As you enter the National Memorial for Peace and Justice on a hill in downtown Montgomery, Alabama — as we did on May 17 — it’s hard to see what’s ahead.

The path passes “Nkyinkyim Installation” by Ghanaian sculptor Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, erected with the memorial when it opened only last year. The work speaks for itself.

The path passes “Nkyinkyim Installation” by Ghanaian sculptor Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, erected with the memorial when it opened only last year. The work speaks for itself.

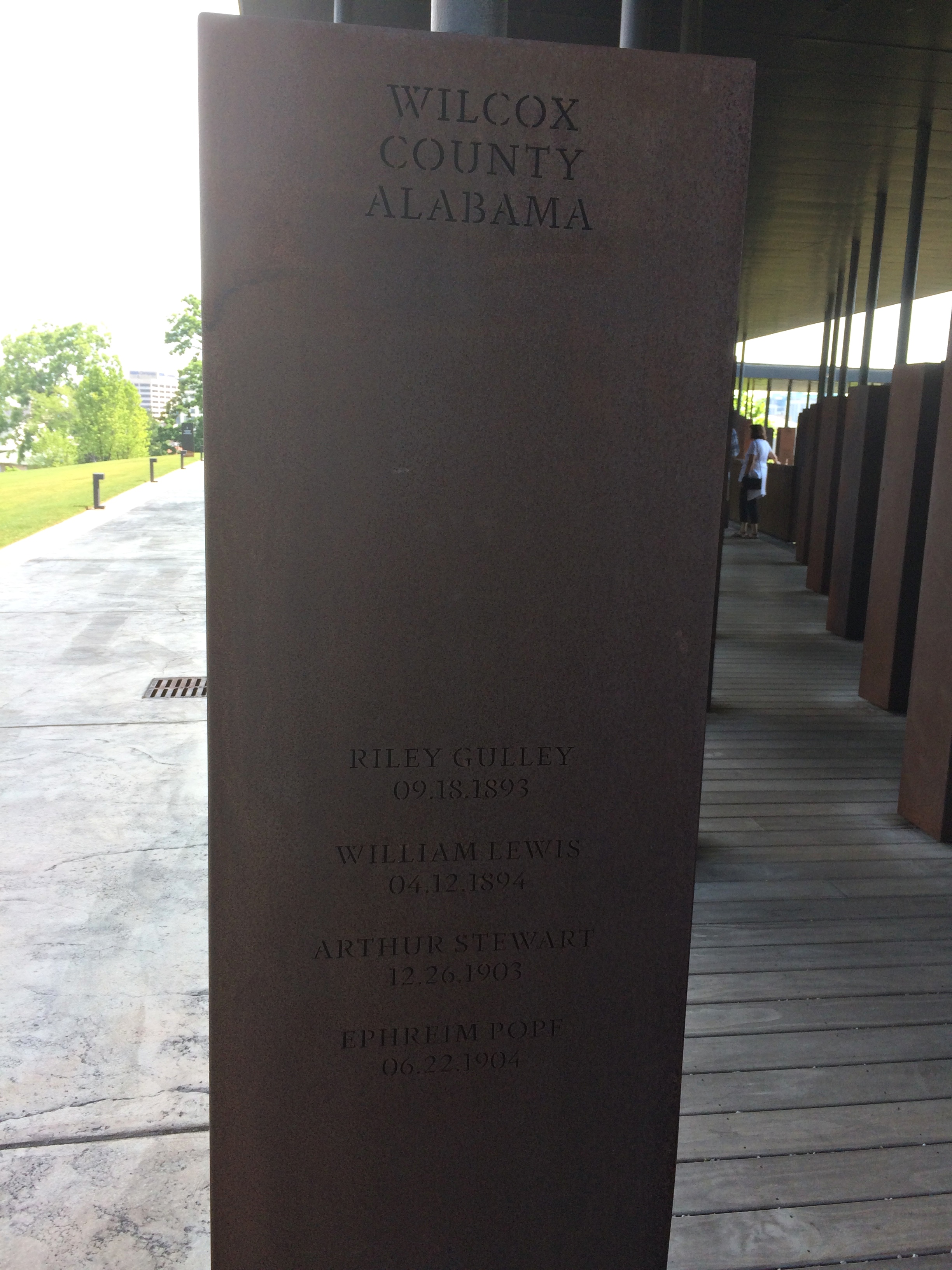

The memorial structure includes over 800 corten steel (weathering steel) monuments, one for each county in the United States where a lynching took place. Engraved on the columns are the names of the lynching victims documented for that county.

The memorial structure includes over 800 corten steel (weathering steel) monuments, one for each county in the United States where a lynching took place. Engraved on the columns are the names of the lynching victims documented for that county.

Here are the victims in Wilcox County, Alabama, to pick one of the first steel monuments you encounter: Riley Gulley, William Lewis, Arthur Stewart and Ephreim Pope.

Here are the victims in Wilcox County, Alabama, to pick one of the first steel monuments you encounter: Riley Gulley, William Lewis, Arthur Stewart and Ephreim Pope.

Visitors enter the memorial at one corner of the square shape. On the first side of the memorial, the steel monuments are flush with the floor, with the names at eye level or lower.

Visitors enter the memorial at one corner of the square shape. On the first side of the memorial, the steel monuments are flush with the floor, with the names at eye level or lower.

On the second side of the memorial, the floor begins to slope downward in the direction of travel, but the steel monuments continue to be at the same level.

In the third side of the memorial, the floor slopes even more and the effect becomes very noticeable. The steel monuments are hanging.

In the third side of the memorial, the floor slopes even more and the effect becomes very noticeable. The steel monuments are hanging.

You need to look up to see the county names.

You need to look up to see the county names.

The fourth side. The effect is practically tunnel-like by now.

The writing on one wall says:

The writing on one wall says:

For the hanged and beaten, for the shot, drowned, and burned, for the tortured, tormented, and terrorized. For those abandoned by the rule of law.

We will remember.

With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice. With courage because peace requires bravery. With persistence because justice is a constant struggle. With faith because we shall overcome.

Water flows down the other wall.

The text:

Thousands of African American are unknown victims of racial terror lynchings whose deaths cannot be documented, many whose names will never been known. They are all honored here.

Outside the memorial structure are smaller versions of the steel monuments arrayed in long lines, lying with their text face up. I understand that if a county named on one of them wants to use it as part of a local memorial to lynching victims, it will be given for that purpose. So far no county has taken any of them.

The Legacy Museum, developed by the same organization as the memorial — the Equal Justice Initiative — is also in downtown Montgomery, pointedly in a building where enslaved black people were imprisoned, near the site of the city’s 19th-century slave market. By the mid-1800s, Montgomery was the focus of the slave trade in Alabama.

In full, it is The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. It’s a small museum, 11,000 square feet, but a powerful one.

In full, it is The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. It’s a small museum, 11,000 square feet, but a powerful one.

The EJI web site for the museum says: “Visitors encounter a powerful sense of place when they enter the museum and confront slave pen replicas, where you can see, hear, and get close to what it was like to be imprisoned awaiting sale at the nearby auction block. First-person accounts from enslaved people narrate the sights and sounds of the domestic slave trade. Extensive research and videography helps visitors understand the racial terrorism of lynching, and the humiliation of the Jim Crow South.”

The museum also illustrates that the more recent (and ongoing) war on drugs, a toxic interplay of political calculation and moral panic, has made black Americans “vulnerable to a new era of racial bias and abuse of power wielded by our contemporary criminal justice system.”

A quote from the all together remarkable EJI Director Bryan Stevenson, who lead the effort to build the memorial and create the museum:

“Our nation’s history of racial injustice casts a shadow across the American landscape. This shadow cannot be lifted until we shine the light of truth on the destructive violence that shaped our nation, traumatized people of color, and compromised our commitment to the rule of law and to equal justice.”