Funniest thing I’ve heard in a while, at least in the category of unintentional comedy. The narrator of a video about The Wire that I watched today – just finished the third season, watching once a week or so – broke narrative for a commercial.

“If Omar is coming for you, you’ll need the perfect shoe to get away,” he said, holding up a pair of some running shoes.

Drive about six hours from metro Chicago, south past St. Louis on the state of Missouri side of the Mississippi River, go almost as far as Farmington, Mo. (pop. 18,200) and leave the main road, but only a short distance down a side road, and you’ll find a place to ruminate on time and decay and poisoning. If you’re the ruminating sort.

Another day, another day exposed to the elements for the former industrial structures at Federal Mill No. 3, which processed zinc and lead ore from 1906 to 1972 and became property of the state shortly after its closure. It’s now Missouri Mines State Historic Site. Smelting does what it does, leaves slag and moves on. The weathered, rusty structures should count as a kind of slag, but one you can look up at in some awe.

We’d arrived about an hour before the grounds closed on the afternoon of April 5. Except for one state park service employee, no one else was around, though there were signs advertising an upcoming eclipse event, since this part of Missouri was in the path of totality. Bet the place was overrun for that.

Before coming to the Lead Belt of Missouri, I’d vaguely thought that lead mining was only an historic phenomenon, something like the copper mining in the UP that left behind relics. Missouri Mines didn’t do anything to correct that impression, at least at first. Later I found out was wrong.

“Lead and fur were the most important exports from Missouri during its early years as a Spanish, French, and then United States territory (Burford, 1978),” wrote Cheryl M. Seeger in a monograph called, “History of Mining in the Southeast Missouri Lead District and Description of Mine Processes, Regulatory Controls, Environmental Effects, and Mine Facilities in the Viburnum Trend Subdistrict” (2008).

“Southeastern Missouri, with the largest known concentration of galena (lead sulfide) in the world, was the site of the first prolonged mining in the state and has produced lead almost continuously since 1721,” Seeger notes. Largest in the world? Who knew? (Besides Cheryl Seeger, that is.)

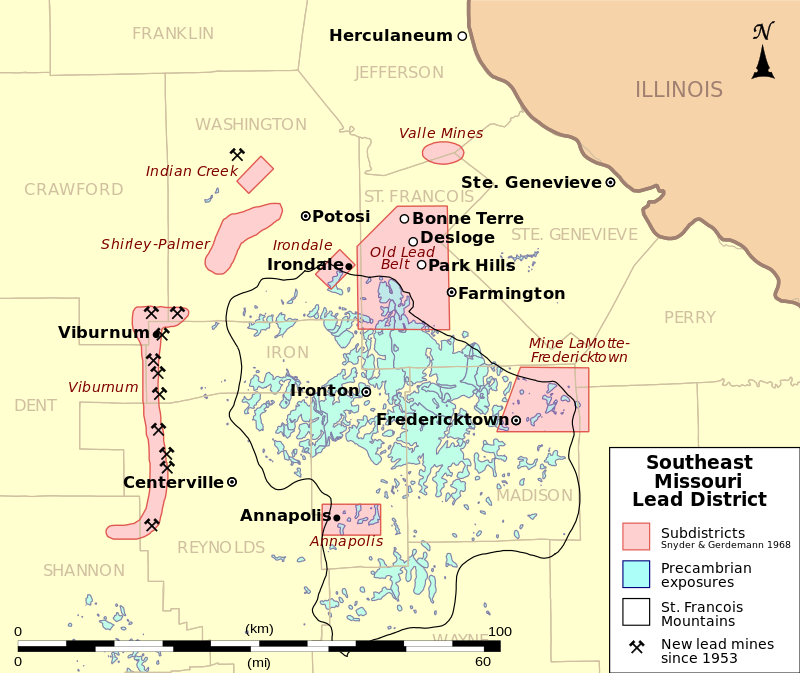

Wiki published a map to illustrate the point, posted by one Kbh3rd, who is duly acknowledged here under the terms of Creative Commons 3.0.

Looks like all the mining action migrated to the west, but not far west, in the 20th century. In the monograph, I also learned that Moses Austin was a lead miner in the region – more about him later.

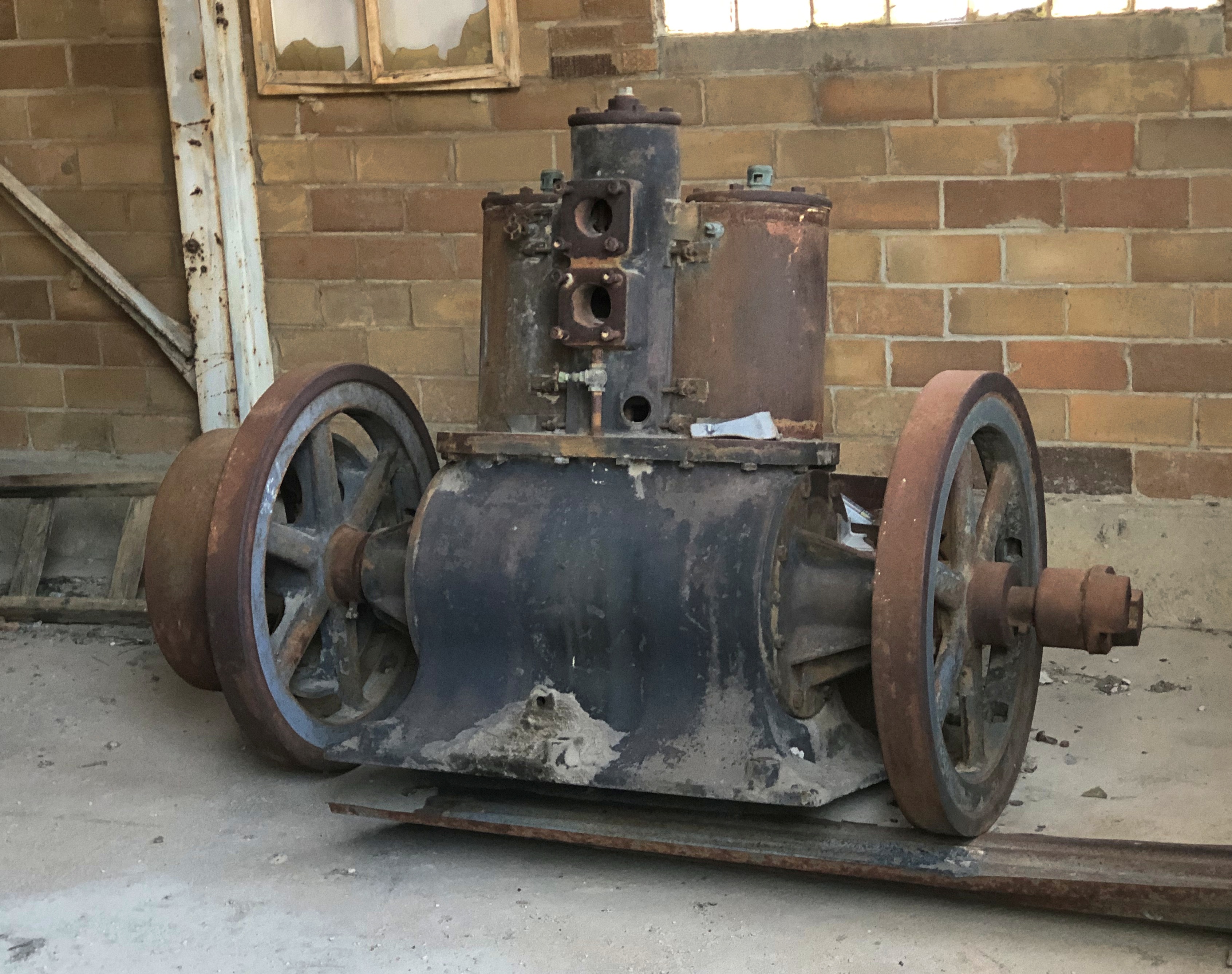

Most of the buildings at Missouri Mines SHS were roped off, and probably for good reason. But large windows were open, allowing a look inside the largest of them.

Mighty ruins are one thing, but I also like the smaller pieces.

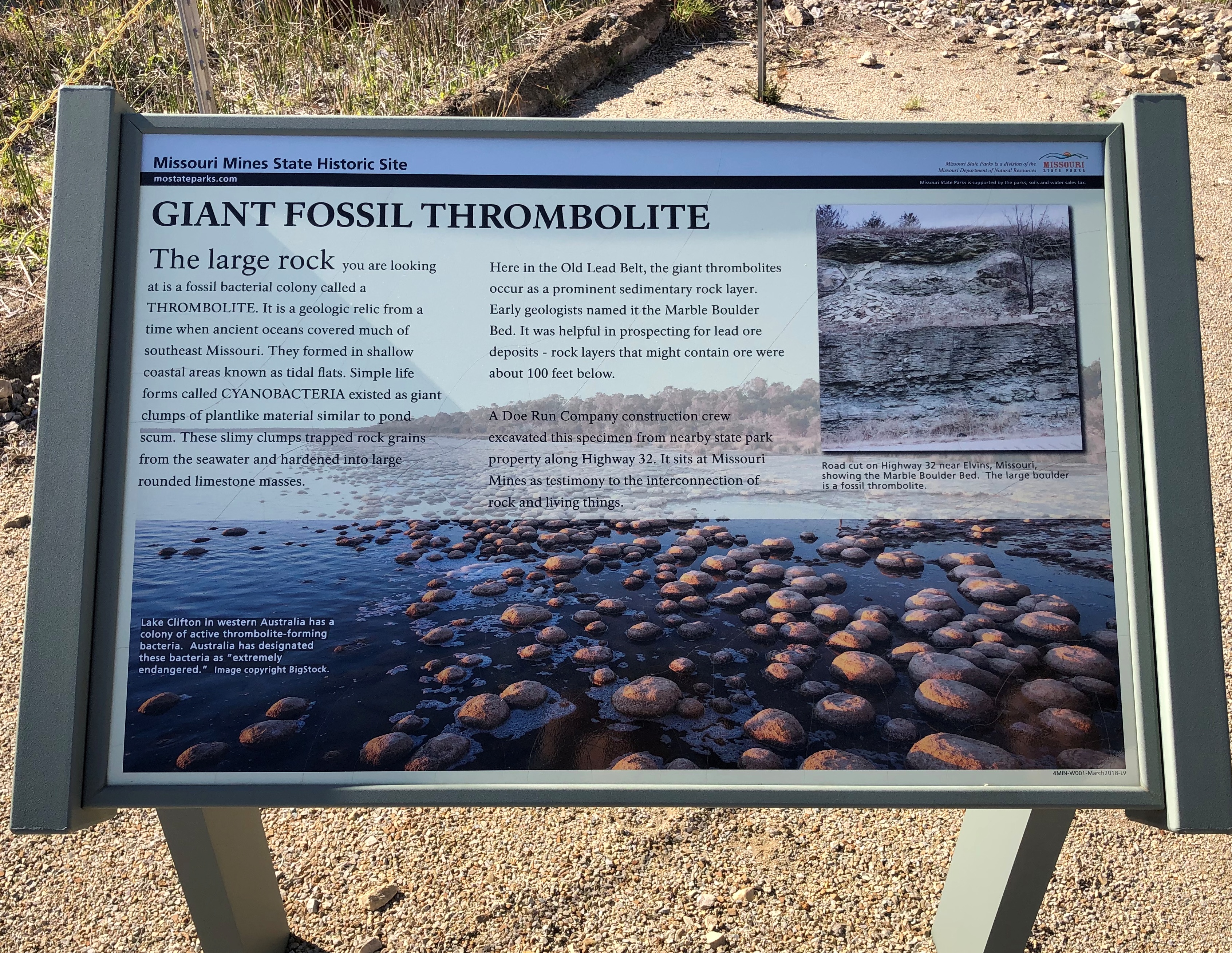

An oddity, but one dug up nearby.

A giant fossil thrombolite, a nearby sign said. Fossilized creatures, if you can call them that, from a billion years ago.

Next to the state historic site is St. Joe State Park, with a path leading into that park. The day was warm, but not too warm for a walk. It was then we realized the thing we’d forgotten for the trip, because there’s always something: hats. But we managed.

It was like walking straight into one of the more desolate parts of the West instead of lush, springtime Missouri.

Another legacy of lead mining: ruined land, considered fit only for off-road vehicle tracks these days. Look at enough maps of the Lead Belt, and you’ll find the Superfund maps, too – which cover most of the area.

Is there Superfund site tourism? There must be. No? Now there’s an opportunity for some gritty tours, believe me.

Or maybe infrastructure tourism.

Sign me up for that one.