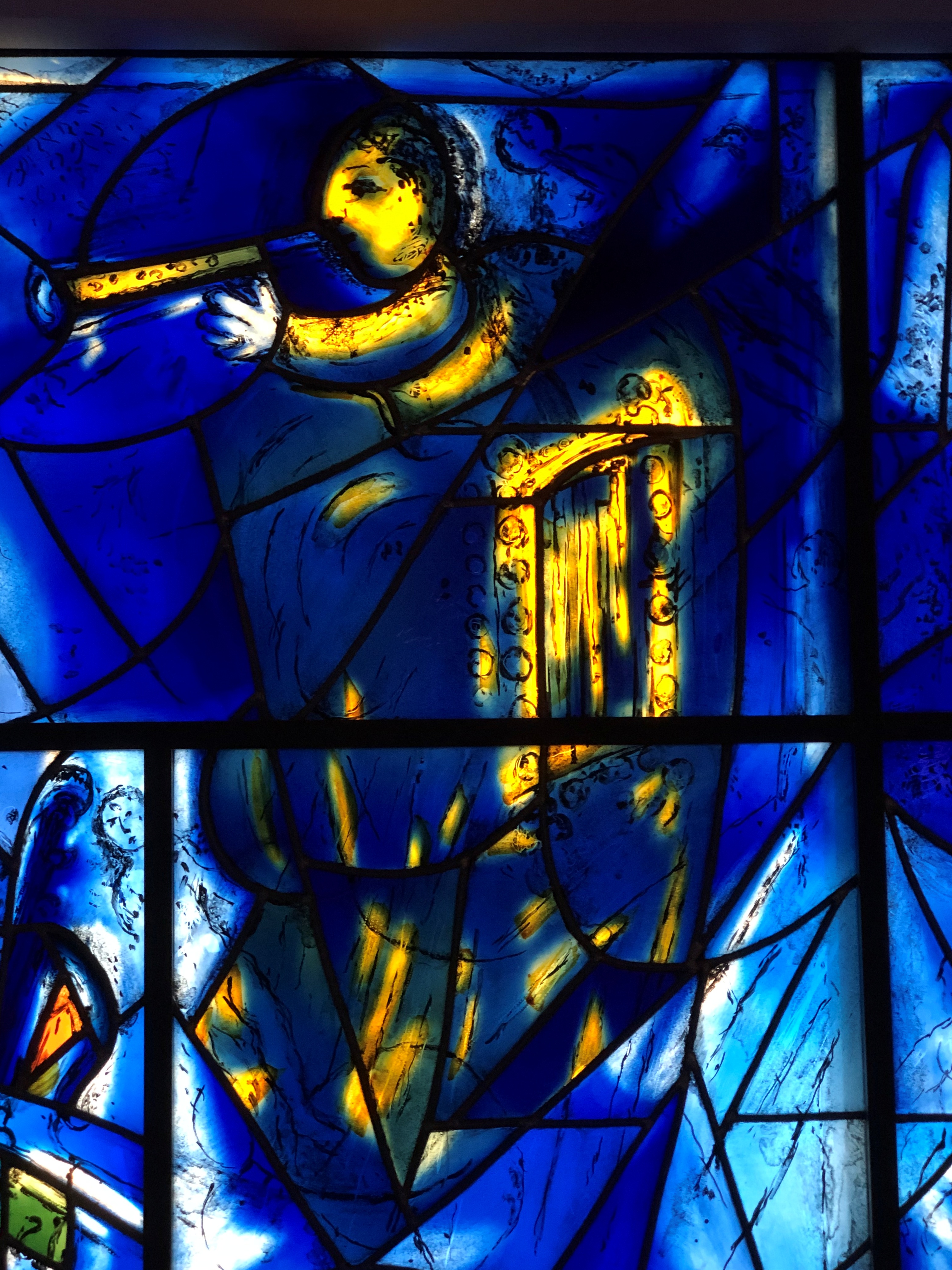

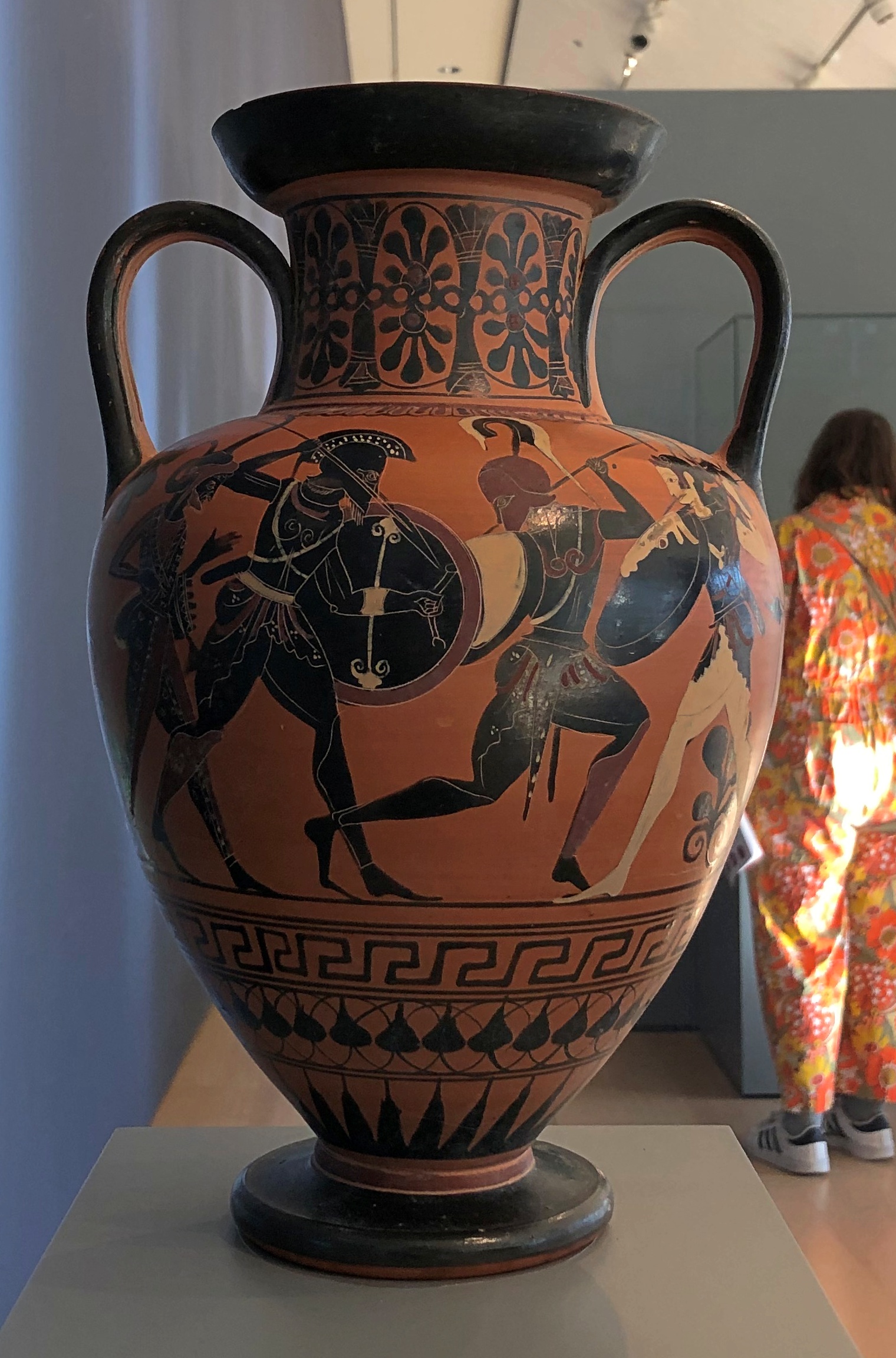

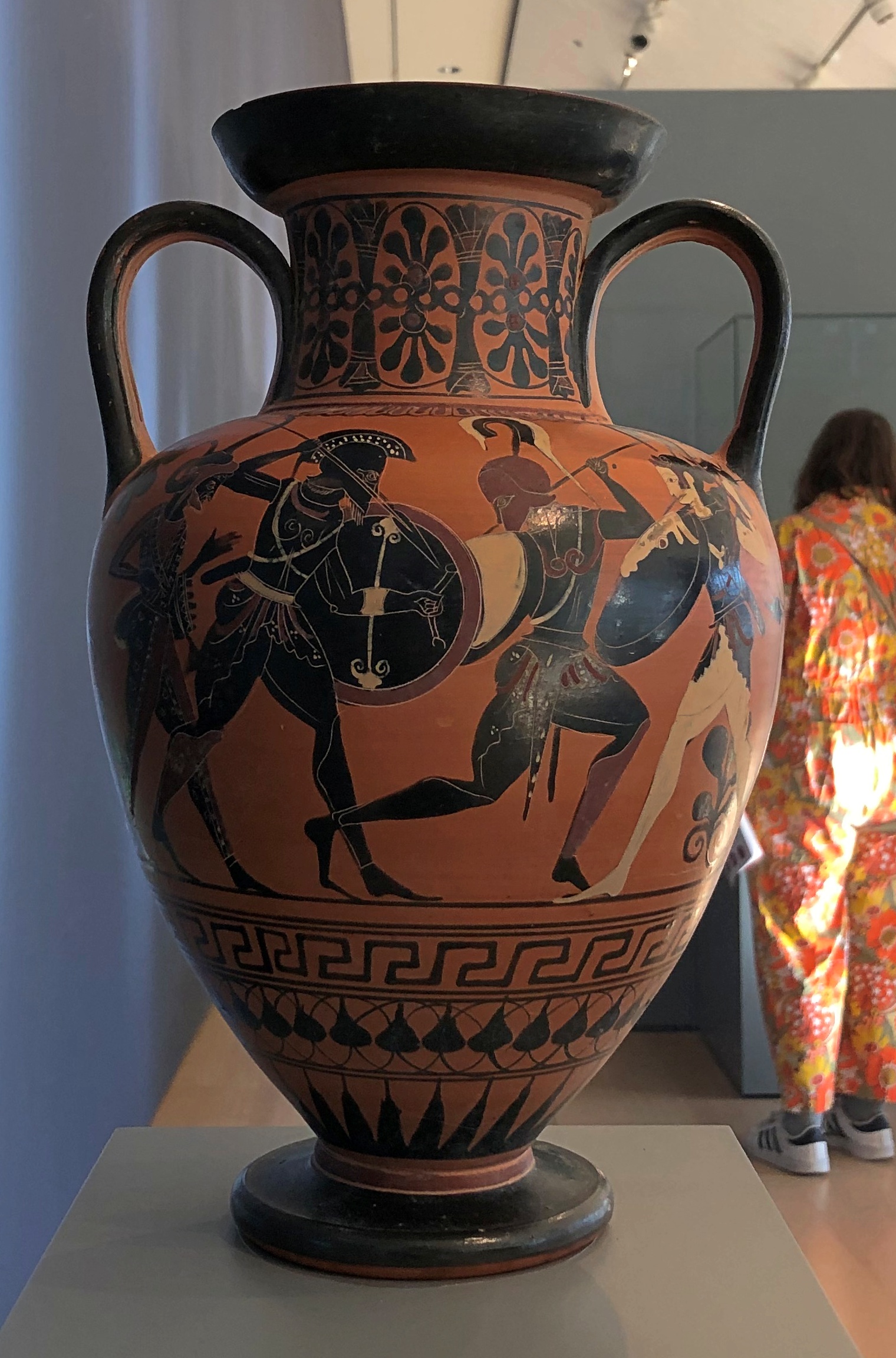

A sampling of Greek vases are on display as well. These black-figure works are from the sixth century BC, probably for storing wine. In vino veritas, though in this case that would be Ἐν οἴνῳ ἀλήθεια (En oinō alētheia), and I won’t pretend I didn’t have to look that up.

I always visit the coin case. Here’s a silver tetradrachm minted in the 2nd century BC in Asia Minor, depicting Apollo. Such detailed work for something struck by hand.

Then there’s this — creature.

Statue of a Young Satyr Wearing a Theater Mask of Silenus, ca. 1st century AD, the museum sign says (and he’s putting his hand through the mask). You need to watch out for those young satyrs. They’re always up to something.