One upon a time, gaming businessman William Harrah owned a lot of cars, maybe more than any single individual ever. The dosh to put his collection together came from Harrah building a large hotel and casino empire in Reno and other places in the years after WWII. Sources put the number of vehicles at around 1,400, but maybe that’s an undercount.

Harrah died in 1978. Eventually, most of his cars were sold at auction, but a nucleus of the collection remained intact and formed the basis of the National Automobile Museum in Reno. Intrigued by the prospect of seeing them myself, especially with the impressive Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum in Fairbanks in mind, I arrived not long before noon on October 3.

Auto museums are a fairly new interest of mine, spurred by my good experience in Alaska last year. And why not? I like good airplane collections and historic trains, too. If I’m ever in southern Germany again, I’d look at the Zeppelin Museum as well, because how cool is that?

The scope of the Reno museum is wider than the one in Fairbanks, considering that it has cars from the dawn of automotive travel through close to the present day, as opposed to a collection that extends only until the end of the 1930s. Quite a lot to see, beginning with the beginning.

That’s an 1892 Philion. I’d never heard of it either, and for good reason: this is the only one. There only ever was one, since it was never intended to be mass produced. The story of its owner is just as interesting as any of the mechanical aspects of the vehicle.

Achille Philion, a French acrobat and showman in the U.S. who called himself the Great Equilibrist and Originator, acquired a steam-powered quadricycle and had it modified, even going so far as to register a few patents associated with early autos. He used the car to draw attention to his performances, which involved — well, let a poster tell the story. Nothing really to do with automobiles.

According to the plaque at the museum, the car changed hands a number of times after Philion sold it, and it even made an appearance in The Magnificent Ambersons.

Other early autos at the museum include the 1899 Locomobile, one of the first production autos in the U.S., and another steamer. Cool name.

Auto design and innovation progressed quickly in the ’00s. Pretty soon carmaker Thomas Motor Co. created a car that could drive most of the way around the world: The 1907 Thomas Flyer.

As far as I’m concerned, this was the centerpiece of the museum. Sure, there are also dozens of cars from early motoring, sleek pre-WWII machines, mid-century racecars, and the Batmobile driven by Adam West, among many, many interesting vehicles.

This isn’t an example of just any 1907 Thomas. This is the car that won the 1908 New York to Paris Automobile Race, traveling 22,000 miles by land and sea over 169 days, despite there being very little in the way of infrastructure to support such a drive.

“After this victory, Thomas auto sales increased for a period; however, by 1912, the company was in receivership,” the sign at the museum says, and the car was sold during the bankruptcy proceedings.

William Harrah found it in the early 1960s, neglected and forgotten, and authenticated its participation in the race in a most amazing way, namely by bringing George Schuster, who had driven the car to victory in 1908, to Reno. Schuster was 91 at the time (he lived to be 99), and “during the dismantling of the Flyer, [he] witnessed cracks in the frame and repairs he had made during the race, proving its authenticity. The Thomas Flyer was restored to the condition [it was] when it finished the race.”

Elsewhere in the museum is this.

It shows the route of the race.

Accounts of the race say the prize for winning wasn’t money, but honor and glory — and “a trophy.” The plaque at the base says this globe was indeed presented to the Thomas Motor Co. by the organizers, so I guess this is it.

One more legacy of the race: it inspired The Great Race. Among silly early ’60s epic-long movies, it’s one of the more silly (and could have been trimmed by an hour with no loss).

Moving on to other fine machines of the pre-WWI period. A 1908 Brush (gas), a 1909 White (steam), and a 1912 Selden (gas), respectively.

Those were just part of the contents of one room. Other rooms had more recent vehicles. Such as these arrays.

“[It] has a 6-cylinder OHC fuel-injected engine developing 240 hp with an advertised top speed of 146 mph… The car was entered in the 1959 Bonneville Salt Flats Class D speed trials and set a new record at 143.769 mph,” the museum says. Those doors are referred to as “gullwing.”

The Hudson line lasted only until 1957. By that time, the company was known as American Motors Corp., which had a future ahead of it that included the AMC Pacer. I didn’t have one, but a friend of mine in high school did, and I remember it fondly. Maybe more than he does.

Uncomfortably close to its origins as the people’s car of National Socialism, but never mind. Another high school friend of mine had a ’73 Super Beetle, and occasionally he took that car to places where cars really weren’t supposed to go. What a gas.

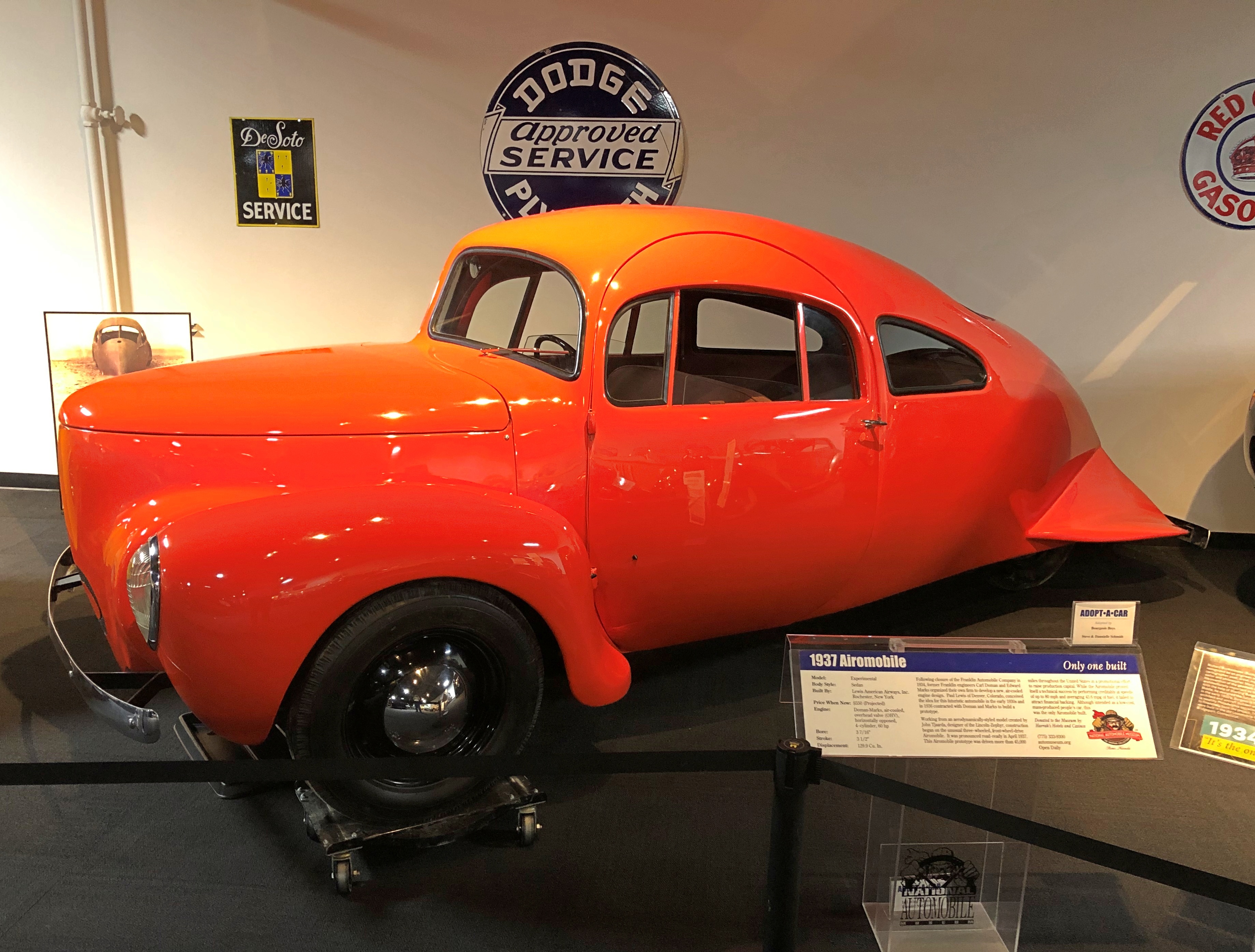

The museum’s collection also includes a fair number of less-than-standard cars. Take the three-wheeled, piscine 1937 Airomobile, for example.

The only one ever built. “It failed to attract financial backing,” the museum explains drily.

Maybe the ultimate vehicular oddity is the 1934 Dymaxion.

Looks something like a Volkswagen Microbus except, of course, for having three wheels and an even rounder contour. Bucky was trying to smash paradigms, but no go: only three prototypes were built — and this is the only one still in existence. Still, revisionist thinkers closer to our time admire the Dymaxion. Well, maybe. Fuller’s house design didn’t catch on either, but it is interesting to look at.

The museum also has an impressive cache of cars used in movies and TV shows, such as in The Green Hornet, a modified 1966 Imperial, one of two created for the show by car remodeler Dean Jeffries.

A close replica of the DeLorean put to such good use in Back to the Future. More gullwings.

And of course — what could be better? — a Batmobile (a modified 1966 Lincoln).

An original George Barris Batmobile, the museum says, and you can see Barris’ autograph inside, along with those of Adam West and Burt Ward.

All together, the museum sports a fun lot of cars to see, even if you’re not too keen on all the technical specs. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that its collection includes plenty of other other car-related items. My own favorite were a line of vintage gas pumps. Rare to see anything like them in situ, but not impossible. Modern gas pumps pale (stylistically) by comparison.

After all, without gas, where are all those cars going to go? Unless they’re steamers. Imagine the advanced steamer tech we’d have now — we wouldn’t think a thing of it — if they’d caught on instead of internal combustion, or even developed in parallel.