Marion, Ohio, a burg about 36,000 residents 50 miles north of Columbus, happens to be along the route we took south from Michigan on the second day of our trip, March 18. It also happens to be the hometown of Warren G. Harding, which pretty much guaranteed a stop there by us.

After his sudden and unexpected death in office almost 100 years ago, the nation’s grief for its popular president allowed for the construction of an impressive memorial, finished in 1927 and, as Wiki points out correctly, the last of the big presidential memorials (at least so far). Donations paid for it, including pennies from schoolchildren, back when a penny could actually buy something small rather than nothing at all.

We arrived at the memorial in the afternoon. It was cold and very windy. The structure is whiter than I’d think it would be considering its 90-plus years in the elements, but I suppose the good people of Marion keep it maintained. Warren G.’s the only president they’re ever like to produce, after all.

Its marble Doric columns rise to support an entablature, but not a roof. Harding reportedly wanted to be buried under an open sky, and this was architect Henry Hornbostel and his partners’ way to honor that request.

Warren and Florence Harding are indeed buried within, and under the open sky.

A few miles away is the Harding house, built in the 1890s at the time of the Hardings’ marriage, when he was a newspaper editor and publisher and she a wealthy divorcee. The Marion Star, his paper, is still around, though it’s a Gannett asset these days.

We arrived too late to tour the house, but you can wander around the grounds. Yuriko and the dog had enough sense to stay in the car while I did this, in a wind that felt like it was going to freeze my face off.

Still, I got the satisfaction of standing on the very porch where Harding ran his front porch campaign for president beginning in the summer of 1920, briefly reviving the late 19th-century practice. He would be the last president to do so (as yet, unless you count the zoom campaigning of Joe Biden exactly a century later).

Marion will probably never have a summer, or any other season, like it again. The world came to Marion in 1920, including delegations from groups nationwide to offer their greetings to candidate Harding, and presumably many other people who showed up to hear the speeches he gave on the porch or otherwise join the festivities.

Speaking from the porch didn’t mean a lack of attention elsewhere in the country. The Harding campaign had a small house built on the grounds, which still stands, for the use of the press covering him.

Behind the main house is the Warren G. Harding Presidential Library & Museum which, as any presidential museum does, tries to put a good face on its president and administration. I will give the place credit for mentioning the various scandals the period is known for, such as Teapot Dome.

It’s also forward in acknowledging that his mistress Nan Britton had a daughter with Harding, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, who died only in 2005. As well it should, since DNA evidence in the 21st century has fingered then-Sen. Harding as the baby daddy.

As for his other known mistress, the married Carrie Fulton Phillips, the museum notes, “when she appeared at Harding’s front porch campaign, Republican party members paid for the Phillipses to take a lengthy trip abroad.”

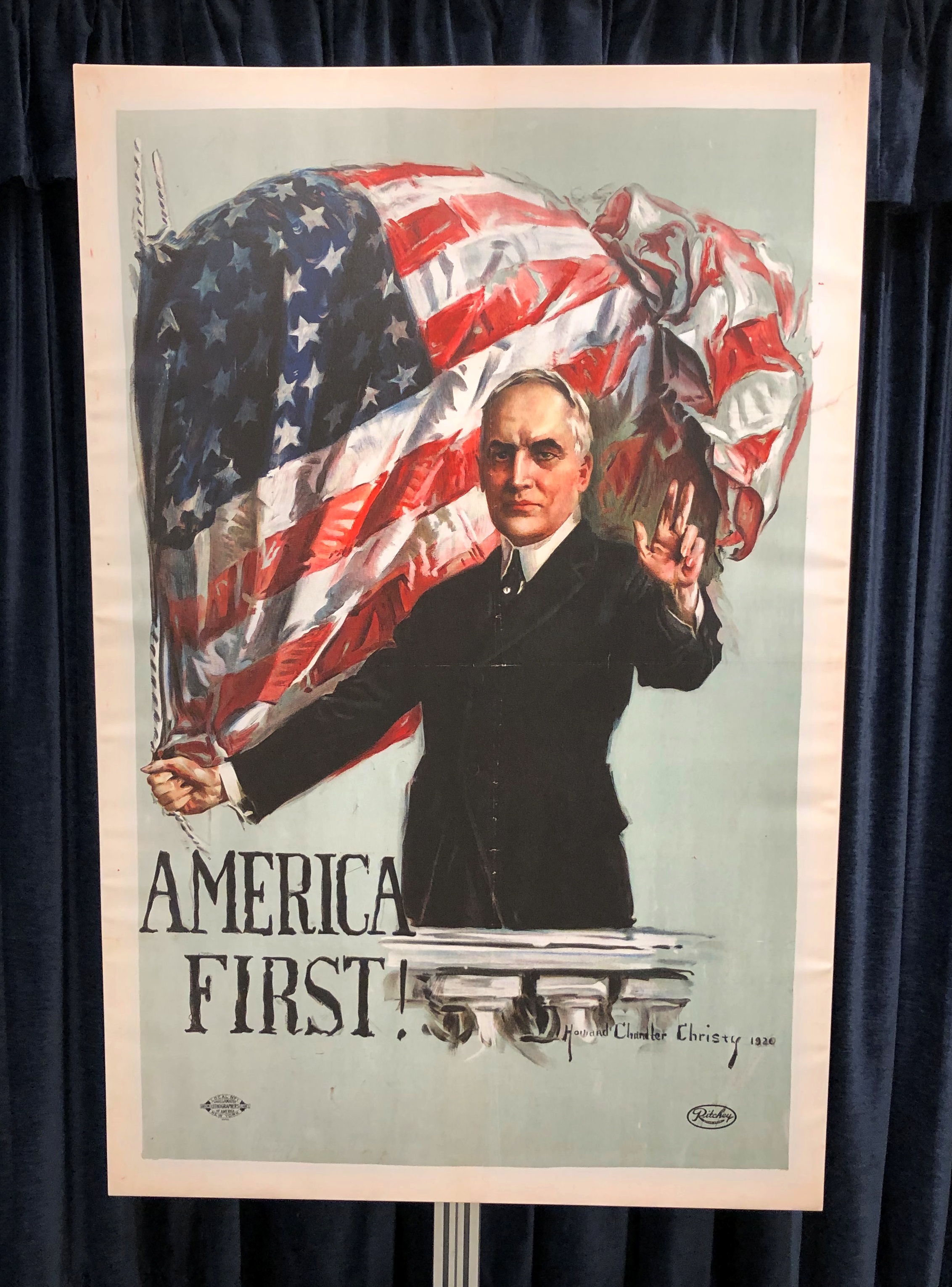

Still, a triumphant Harding is in evidence. At least while in campaign mode. Not bad for a compromise candidate picked by the 1920 Republican National Convention.

Events could have gone another way. Leonard Wood could have been the nominee in 1920 and gone on to the presidency. Or Frank Lowden might have been tapped. Or, had TR lived a little longer (d. 1919), he might have captured the prize and returned to office (at my age, TR had been dead more than a year).

Harding might merely be an obscure senator buried in a more modest plot in Marion, rather than an increasingly obscure president in a grand tomb the likes of which is completely out of style. But that isn’t how it happened.

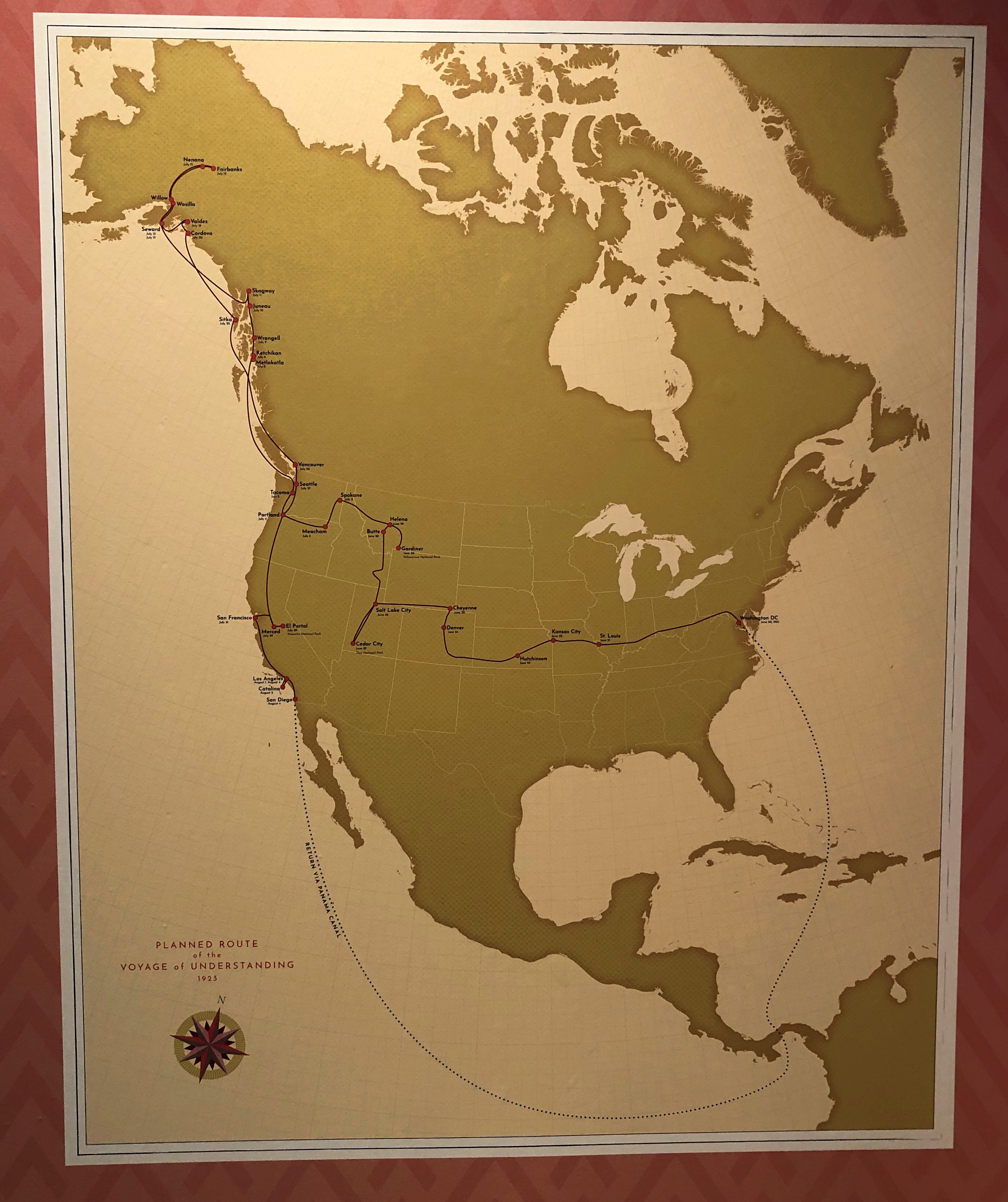

Historians roundly deride Harding, and I believe there’s some basis for it, but my own estimation of the man himself inched up a notch or two when I read, per the museum, that Harding and his wife were avid travelers well before they occupied the White House. That was part of the impetus for the famed long trip that he took as president in 1923, and which was interrupted by his death.

I didn’t know that Harding called it “The Voyage of Understanding.” Quite a route.

Some of the museum’s artifacts are odder than others, including this one from the Voyage.

That’s a papier-mache potato, about a yard long, that the citizens of Idaho Falls, Idaho gave to President Harding when he passed through in 1923.