Sounds of the northwest suburbs in the seconds after midnight, New Year’s Day 2025.

A little way down our block, a knot of school-aged kids were in a front yard just after midnight, yelping and whooping and tooting horns as the fireworks popped all around the neighborhood; you can hear them on the third recording. The father of the house stood in the front door, up a few steps. Soon the kids headed up the steps to go inside, and I noticed gold-colored crowns on all of their heads, including the dad.

On the Monday before Christmas, we found our way to Kokomo Opalescent Glass Co., which is housed in an unpretentious complex in an unpretentious neighborhood in that town.

It’s another legacy of the Kokomo Gas Boom. A French glass chemist named Charles Henry found his way to Kokomo in the late 1880s, taking advantage of free natural gas to set up a glassmaking factory. That arrangement didn’t last, since Henry was more a technical man than a manager, and a heavy drinker besides, so he lost the factory and thus didn’t become the glass baron of Kokomo. But under other management the company has endured. KOG abides, you could say.

Three of the maw-of-hell furnaces for melting glass. There were others.

“Founded in 1888, KOG is the oldest producer of hand cast, cathedral and opalescent glass in the United States… known worldwide for our high-quality, hand-mixed sheet glass. KOG… has hundreds of color recipes, documented color combinations and numerous textures and densities,” the company web site says, with an illustration of handling molten glass better than I could photograph.

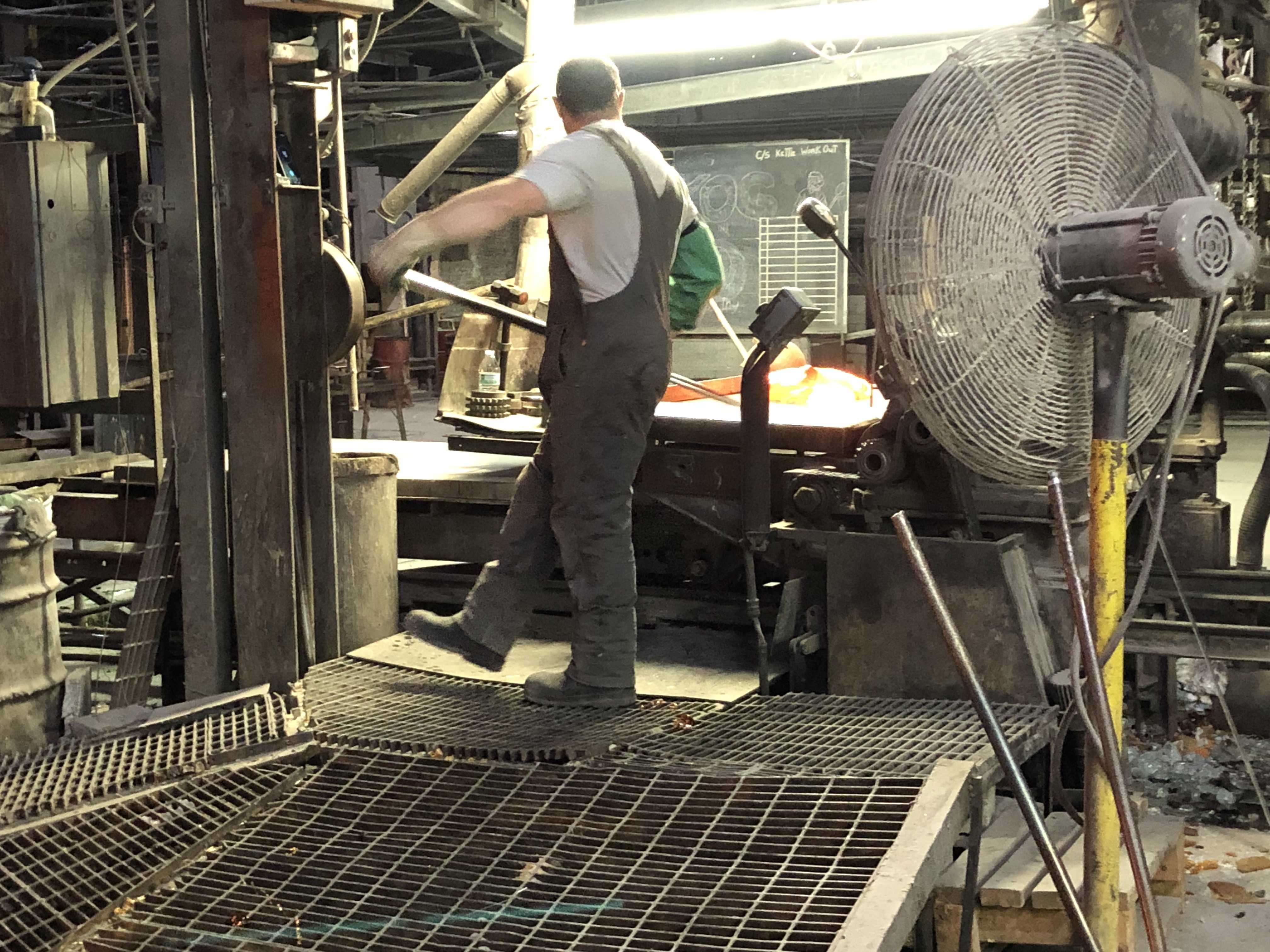

After the molten load has been dropped off at a suitable table-like surface to cool and be shaped, other glass experts do what they do.

Our knowledgeable guide told us about the chemistry and the process and the history of the place.

I didn’t understand a lot of it, especially the finer points of the process, but remained fascinated. As a glass artist herself, she also conveyed a sense of artistic wonder at the multitudes of glass, the colors and textures, which are both hard and fragile. All that came through a device to boost her voice, since a glass factory can be a noisy place.

Note the glass at her feet. Among other stipulations that we agreed to before taking the tour was no open-toed shoes. In fact, that was stressed the most. When moving globs of molten glass around, a little is naturally going to drop and harden on the floor. Then break. In the fullness of time, the factory workers remove the glass, perhaps to be remelted, or sold as random pieces by weight to artists who use it. But there’s always going to be some glass underfoot. Fortunately this wasn’t a problem with standard footwear.

Another thing the company tells you is that the factory has no climate control. So while it was just above freezing outside, the factory was warmed by the furnaces. In summer, of course, the effect would be additive, and so devilish hot on the factory floor. Away from the furnaces, in the spaces used for processing and storing and packing all that glass, temps were low in December.

Such as in the cullet barrel room.

Cullet. How did I get this far and not know there is a word for shards of glass, thought of collectively and probably destined to be remelted?

Most of the company’s product isn’t broken, and so is stored in an impressive array of racks and shelving.

Toward the end of the tour, we passed through a studio where artists employed by KOG work on custom projects. It being just before Christmas, only one was around, though I’m sure it’s a livelier place most of the time. And it is climate controlled.

Most of the complex is newer than 1888, but even so glass has been made on this site for nearly 140 years, using fuel unknown to the ancients. By ancient I mean really ancient: man-made glass from about 3500 BC has turned up in Egypt and eastern Mesopotamia, and it has been made ever since. So we visited a modern gas-power glass factory last month, but also experienced a vivid link to the heat and work of millennia.