We arrived at Quapaw Baths in Hot Springs National Park on April 14 in time for a late-afternoon soak.

Or rather, a series of soaks in its indoor pools, which are heated at various temperatures. I might have skipped it, but Yuriko is keen on hot soaks, having come of age in Japan, where they take their hot springs seriously. The bathhouse has been well well restored, considering its former decrepitude.

Good to see Bathhouse Row again after so many years. All together, eight bathhouse structures line Central Avenue in the town of Hot Springs, and are part of the national park; two offer baths. In 2007, because the Quapaw was still unrestored, only one did, so we took the waters at the Buckstaff, which was a more formalized experience than at the Quapaw.

“[The Lamar] opened on April 16, 1923 replacing a wooden Victorian structure named in honor of the former U. S. Supreme Court Justice Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar,” says the NPS, a fact that amuses me greatly, for idiosyncratic reasons. Mostly it’s NPS offices and other space these days, but I bought some postcards and a refrigerator magnet in its NP gift shop.

And of course, The Fordyce, now the park’s visitors center and a free museum highlighting its bathhouse amenities. Named for its founder, Samuel Fordyce, one of those roaringly successful business men that the late 19th century unleashed.

“He was a major force behind the transformation of Hot Springs (Garland County) from a small village to major health resort,” the Encyclopedia of Arkansas says. “The town of Fordyce (Dallas County) is named for him, as is the Fordyce Bath House in Hot Springs.

“He enjoyed friendships with Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley, all of whom asked his advice on matters concerning appointments and regional issues.” Ah, there’s the trip’s presidential site, however tenuous.

As for the building, it was “designed by Little Rock architects Mann and Stern and constructed under the supervision of owner Sam Fordyce’s son John, [and] the building eventually cost over $212,000 to build, equip, and furnish.” That’s 212 grand in fat 1910s dollars, or $6.5 million in present value.

I believe I took somewhat better pictures this time around. Maybe.

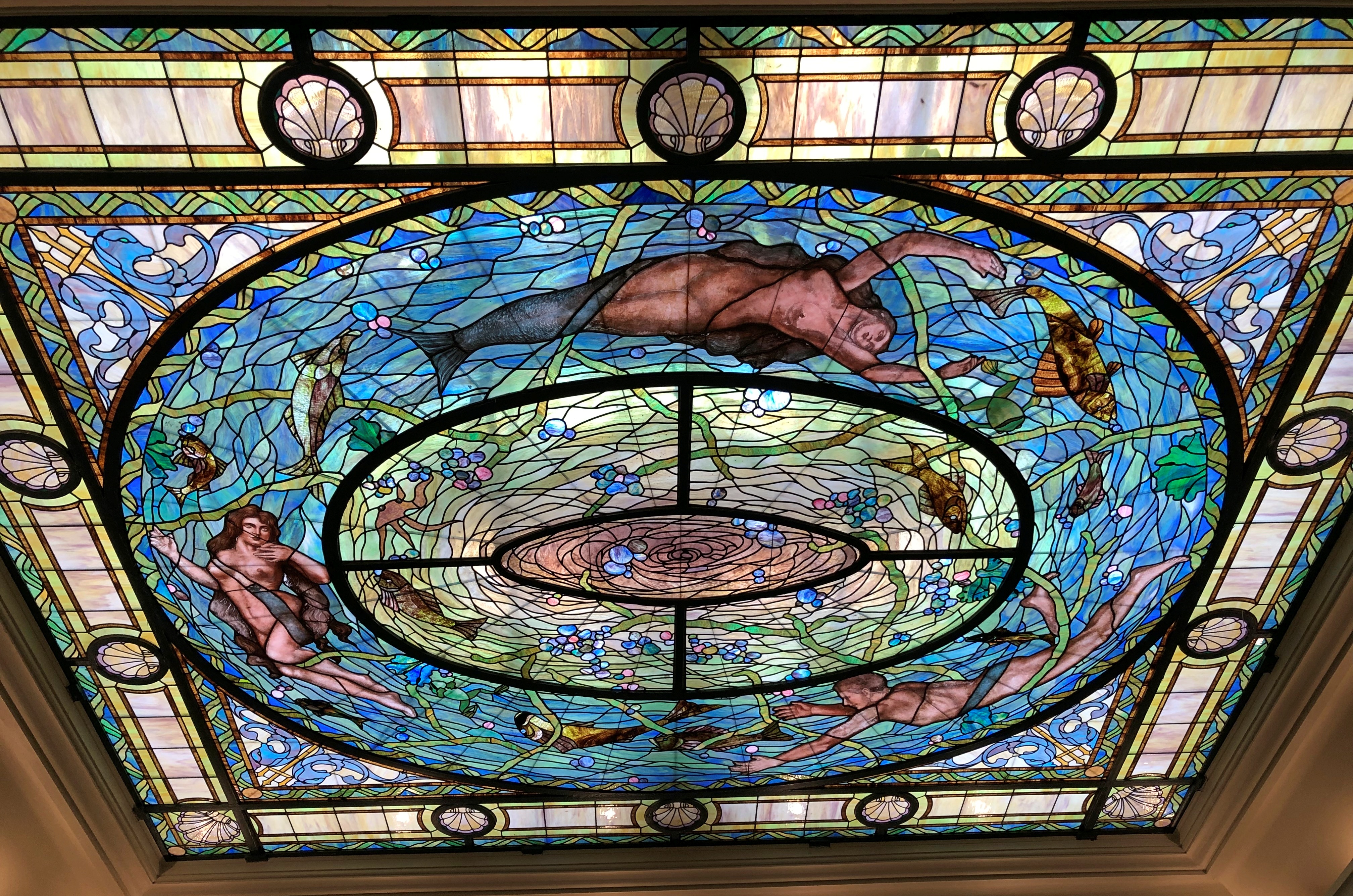

Directly over Hernando de Soto and the maiden is the Fordyce’s famed stained glass aquatic-fantasy skylight.

Not the only stained glass around.

The Fordyce is an expansive place, and in fact, the largest of the bathhouses, according to the NPS.

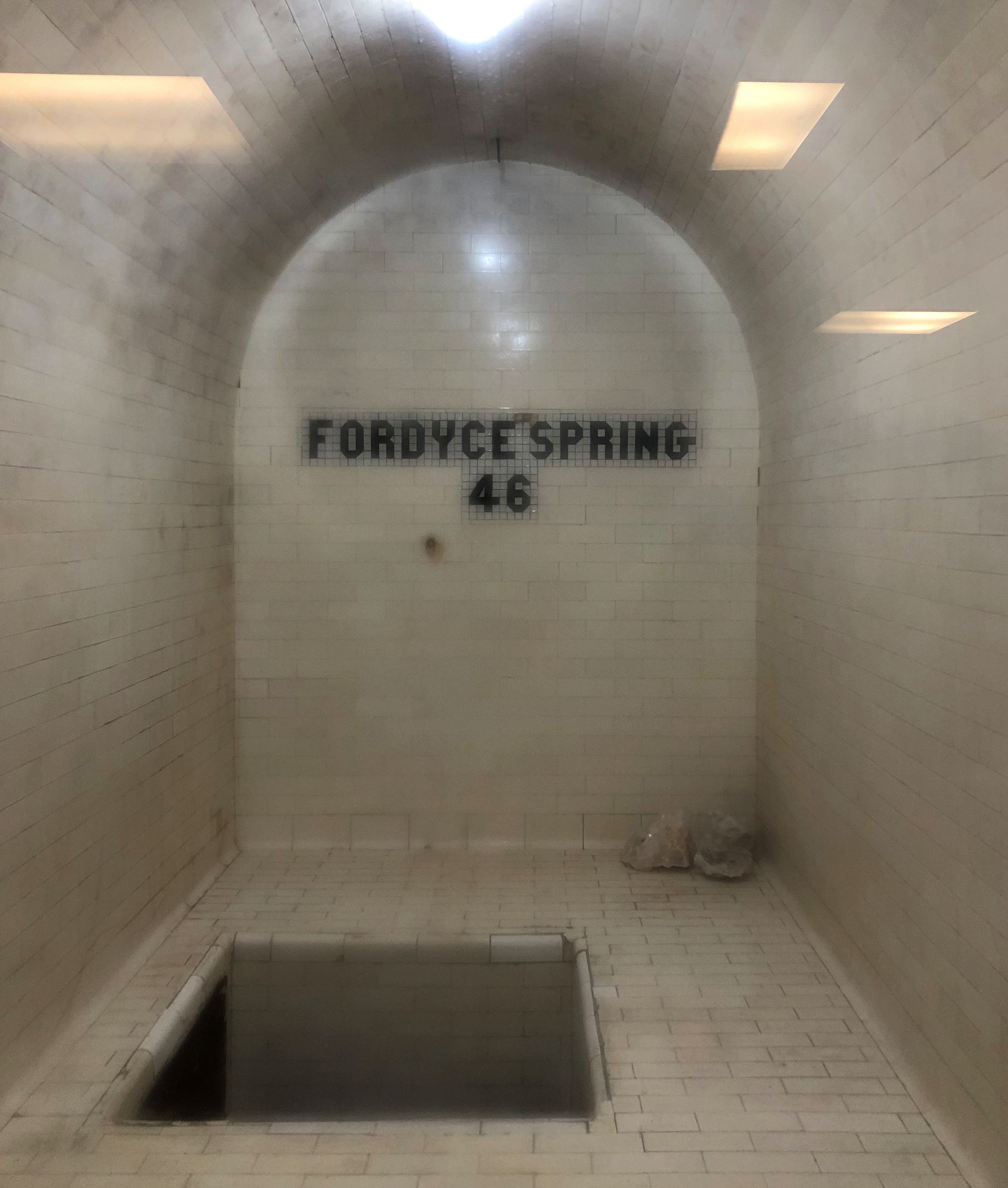

Mustn’t forget the spring that made it all possible, whose presence is noted in the basement.

Bathhouse Row is at the base of a steep slope. Climb some outdoor stairs and soon you’re at the Hot Springs Grand Promenade behind and above the row. Not many people were out promenading. True, by the time we got there, it was the morning of April 15, a Monday. Still, people were missing out on one pleasant walk.

The bricked trail was an early project (1933) of the lesser-known but no less remarkable Public Works Administration.

“Unlike the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration, the PWA was not devoted to the direct hiring of the unemployed,” the Living New Deal says. “Instead, it administered loans and grants to state and local governments, which then hired private contractors to do the work.

“Some prominent PWA-funded projects are New York’s Triborough Bridge, Grand Coulee Dam, the San Francisco Mint, Reagan National Airport (formerly Washington National), and Key West’s Overseas Highway.”

Further up the hill is the abandoned Army Navy Hospital, whose therapeutic heyday was WWII.

The promenade passes by some of Hot Springs’ hot springs.

The path also offers views of the back of some of the bathhouses, including the wonderful Quapaw dome.

The crowning bit (literally) on a marvelous piece of work.