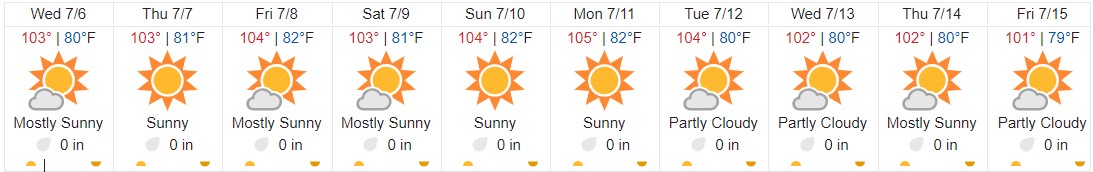

Ah, high summer.

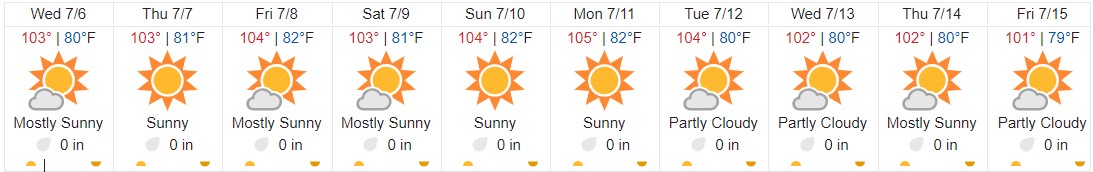

That’s in Dallas. I’m not there. Today’s high here was 79 F., a dip from a hot and muggy 90s-day on Tuesday. Several degrees of latitude will make that difference.

One of these days, the times might catch up with Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne, leader in the Revolution and scourge of the Northwest Territory Indians, but for now, you can find him on horseback in bronze at Freimann Square in downtown Fort Wayne, Indiana, in a work by Chicagoan George Etienne Ganiere (1865-1935).

We gazed a Mad Anthony for a few moments as part of our trip through northern Indiana. I wanted to take a short trip over the long Independence Day weekend, but I didn’t want it to consume the entire three days.

So on Saturday, we left in mid-morning and made our way to Fort Wayne, where we stayed overnight. On Sunday, we returned across northern Indiana to get home, which took up most of the day.

We arrived in Nappanee, Indiana, for lunch on Saturday. I’m glad to report that Main Street Roasters (not so new anymore, it seems) makes a fine pulled pork sandwich. Yuriko said the ingredients in her Cobb salad tasted very fresh, and I sampled some, and agreed. The place was doing a brisk business.

We figured the main source for both fresh pork and fresh greens was the Amish farms in the area. Nappanee is considered the focus of one of the country’s larger Amish populations, though that’s a little hard to tell in a casual look around downtown, which isn’t so different from other Indiana towns its size (pop. nearly 7,000). Out away from town, though, you can see from the road farm houses and other buildings, clustered closer than in other rural areas, which is characteristic of Amish settlements.

In town, Plain People in carriages rolled by now and then. Some female store clerks wore the small head coverings common among Mennonites. The Amish tourist attraction in Nappanee known as Amish Acres closed in late 2019, and a more upmarket property re-opened the next year — in an example of bad timing, though it seems to have survived — as The Barns at Nappanee, Home of Amish Acres. Maybe all those extra words are going to cost you more.

Across the street from Main Street Roasters (and not Amish Acres).

On Sunday, our first brief stop was at Magic Wand, home of the Magicburger, which can be found in Churubusco, Indiana.

We didn’t have a magic burger, but rather shared a strawberry milkshake to go. Among strawberry milkshakes, it was the real deal. The real tasty deal, straw-quaffed as we speed along U.S. 33.

Churubusco was a name I took an instant liking to. The town fathers apparently read in their newspapers about the battle of that name, and wanted the town to borrow a bit of its martial glory. According to some sources, it gets shortened in our time, and maybe for a long time, to Busco. I also noticed references to the place, on signs and the like, as Turtletown. Really? What was that about? I wondered.

The Beast of Busco, that’s what. Quite a story. A giant among turtles that the townsfolk never could quite capture. I haven’t had this much fun reading hyperlocal history — lore — since I chanced across a small lake in Wisconsin that is supposedly home to an underwater pyramid. Turtle Days was last month.

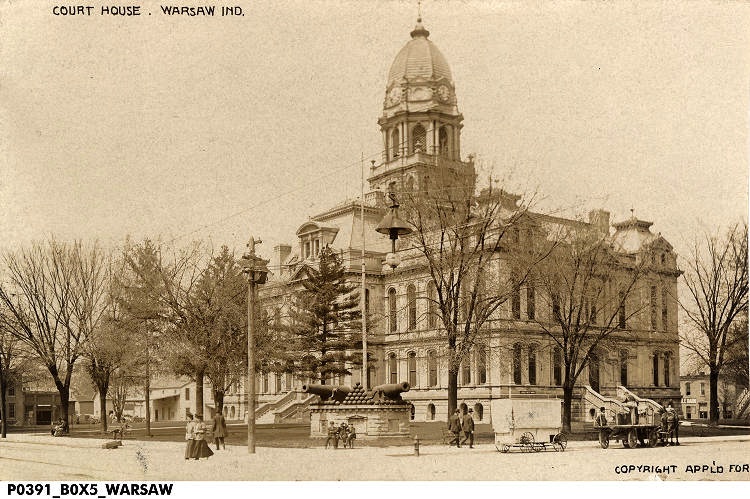

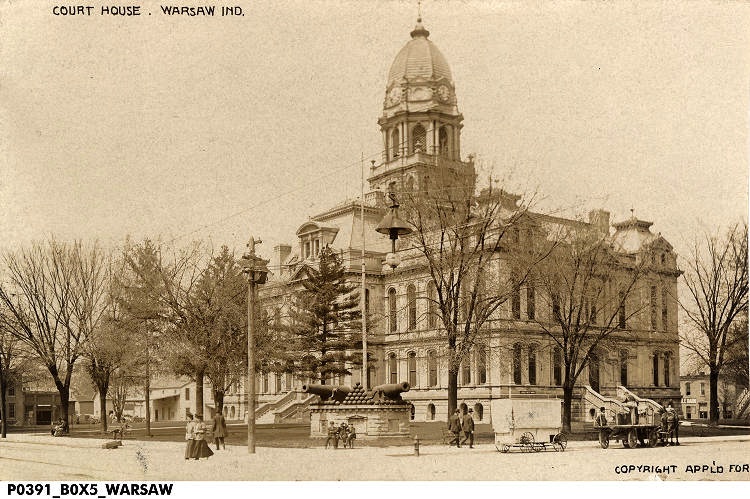

Another spot for a short visit on Sunday: Warsaw, Indiana. It’s the seat of Kosciusko County, with a handsome Second Empire courthouse rising in the town square.

Designed in the 1880s by Thomas J. Tolan, who died during construction, the Indiana Historical Society says. The project was completed by his son, Brentwood S. Tolan.

The square sports some other handsome buildings, too.

Warsaw is also home to a garden the likes of which I’d never imagined, and the reason I stopped in town, days after spotting it on Google Maps and then looking it up: the Warsaw Biblical Gardens.

The brainchild of a local woman back in the 1980s with access to the land. “It would be no ordinary garden — not a rock garden, nor a rose garden, nor a perennial garden — it would be a truly unique and beautiful Biblical Garden,” the garden’s web site says.

“Actually, we say ‘gardens’ because the Warsaw Biblical Gardens has a variety of areas: the Forest, Brook, Meadow, Desert, Crop and Herb gardens; the Grape Arbor; and the Gathering site. Warsaw Biblical Gardens is ¾-acre in size, and there are very few gardens like this in the United States.

“The term ‘biblical’ refers mainly to the fact that the plants, trees, flowers, herbs, etc., are mentioned in the Old and/or New Testaments of the Bible. These have been carefully researched to preserve the integrity of the Gardens’ uniqueness.

“The Warsaw/Winona Lake area of Indiana has a long religious history. That history begins perhaps with the Chatauqua times of Winona Lake, now being revived. [Really?] Many other famous historical religious figures made their home’s here, from Homer Rodeheaver to Fanny Crosby to Billy Sunday.”

I won’t pretend I didn’t have to look up the first two of those three. Regardless, it’s a stunning little place.

Go far — always good if you can manage it. But also go near.