The first lines of the search results for the El Born district of Barcelona, sampled this morning:

El Born is sandwiched between Via Laietana and Barceloneta and is served by the metro stops Barceloneta and Jaume 1 which are on the same line. Las Ramblas and…

El Born brings to Greenpoint and NYC a taste of tapas y platillos from Spain and has a focus in Barcelona, where the owners are from.

A local’s guide to El Born district of Barcelona. The 26 best hotels, museums, bars, restaurants, shops and guided tours of El Borne for 2023.

Located in between the Gothic Quarter and the Ciutadella Park, El Born is one of Barcelona’s trendiest and most popular neighborhoods.

Once home to Barcelona’s affluent merchants, noblemen, and artisans, El Born is now one of the hippest, liveliest, and most creative…

That last line is from a site called “travel away” (no caps), which looks like an Afar knockoff, and the headline is “A Curated Guide to El Born, Barcelona.” Of course it’s curated. You must visit that perfect tapas place that serves unique craft sangria, or you’ll come down with a bad case of FOMO. (We had tasty tapas and swell sangria during our Catalonia holiday, but not in El Born.)

Anyway, you can’t just wander around to see what you can see, can you?

Of course you can. I wasn’t hip enough to know that El Born is trendy, but we were intrigued by our surroundings as we ambled along the mostly pedestrian thoroughfare Passeig del Born, where we acquired a drink and snacks to eat on a bench.

The soda in question. All the way from Hamburg. We’d never heard of it, so we gave it a go. Now I can’t remember what it tasted like, so it must have been neither that good or particularly bad.

At one end of the passeig is a large plaza featuring an imposing cast-iron structure.

That’s El Born Centre de Cultura i Memoria. The main part of the inside was free to walk into; just follow the rules.

The El Born Centre was once a large public market (Mercat del Born), and the first cast-iron structure of its kind in Barcelona, dating from 1876.

I was inspired to take a few black-and-whites.

I should have take more of those in Barcelona, which has a lot of good contour for monochrome. Ah, well. The iron framework over our heads wasn’t the only thing to see at El Born Centre. Beneath the ground-floor walkways is an archaeological site with a connection to Barcelona’s bloody past.

A neighborhood once existed here, as it becomes clear staring down on the ragged wall stubs and stones. In 1714, after the Principality of Catalonia capitulated to Bourbon forces toward the end of the War of Spanish Succession, the victors leveled the neighborhood to build the Ciutadella (citadel) and its security esplanade, presumably to help keep the Catalans in line. Well over a century later, after the hubbub in ’68 (1868, that is) the city assumed control of the site and eventually built the market on a relatively small part of it.

Much later, the ruins were uncovered, and archaeological investigations proceed. Sources tell me the ruins of 60 houses in 11 separate blocks can be found in El Born’s archaeological site.

We exited from the opposite end of El Born Centre that we entered, and from there a short street leads to the sizable Parc de la Ciutadella (Citadel Park), which is the use 19th-century Barcelona had for most the former military facility. Good choice. It’s a grand place for a stroll. Or just to hang out.

A water feature. Reminded me a little of Chapultepec Park in Mexico City.

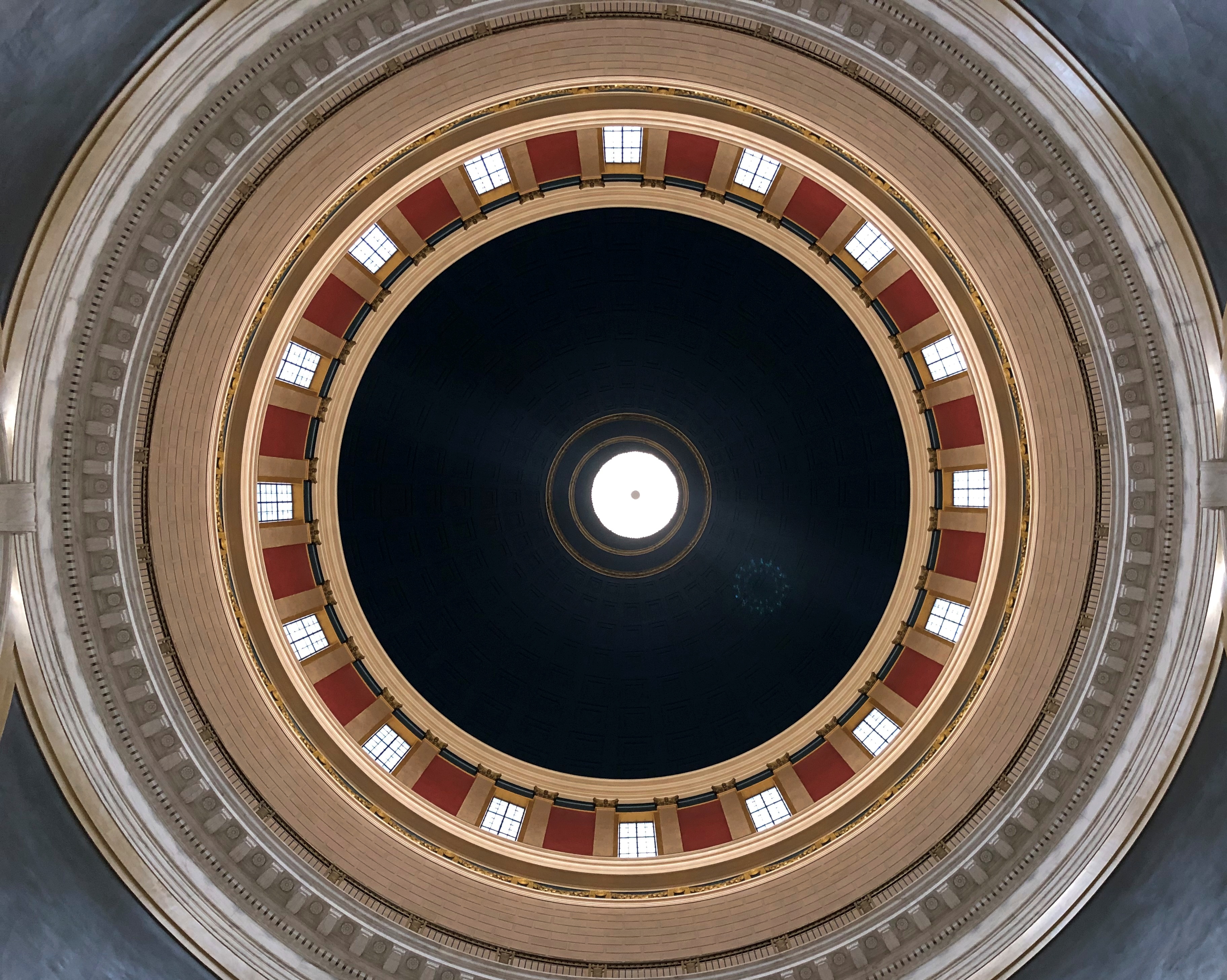

Plus an assortment of monumental structures. Such as the Catalonian parliament building.

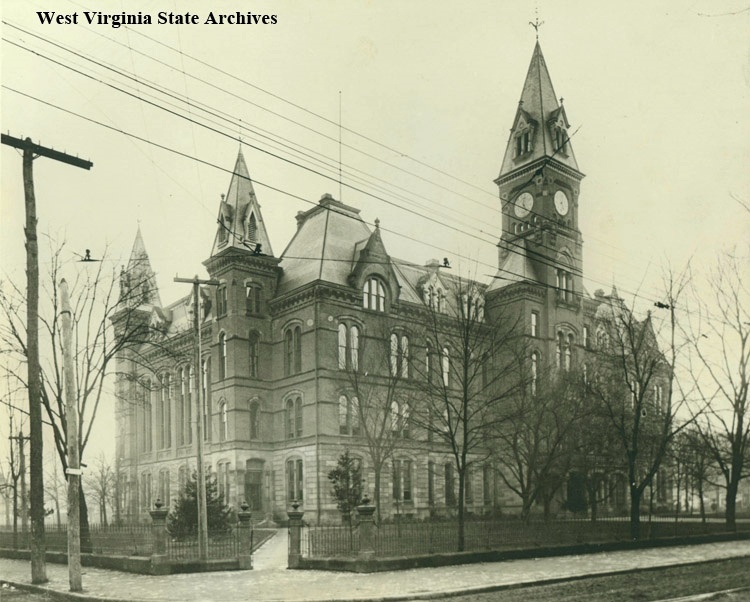

A thing called Castell dels tres Dragones, which seemed to be closed for repairs. Later (as in, today) I learned that Lluís Domènech i Montaner designed it. We’ll come back to him. He did something much more amazing that we saw later.

A Catalan gazebo. Note the difference in detail from Castilian gazebos. Catalans are reportedly fiercely proud of their gazebo heritage.

We were too tired to climb these stairs, but we did admire the work from some distance.

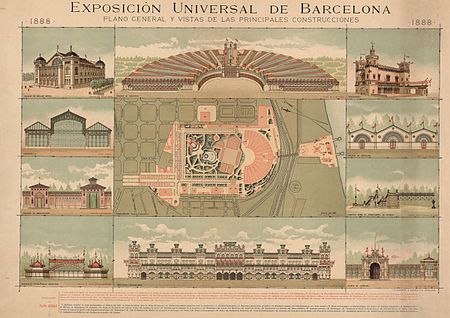

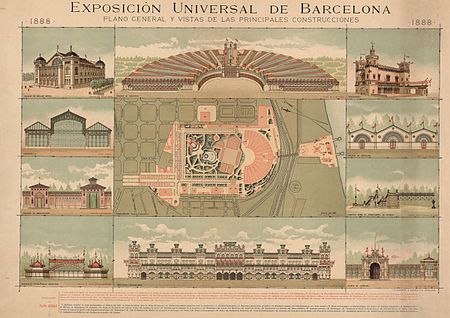

That’s the Ciudadela Park Cascade, which as far as I can tell doesn’t honor anything specific, but was built in the late 19th century to celebrate Barcelona’s revival. And in time for the Universal Exhibition of Barcelona in 1888, which is yet another place to visit once that time machine is up and running (and 1929, too).

The park, like Jackson Park in Chicago and Hemisfair is San Antonio, owes much of its modern shape to a long-ago world’s fair.