I walked about a quarter-mile from a parking lot to get to the reconstructed log palisade on the site of one hastily built by men under the command of Lt. Col. George Washington, age 22. Fort Necessity, he called it. These days, the site is called Fort Necessity National Battlefield.

It is the only battlefield associated with the French and Indian War preserved by the National Park Service.

By the time I got there, I’d worked myself into a counterfactual frame of mind. Just what didn’t happen here — that easily could have – that proved so important for the future course of events in North America? Affected the fate of the unborn United States in unknowable but profound ways?

Those are the kind of Big Thoughts you get alone, under a pleasant late afternoon sun, in a meadow amid the rolling hills of rural southwest Pennsylvania, with nothing but a paved footpath and the palisade ahead. I do, anyway.

Consider: Washington and his men had surprise-attacked a French force at nearby Jomonville Glen a few weeks before the battle at Fort Necessity, defeating them and resulting in the death the French commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. Washington was well aware that the French weren’t going to let that incident go unanswered, so he ordered the completion of Fort Necessity to prepare for the counterattack.

Louis Coulon de Villiers, who was Joseph’s brother, led the French response and besieged Fort Necessity from an advantageous position and with a larger force. Many British — mostly members of the Virginia Militia — were cut down, dying in the mud from recent rain. It seems likely that the French could have killed most, if not all of Washington’s command, but Coulon asked for parley and ultimately gave Washington generous surrender terms. Essentially, get out of here, and promise not to come back for a while.

Would a man of a different temperament more aggressively ground the British to defeat, perhaps to the point of seeing its commander dead with his men? Washington, that is. Dead at 22. You can see how this line of thinking puts some counterfactual ideas in your head.

What motivated Louis Coulon to do what he did? Motive’s a hard thing to pin down even in someone alive today, much less a French military commander of the 18th century. From what I’ve read, he was under orders not to massacre the British, and his men were tired and low on ammunition even though the defenders of Fort Necessity were in much worse shape. Those seem like fairly compelling reasons. Still, a more aggressive or ruthless commander could have continued the fight, not really held back in the wilderness by mere orders. This was the force that had killed his brother, after all.

On the other hand, young Washington had a number of near-death experiences as he was surveying in the Ohio Valley before the war. What’s one more?

So many questions. Big history pivoting on small fulcrums. I got closer.

The site isn’t just that. Worn earthworks linger nearby.

Maybe Coulon was intensely proud to be under French arms, which were magnificently powerful in those days, even at such a far-flung place, and wasn’t about to dishonor his command with a massacre. Or maybe he didn’t like his brother that much, and was inclined to be philosophical about his fate. C’est la guerre, dear brother.

Down the road from Fort Necessity, U.S. 40 that is, is the grave of Major Gen. Edward Braddock.

I won’t go into details about why he’s there, except that it’s only indirectly related to the battle of Fort Necessity. He’d been sent with a much larger British force to confront the French the year after that battle. Things didn’t go well for him, and he ended up buried under the military road he had had built as part of his campaign to take the Ohio Valley from the French.

The wooden beams mark the course of the road.

The monument was erected in the early 20th century. He’s probably under it, but we can’t quite be certain.

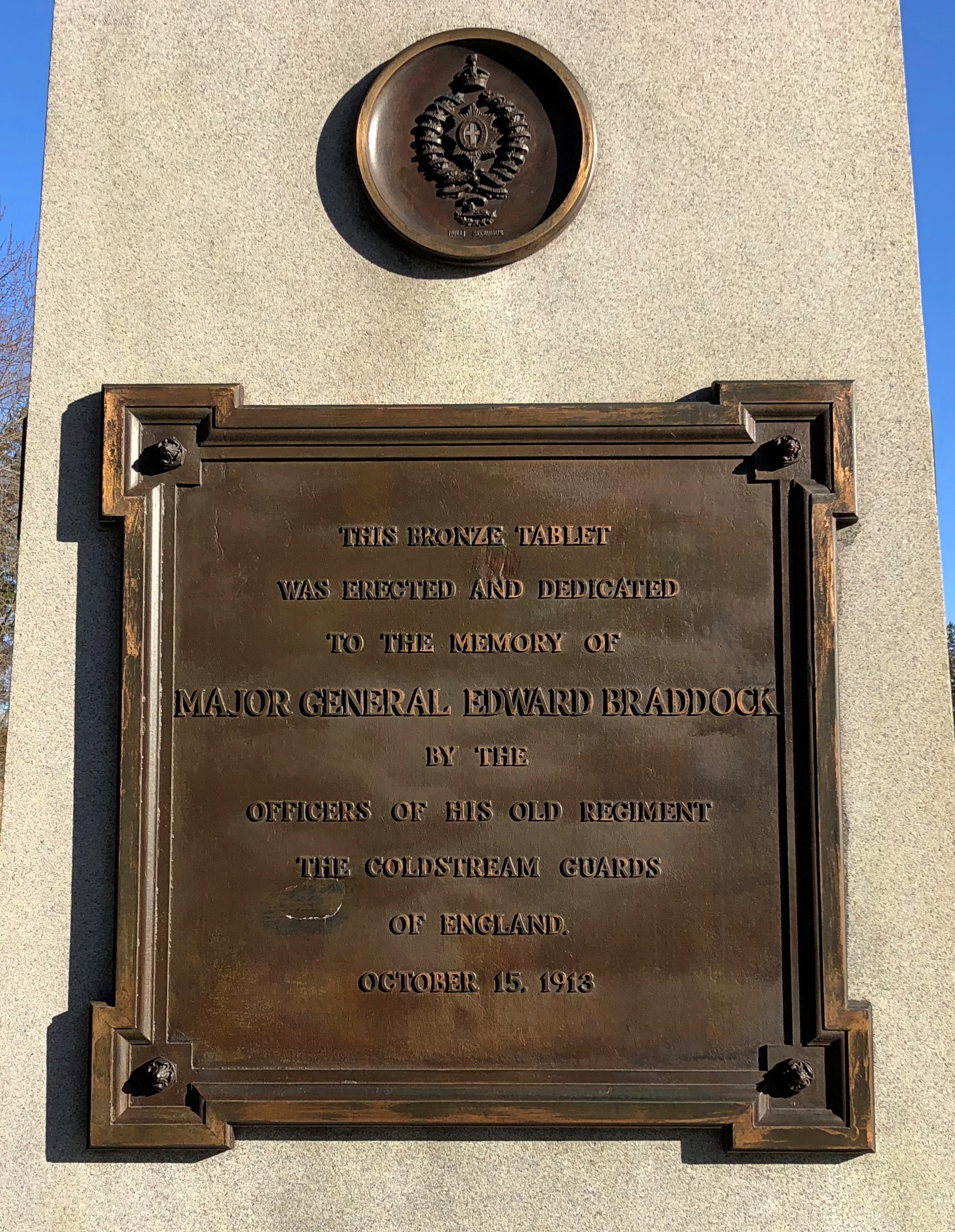

This plaque adds an extra layer of poignancy.

Nineteen-thirteen. It’s probably just as well that the officers of the Coldstream Guards didn’t know what was coming.