Why Kansas? Even the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center web site asks that question in its FAQ page. Why is a first-rate spacecraft museum – absolutely the best I’ve ever seen, except for the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum – in Hutchinson, Kansas, a town of about 42,000 northwest of Wichita? The answer: that’s the way the cookie crumbled. Right place, right time.

“The Cosmosphere began in 1962 as nothing more than a tiny planetarium on the Kansas State Fairgrounds,” the page says. When the planetarium outgrew its original facility and moved to its current location, Patricia Brooks Carey and the Hutchinson Planetarium’s board of directors sought business advice from Max Ary, then director of Ft. Worth’s Noble Planetarium. “Interestingly, Ary was also part of a Smithsonian Institution committee in charge of relocating thousands of space hardware artifacts to museums throughout the U.S. The Cosmosphere was granted many of the artifacts.”

These days the museum measures over 105,000 square feet and includes a large exhibit space for rockets and spacecraft, plus a planetarium, dome theater, and more. We arrived in the mid-afternoon of July 13, too late to catch a planetarium show, but in plenty of time to look at a lot of space stuff, expertly and chronically organized for display.

“Most everything you see in the museum was either flown in space, built as a back up for what was flown in space, built as a testing unit for what was flown in space, or was the real deal, but was never meant for space,” the museum continues. “Only a few artifacts are replicas, and those that are replicas, are for good reason. For example, the lunar module and lunar rover in the Apollo Gallery are replicas (though built by the same company that produced the flown modules), because those that went in space, stayed in space. No museum in the world carries a flown lunar module or rover. In fact, they’re all still on the Moon.”

The displays begin at the beginning of modern rocketry – Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Robert Goddard and on to Nazi rockets, including a restored V-1 and V-2.

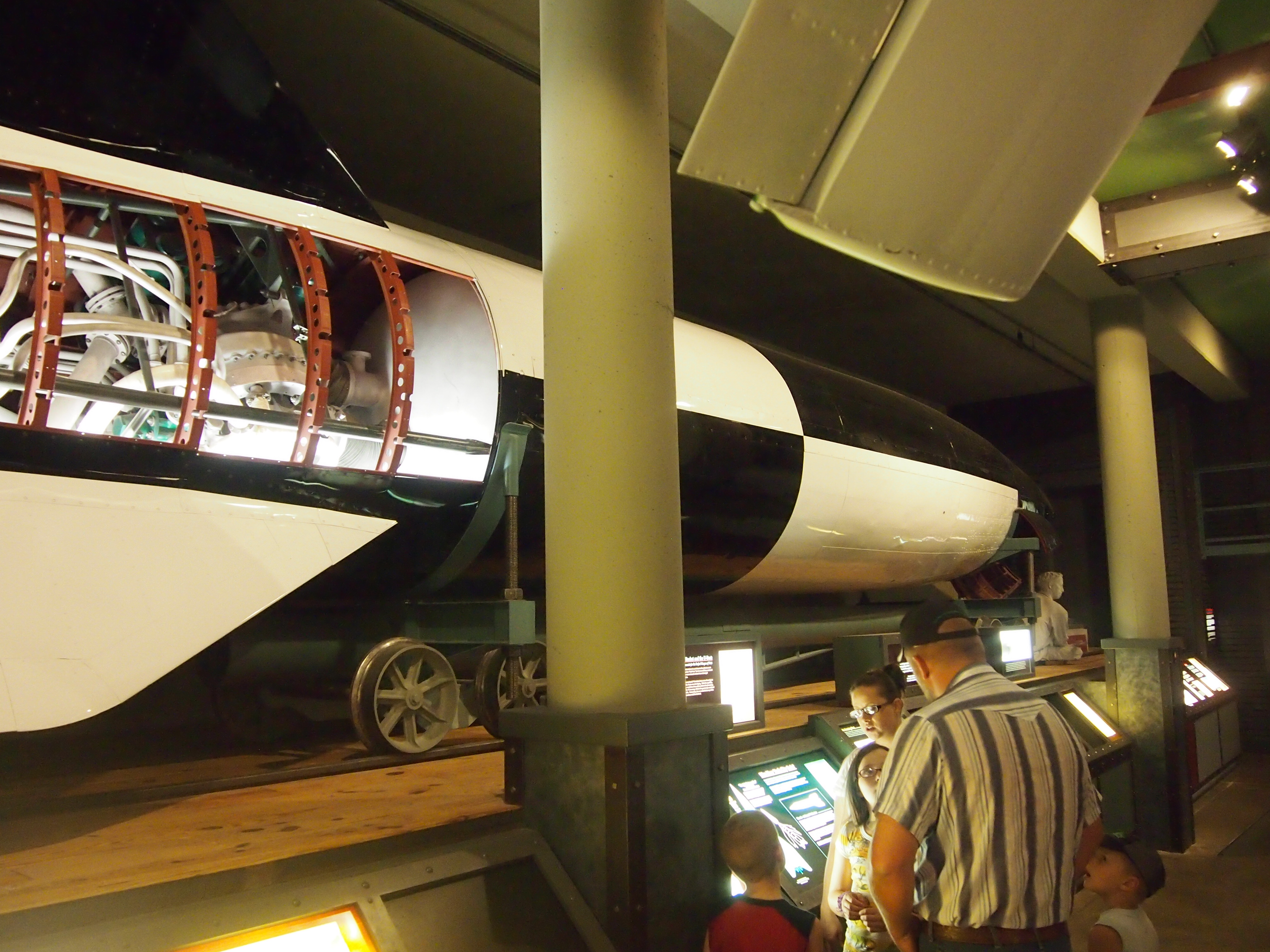

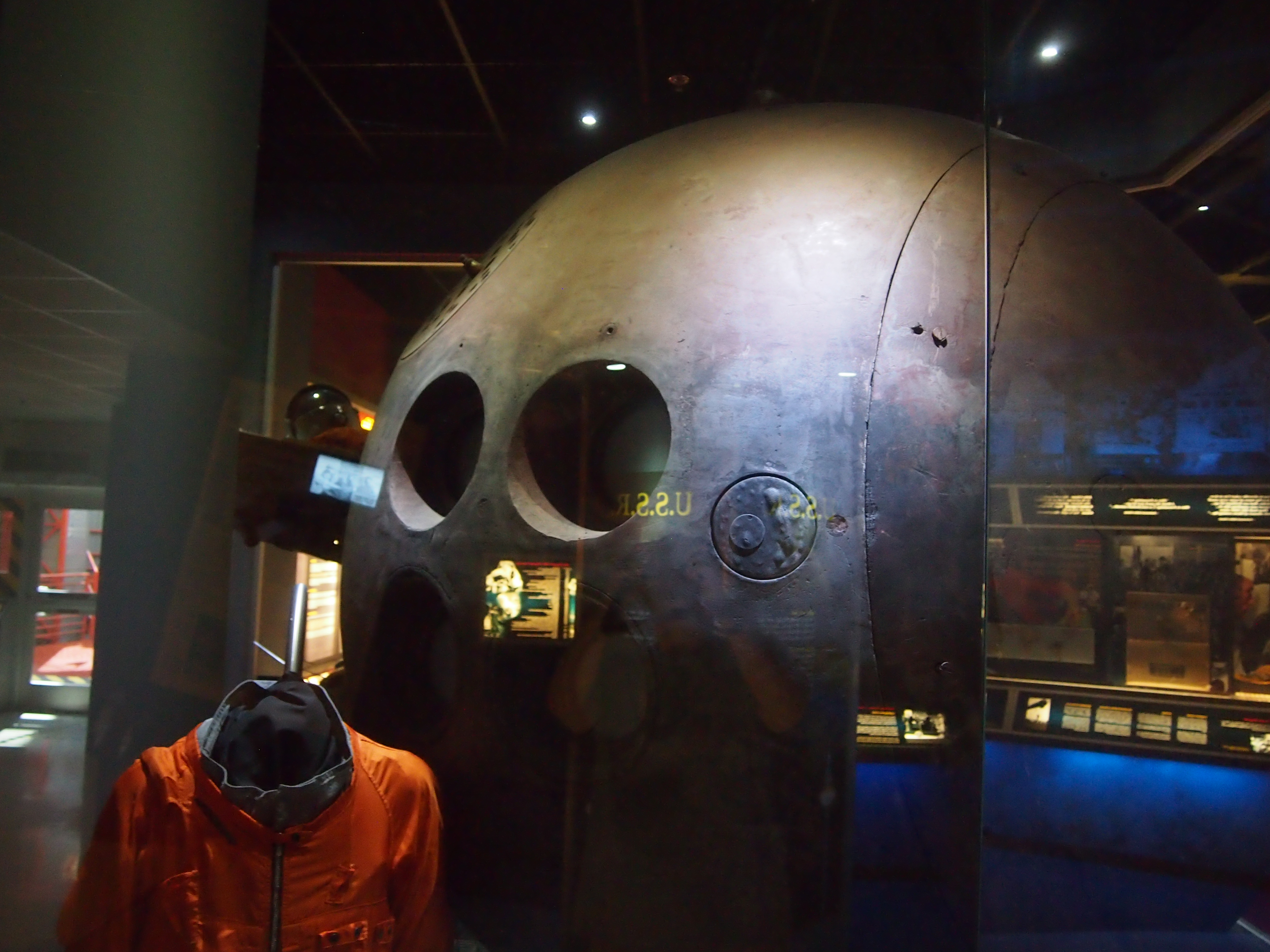

Then on to Soviet and U.S. rockets and capsules that ventured into space, plus a lot of ancillary items. It’s an astonishing collection, including a replica of the X-1, a flight-ready backup for Sputnik 1, a backup version of the Vanguard 1, a Russian Vostok capsule – the only one outside Russia – Liberty Bell 7 (pulled from the ocean floor and restored), a Redstone rocket and a Titan, too, the Gemini 10 capsule, a Voskhod capsule, the Apollo 13 Command Module, a Soyuz capsule, various Soviet and American rocket engines, an Apollo 11 Moon rock, and a lot of smaller artifacts.

Then on to Soviet and U.S. rockets and capsules that ventured into space, plus a lot of ancillary items. It’s an astonishing collection, including a replica of the X-1, a flight-ready backup for Sputnik 1, a backup version of the Vanguard 1, a Russian Vostok capsule – the only one outside Russia – Liberty Bell 7 (pulled from the ocean floor and restored), a Redstone rocket and a Titan, too, the Gemini 10 capsule, a Voskhod capsule, the Apollo 13 Command Module, a Soyuz capsule, various Soviet and American rocket engines, an Apollo 11 Moon rock, and a lot of smaller artifacts.

I took a particular interest in the Russian equipment because I’ve seen so little of it. In fact, I’d never seen a Vostok, and there it was. Looking like a large bowling ball behind glass. “Hop in, Comrade, and we’ll shoot you into space.”

The American equipment was impressive, too, though more familiar. It’s always an impressive thing to stand under a rocket like a Titan, which used to deliver Gemini into orbit.

The American equipment was impressive, too, though more familiar. It’s always an impressive thing to stand under a rocket like a Titan, which used to deliver Gemini into orbit.

Ann seemed to enjoy herself, and probably learned something. But to really appreciate this museum, it helps to have been an eight-year-old boy in 1969. You find yourself turning the corner and saying, “Wow, look at that!” a lot.