If the Belém Tower and the Monument of the Discoveries were about Portuguese ventures into the world, the nearby Jerónimos Monastery shows one thing they brought back: immense wealth. Taxes needed to be paid on the incoming wealth, of course, and a certain large part of those levies went to build Mosteiro dos Jerónimos. The Hieronymite monks who lived there for a few centuries were tasked to pray for the souls of successive kings of Portugal and to minister to those leaving on ocean-spanning voyages.

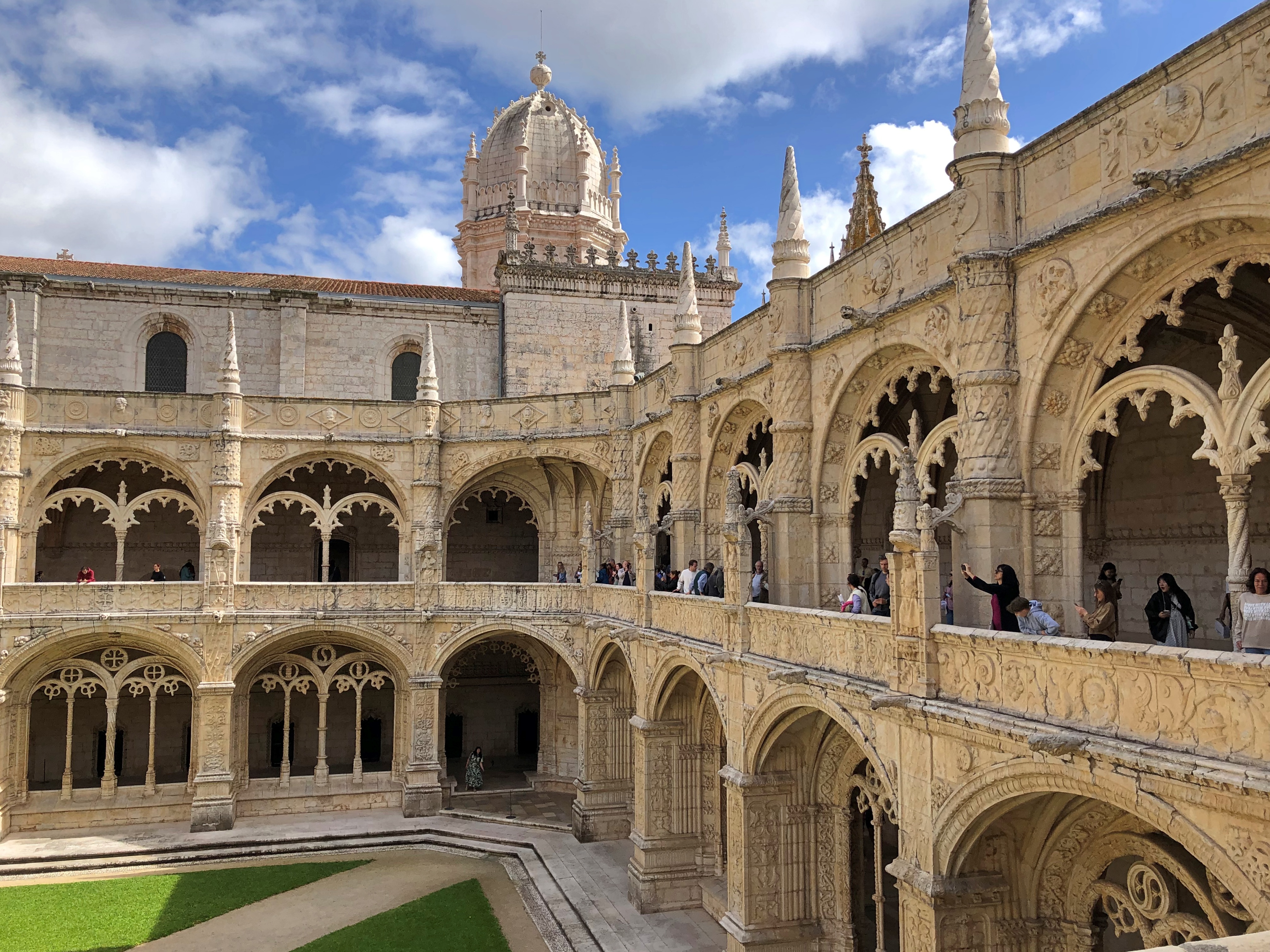

Money well spent, I’d say. The monastery is the extraordinary work of a number of hands, beginning with architect Diogo de Boitaca and including a succession of other architects, designers and sculptors. Together with Belém Tower, it is a World Heritage Site.

The outside of the monastery church, Santa Maria.

The monastery grounds include other large museums, such as ones devoted to Portuguese naval history, and an archaeological museum, both of which would surely be worth the time. But we focused, as most visitors do, on the monastery church and the cloister next to it.

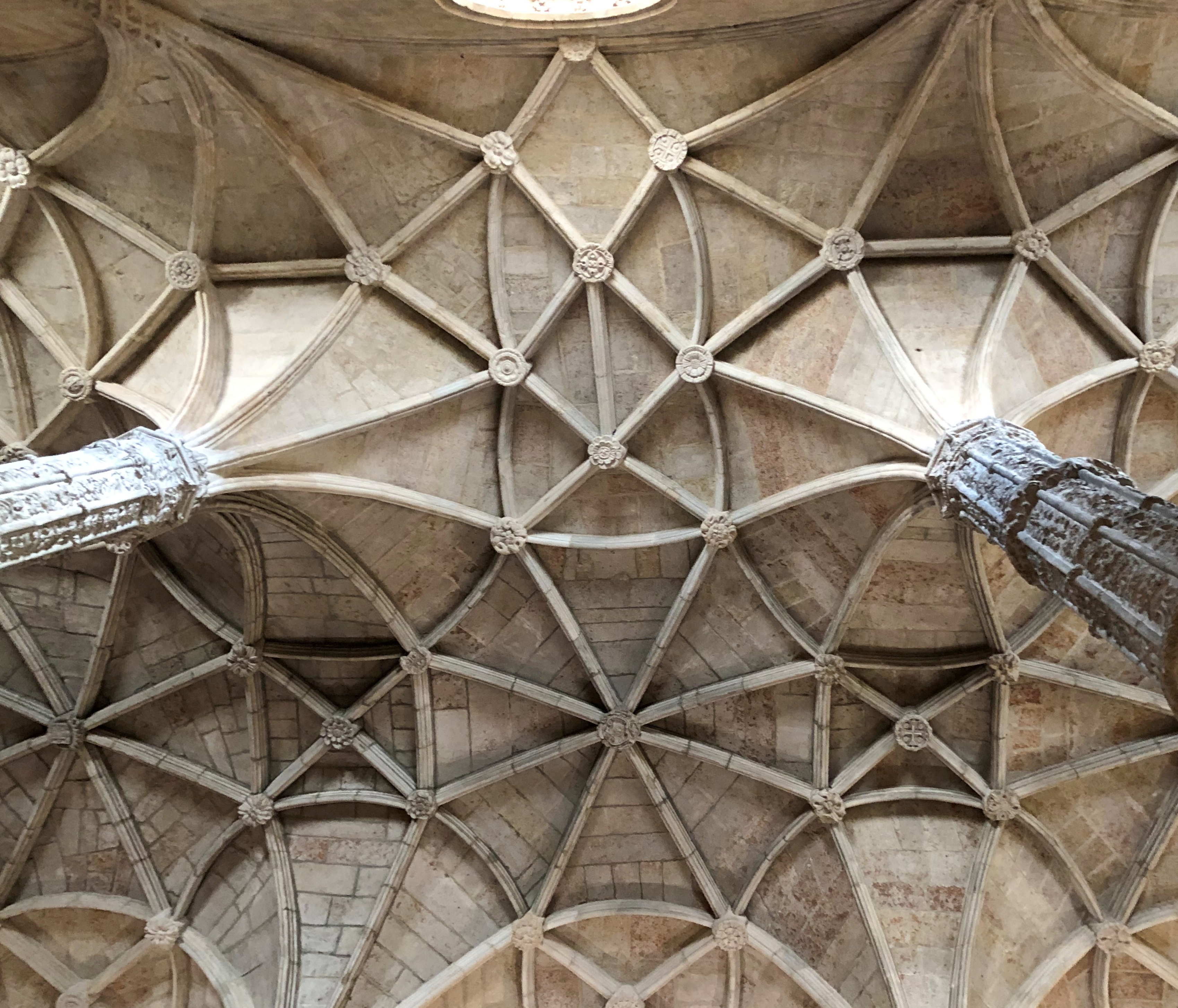

These structures are considered class-A examples of Manueline, a style particular to Portugal during the Age of Discovery and with an emphasis on elaborate stonework. Sturdy work, too: the earthquake of ’55 didn’t do a lot of damage to the monastery.

Some Portuguese royals, namely the go-getters of the Aviz dynasty who oversaw worldwide Portuguese expansion, are entombed in both transept chapels. Note the elephants supporting the tombs.

Vasco da Gama, as mentioned previously, has a tomb near the church’s entrance. Across from him is the Portuguese epic poet Luís Vaz de Camões (d. 1580), whose best known work celebrates the voyages of da Gama.

The poet might not actually be in the tomb. His original resting place was disturbed by the 1755 earthquake, and by the time of his entombment in Santa Maria in the 19th century, finding his remains was a matter of guesswork.

Santa Maria church, I’m glad to say, charged no admission, though I was happy to donate a few euros to its upkeep. All you have to do is wait in line, which took about 20 minutes.

The cloister, on the other hand, sold admissions, though at a fairly reasonable 10 euros. It was busy, but not so crowded that we couldn’t buy admission right then. Anyway, it was entirely worth it.

One is allowed to peer into the courtyard, but not enter it. I believe that that’s actual grass, not Astroturf.

Endless details carved all around.

A large refectory includes the sort of tilework that Portugal is famous for.

Including a depiction of an emotionally distressed horse.

That’s what it looks like to me, at least. Some of the tile artists apparently appreciated the fact that such a horse’s lot is little but work, work, work.