As tourist attractions go, manhole covers might not be the stuff of dreams or adventure, but they do have their charms. For one thing, admission is always free. No timed tickets nor ID required, beyond the documents you used to travel to another country. You could also argue for their authenticity: manhole covers are by locals, for locals, even if they don’t pay much attention to them themselves.

Famous might not quite be the word, but Japan is known for its manhole covers. You can find plenty of articles about Japanese manhole covers on line, such as one about a detailed scouring for covers at an otherwise obscure spot in Sumida Ward, Tokyo. Fully illustrated with snaps, it’s a granular approach after my own heart.

Or the Atlas Obscura page, sketching out a history of elaborate Japanese manhole covers, which reportedly date from the 1980s, taking some decades to catch on. This page asserts that there is such a thing as the Japan Society of Manhole Covers, while providing a lot of good multi-hue examples. Alas, the link to the society is dead.

On the other hand, the site of the Japan Ground Manhole Association is up and running. It is more of an engineering group, but you can find out a bit about the history of manhole covers, if you let the machine translate for you.

“In the 1980s, a construction specialist from the Ministry of Construction’s Public Sewerage Division suggested that each city, town, and village create their own original manhole design in order to improve the image of the sewerage business and appeal to citizens, and this led to the advancement of design,” JGMA says, not naming the mid-level functionary.

“In 1986, the ‘Top 20 Sewer Manhole Cover Designs’ were selected, followed the following year by ‘Manhole Faces,’ in 1989 by ‘Road Emblems,’ and in 1993 by ‘Top 250 Ground Manhole Designs,’ all of which were published under the supervision of the Ministry of Construction’s Sewerage Division (Suido Sangyo Shimbunsha). As a result, business entities across the country began competing to develop designs.”

For a long look at the art of the Japanese manhole cover, this Flickr account stocks 5,700 manhole cover images from that nation.

Though manhole cover art was a thing by the early ’90s, I have to say I heard nothing about it then. By contrast, when we went to Japan in February, I knew I might see some interesting and even good-looking ones, but I also didn’t feel like seeking them out. That’s another good thing about manhole cover tourism: you don’t have to go to them. In some sense, as you walk around, they come to you.

One of the few in color. I saw more than one of these.

Or oriented this way. Not sure which is “correct,” or even better.

Even now, Expo 2025 is preparing to open on April 13, with a run until October 13. Every Expo worth its salt needs a mascot approved by committee, and there he – she – it is, on an Osaka manhole cover, with a design by picture book illustrator named Kouhei Yamashita. Called Myaku-Myaku, the – creature? – is part of a mascot subworld in Japan known as yuru-kyara, who are mascots for places. Other examples include Kumamon, a bear-like mascot of Kumamoto Prefecture; Funassyi, the anthropomorphic pear mascot of the city of Funabashi; and Chiitan, a “fairy baby otter” that’s a mascot for the city of Susaki.

Is Myaku-Myaku so easily characterized? Anthropomorphic, yes, but what else? What to make of the blobby ring peppered with eyeballs? A least it’s smiling. Otherwise it would look like it crawled out of a cheap horror movie.

No, he’s cute. Kawaii, as they say. One of the most important words in Japanese. People stopped to take pictures of another representation of the whatsit, on Nakanoshima Island in Osaka.

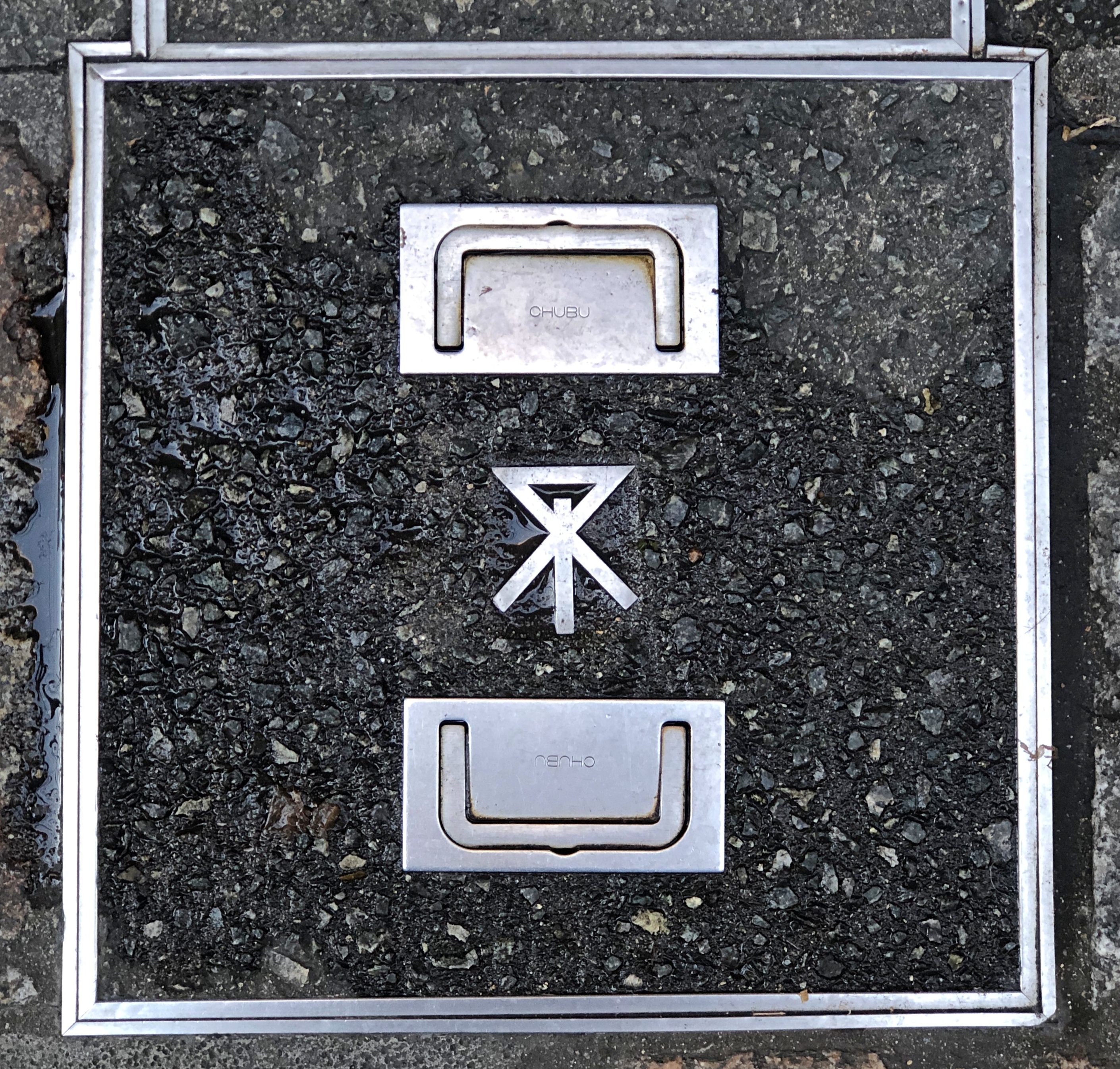

The Expo isn’t just a city event, so the seal of Osaka doesn’t appear with Myaku-Myaku. Other utility covers in the city do feature the good old miotsukushi, the device of the city.

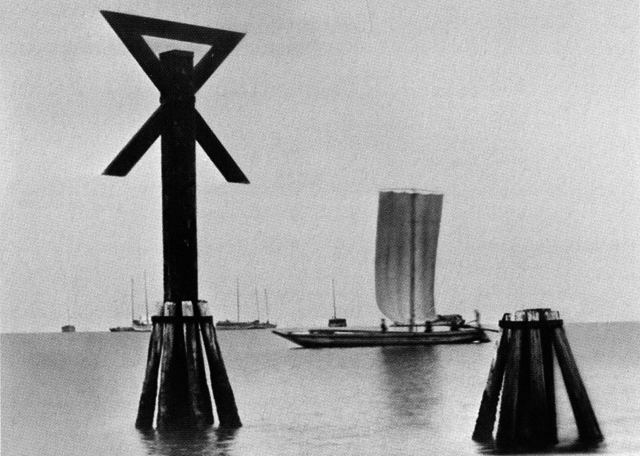

Miotsukushi were river markers on the rivers passing through Osaka. Navigation aids. Pictured in 1877.

As I wrote almost 10 years ago: Scenes of Naniwa tells us that “the Osaka city symbol, the miotsukushi originates from the stakes used as water route signals which up to the middle of the Meiji period stood planted in the Kizu and Aji Rivers, both debouching into Osaka Harbor. The depth of the water was difficult to judge because of the abundant bamboo reeds growing in the rivers… the miotsukushi planted along both sides of the rivers were signs showing that within those stakes the water was deep enough to sail through safely.”

A miotsukushi on a manhole cover to go with Osaka Castle and cherry blossoms.

In Nagoya. A busy one, depicting industry in the city, with the castle at the hub.

In Kamakura, more manhole covers.

The following one looks more like a metal plate mounted in the sidewalk than a utility cover, but in any case it is a tribute to local sports.

You can find it near the coast, just outside of Kamakura, and not far from where a bridge connects to Enoshima, a large island that’s home to a Shinto shrine, botanic garden and a number of scenic spots. The place is known for its surfing.

Winter wasn’t about to stop these surfer dudes.