My afternoon at the State Fair of Texas wasn’t the eat-it-now experience that the Wisconsin State Fair was. I ate two things: a fried chocolate pie like the kind to be found near the Texas-Oklahoma border, and a cheese and jalapeño corn dog, the best corn dog I’ve had in years, maybe ever. It’s the thing to eat at the fair, which is one of the claimants for introducing the food to the world.

Mostly I looked around. I spent some time in the animal barns, for example.

I missed the pig races, but I did see some riding acrobatics.

I missed the pig races, but I did see some riding acrobatics.

I also saw a temporary exhibit at the former Museum of Nature & Science, which left Fair Park a few years ago to become the Perot Museum of Nature and Science. The exhibit was called Canstruction, featuring structures made of cans. Such as “Big Reunion,” a model of Dallas’ Reunion Tower by JHP and RLG, two Dallas architecture firms, made out of 3,064 cans — carrots, spinach, mixed vegetables, tomatoes, and beans — plus wiring and LED lights (all that info is on the sign).

I also saw a temporary exhibit at the former Museum of Nature & Science, which left Fair Park a few years ago to become the Perot Museum of Nature and Science. The exhibit was called Canstruction, featuring structures made of cans. Such as “Big Reunion,” a model of Dallas’ Reunion Tower by JHP and RLG, two Dallas architecture firms, made out of 3,064 cans — carrots, spinach, mixed vegetables, tomatoes, and beans — plus wiring and LED lights (all that info is on the sign).

I liked this one too.

I liked this one too.

“St. Basil’s Cathedral, Moscow,” by Humphreys & Partners Architects, using 2,090 cans: corn, jalapeños, tomato sauce, chilis, and mandarin oranges, among others.

“St. Basil’s Cathedral, Moscow,” by Humphreys & Partners Architects, using 2,090 cans: corn, jalapeños, tomato sauce, chilis, and mandarin oranges, among others.

I also got a good look at Fair Park itself, one of the deco marvels of the world. I’d been to the park before, but barely took the opportunity to walk around and gawk at the likes of this.

That’s the South Entrado of the Centennial Building, featuring a statue of the Republic of Texas, complete with the lone star and cotton flower. It’s part of Fair Park’s grand Esplanade, with buildings and sculpture on either side of a long reflecting pool. There are six monumental statues along the Esplanade.

That’s the South Entrado of the Centennial Building, featuring a statue of the Republic of Texas, complete with the lone star and cotton flower. It’s part of Fair Park’s grand Esplanade, with buildings and sculpture on either side of a long reflecting pool. There are six monumental statues along the Esplanade.

Fairpark.org says of the Esplanade that “the principal axis of the Texas Centennial Exposition was developed along the existing layout of the State Fair grounds. [Head architect] George Dahl strengthened the formal axis by adapting existing, unrelated State Fair exhibition halls with new, monumental facades and projecting porticos on each side of a 700-foot-long reflecting pool.

Fairpark.org says of the Esplanade that “the principal axis of the Texas Centennial Exposition was developed along the existing layout of the State Fair grounds. [Head architect] George Dahl strengthened the formal axis by adapting existing, unrelated State Fair exhibition halls with new, monumental facades and projecting porticos on each side of a 700-foot-long reflecting pool.

“The porticos establish the visual framework of the Esplanade and accentuate the grand perspective leading up to the Hall of State. Monumental artwork deftly combines with additional site features to complete the visually complex – and dramatic – spectacle.”

Each of the six statues represents the six nations that have asserted sovereignty over Texas or parts of it — what the Six Flags Over Texas refers to — namely Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the Confederacy, and the United States. France, Mexico and the U.S. were by Raoul Josset, a French sculptor (remarkable how many Euro-sculptors were active in Texas), while Spain, the Republic, and the C.S.A. were by Lawrence Tenney Stevens.

The Esplanade also featured a lot of murals, such as this bas relief mural by Pierre Bourdelle. This was one entitled “Man and Angel.” One source tells me it symbolizes air transport. It’s one of many murals along the Esplanade, each about three stories high.

At the eastern end of the pool are two large figures, the striking David Newton replicas of Lawrence Tenney Stevens’s 1936 sculptures, “The Tenor” and “The Contralto.” The originals were lost, maybe melted down for their metal during WWII, but exact replicas were created in 2009.

At the eastern end of the pool are two large figures, the striking David Newton replicas of Lawrence Tenney Stevens’s 1936 sculptures, “The Tenor” and “The Contralto.” The originals were lost, maybe melted down for their metal during WWII, but exact replicas were created in 2009.

As I was taking pictures of “The Contralto,” a group of boys came up to the statue. “Hey, is that a chick?” “Yeah, that’s a chick.” Some laughter. Yep, it’s an aluminum deco chick, companion to the aluminum deco dude nearby.

As I was taking pictures of “The Contralto,” a group of boys came up to the statue. “Hey, is that a chick?” “Yeah, that’s a chick.” Some laughter. Yep, it’s an aluminum deco chick, companion to the aluminum deco dude nearby.

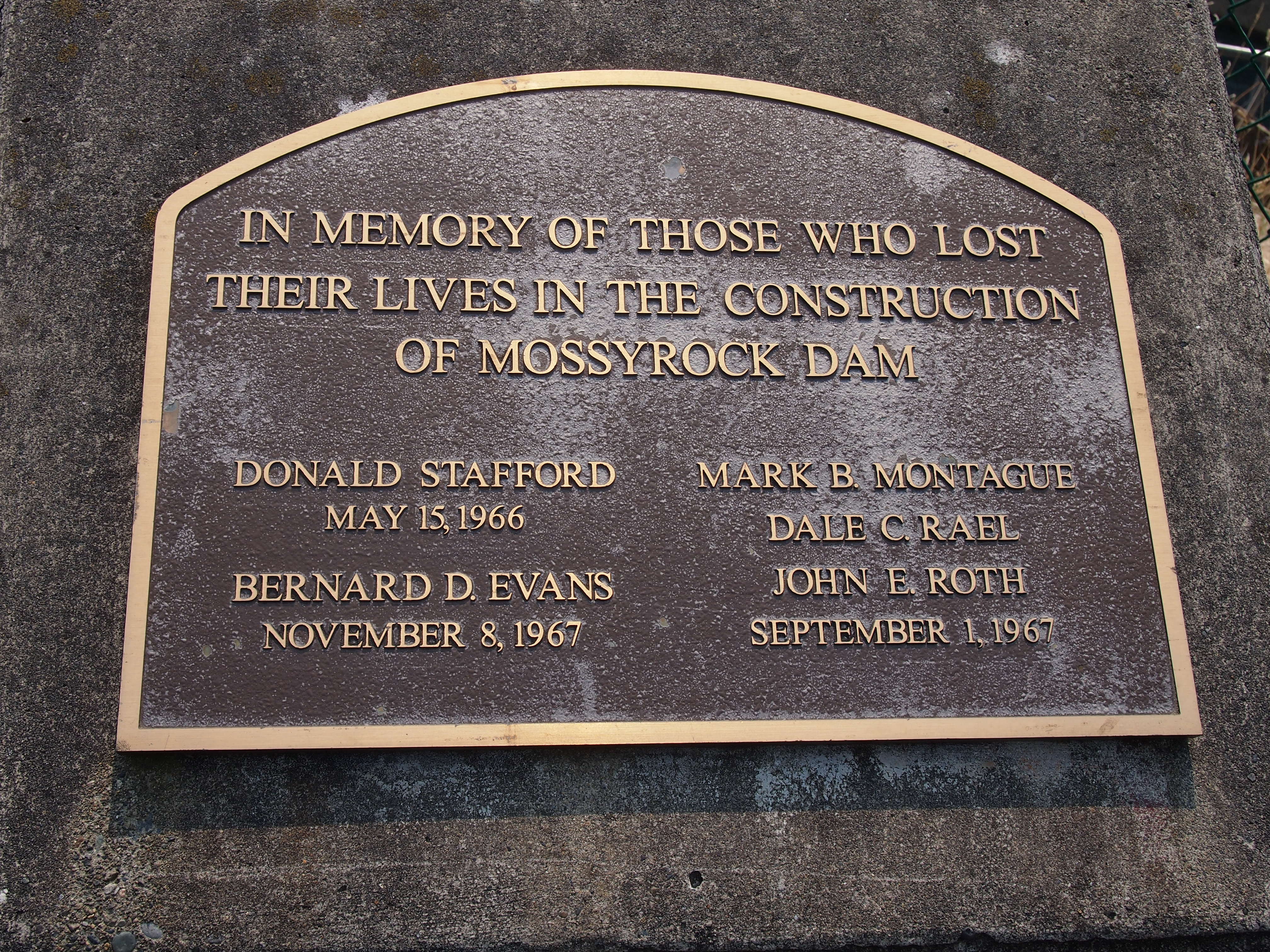

I consulted my map and picked out something else in the vicinity to see. That turned out to be Mossyrock Dam in Lewis County, Wash.

I consulted my map and picked out something else in the vicinity to see. That turned out to be Mossyrock Dam in Lewis County, Wash.