The only place we visited during Open House Chicago on Sunday that wasn’t in the northwest part of the city or in near suburban Oak Park was Our Lady of Sorrows Basilica on the West Side. Or more formally, the Basilica of Our Lady of Sorrows.

In our time, the neighborhood is blighted. Across the street from the basilica are more modest structures.

In our time, the neighborhood is blighted. Across the street from the basilica are more modest structures.

But as mendicants, I expect the Servite Order that runs the basilica wouldn’t want to be in a posh neighborhood. The basilica itself, however, is jewel-box ornate.

But as mendicants, I expect the Servite Order that runs the basilica wouldn’t want to be in a posh neighborhood. The basilica itself, however, is jewel-box ornate.

Design credit is given to three gentlemen: Henry Englebert, John F. Pope, and William J. Brinkmann, with the structure going up from 1890 to 1902. I encountered a Brinkmann work earlier this year, out at Mount Carmel Cemetery.

Design credit is given to three gentlemen: Henry Englebert, John F. Pope, and William J. Brinkmann, with the structure going up from 1890 to 1902. I encountered a Brinkmann work earlier this year, out at Mount Carmel Cemetery.

No citation for it, but I have to mention his demise, as described by Wiki: “Brinkmann’s death was unexpected, gruesome and mysterious: his mangled, decapitated body was found on train tracks near 73rd street in February 1911… yet contradictory evidence prevented an inquest from finding a clear reason for his death or a finding of murder.

His funeral was held at St. Leo’s Church on 78th Street, a church he had himself designed in 1905. His death remains unsolved to this day.”

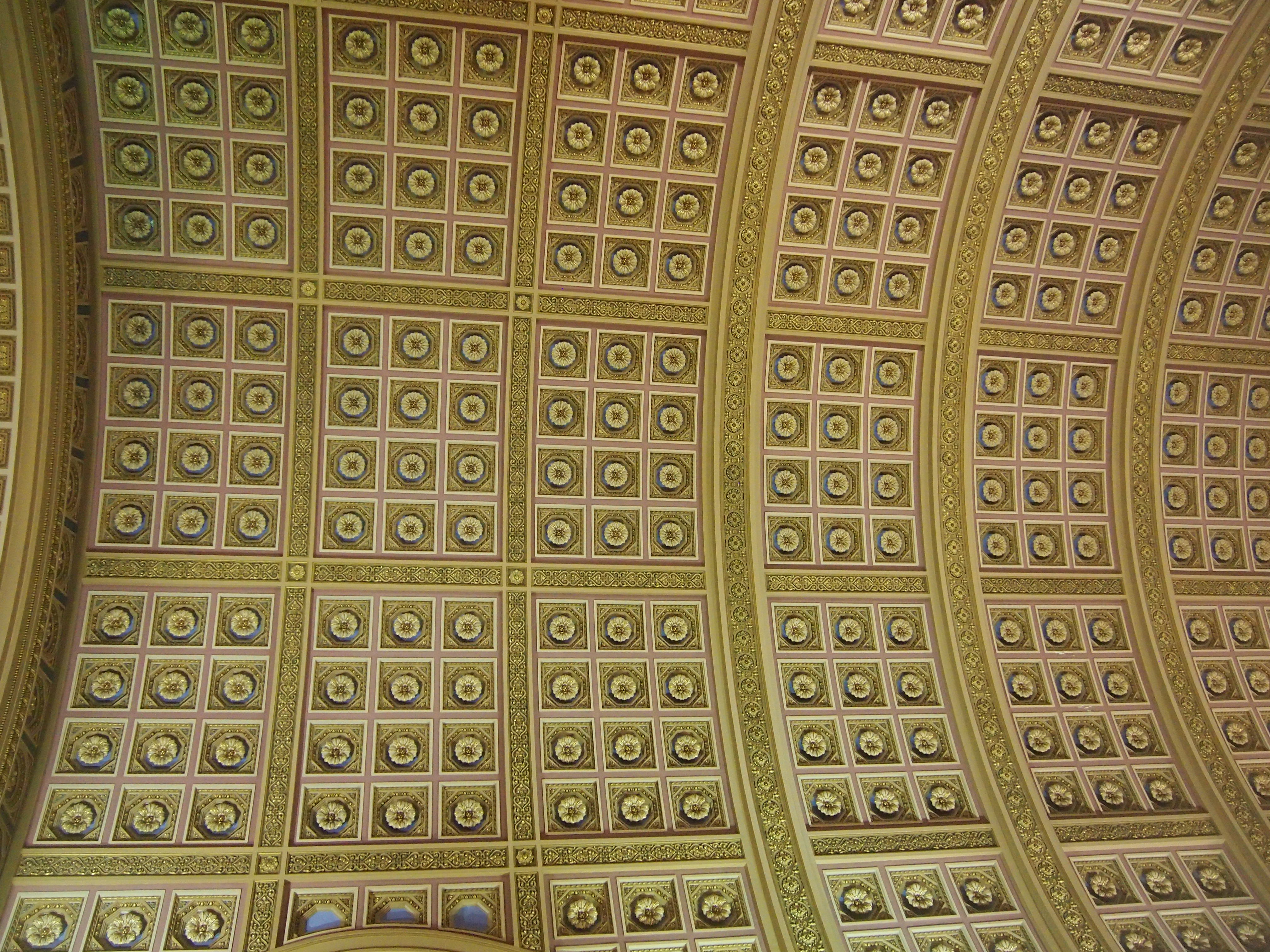

The AIA Guide to Chicago is succinct on the basilica: “It’s Bramante on the Boulevard — with a coffered, barrel-vaulted ceiling rising above the long nave. The stolid Classical facade is enlivened by an English Baroque steeple (its mate was destroyed by lightning).”

Looking straight up at that barrel-vaulted ceiling.

It’s familiar from a short scene in the 1987 movie version of The Untouchables. In our time, that’s easy to confirm. Sean Connery and Kevin Costner are toward the back of the very long nave. I didn’t remember that scene, since I haven’t seen the movie since it was new, but I read about it. The Chicago way, eh? The Federal way — busting Capone for tax evasion — proved more effective.

It’s familiar from a short scene in the 1987 movie version of The Untouchables. In our time, that’s easy to confirm. Sean Connery and Kevin Costner are toward the back of the very long nave. I didn’t remember that scene, since I haven’t seen the movie since it was new, but I read about it. The Chicago way, eh? The Federal way — busting Capone for tax evasion — proved more effective.

It occurs to me that it’s been a good year for visiting basilicas. Our Lady of Sorrows makes the fifth so far. Hasn’t been a matter of planning, it’s just worked out that way.

It occurs to me that it’s been a good year for visiting basilicas. Our Lady of Sorrows makes the fifth so far. Hasn’t been a matter of planning, it’s just worked out that way.