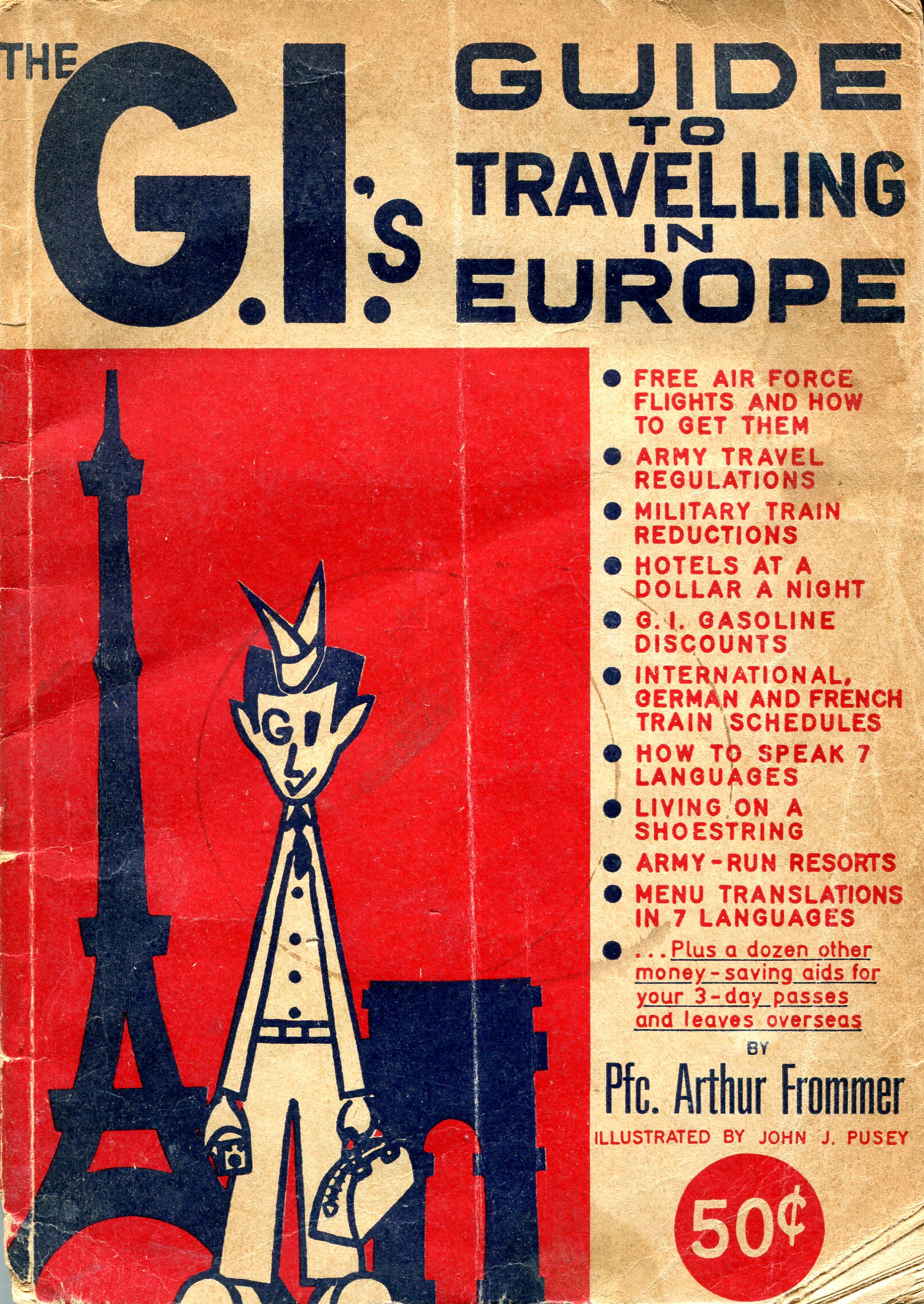

Among the many books at my mother’s house, I found a copy of The G.I.’s Guide to Travelling in Europe, by Pfc. Arthur Frommer, first printing, dated August 1955. The book isn’t crumbling yet, but at 60 years of age it’s distinctly yellow, and at risk of falling apart if I handle it too much. Probably the only reason it hasn’t fallen apart already is that no one has handled it much since my parents came home from Europe in 1956.

At the risk of damage, I took a look inside the book. It’s precisely what I’ve read it is — the first modern travel guide for a mass audience. In this case, U.S. military personnel stationed in Europe in the mid-50s. In the case of its successor title by Frommer, Europe on $5 a Day, American civilians traveling to Europe during that decade who had neither the time nor funds for a Grand Tour-style trip. Which would be most people.

At the risk of damage, I took a look inside the book. It’s precisely what I’ve read it is — the first modern travel guide for a mass audience. In this case, U.S. military personnel stationed in Europe in the mid-50s. In the case of its successor title by Frommer, Europe on $5 a Day, American civilians traveling to Europe during that decade who had neither the time nor funds for a Grand Tour-style trip. Which would be most people.

The focus is on how, rather than what. Chapters include: Army Travel Regulations, Free Air Force Flights, Train Travel in Europe, the G.I. and His Auto, Cities, Hotels & Restaurants, Army-Run Resorts, Talking Through Europe, Menu Translations, Changing Your Money.

The book’s done in a conversational, nuts-and-bolts sort of style, and quite well written. Besides the fact that Frommer was filling an unfilled niche, I can see why his books succeeded: useful content, done well.

The book’s done in a conversational, nuts-and-bolts sort of style, and quite well written. Besides the fact that Frommer was filling an unfilled niche, I can see why his books succeeded: useful content, done well.

“But where do I, as the author of this thing, get off posing as an expert on the subject?” Frommer wrote in the book’s introduction. “I’m a G.I. about to rotate home after more than a year of Army service in Germany. This was my first trip to Europe, and I wanted to see lots of it. During that year, therefore, I’ve taken the full allotted leave period of 30 days. I’ve requested and received, in addition, a 3-day pass per month. I’ve also traveled on several 3-day weekends resulting from Army holidays.

“In this manner, during a year of busy Army duty, I’ve been able to spend a full 3 to 10 days at every one of the following places: Paris, Rome, Madrid, Berlin, London, Barcelona, the Island of Mallorca, Vienna, Florence, Venice, Zurich, Munich, Frankfort, Innsbruck, Copenhagen, and Amsterdam.

“The entire amount of this travelling has been done solely on the proceeds of an Army salary that has never been higher than a Pfc’s pay. No money from home has ever defrayed any of these costs. Nor have I gone without coffee, razor blades and fresh laundry during the on-post portions of my Army life.

“Nor have I endured any grinding discomfort on any of the trips described… as the miles piled up, I learned; and the ordinary accumulation of experience was supplemented by a constant search for the gimmicks and short-cuts of European travel. I wrote for regulations and interrogated everyone I met. I was a pest, but I was able to accomplish a type and amount of travelling on the continent which — without fear of exaggeration or boasting — would’ve cost the ordinary civilian tourist over a thousand dollars, as well as months of free time. All at the expense of our benevolent Uncle.”

I hope my parents got their 50 cents’ worth out of the book. I’ll wager they did. I know they went to London, Paris, Strasbourg, Rome, Venice, and some other places from a posting in Germany. I rarely used any of Frommer’s later books myself in Europe or Asia, but I consulted others in the same style, and so have benefited from his work as well.

I’m also reminded of something my friend Dan, stationed in Germany as a Army lieutenant in the mid-80s, told me. By then, of course, getting around cheaply was easier (and there was no euro to mug you in places that should be cheap, like Italy and Greece). A handful of his men, Dan said, made an effort to go as many places as free time would allow, a la Frommer. A good many others, however, were content to hang around nearby and drink Bud.

Frommer, by the way, is still alive at 86. A few years ago, my friend Ed met the man in New York and did some walking around with him there. He says that was quite an experience, and I believe it.