Pershing Square in downtown Los Angeles looks like a pleasant public space, but on the morning of February 22, I only got the barest glimpse. Entry to the park had been blocked all the way around by temporary barricades. This was a concern, since according to the receipt for the walking tour of downtown LA that I’d booked for that morning, the group was supposed to meet at Pershing Square.

Soon I found that we were meeting at the corner of W. 6th St. and S. Olive St., at the edge of the park, with the tour proceeding from there. I wasn’t the only one who asked the guide what was going on at Pershing Square. Turns out the city had rented it for the weekend for a couple of Insane Clown Posse concerts, the second of which would be that evening. Sounded like a must-miss to me.

The tour took us on foot past, and sometimes through, 12 different historic structures in downtown Los Angeles, beginning with the Millennium Biltmore Hotel. This is the central wing of the building.

Originally the Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel when completed in 1923, the property has 683 rooms, down from about 1,500 at its opening. People didn’t mind smaller rooms in those days.

Originally the Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel when completed in 1923, the property has 683 rooms, down from about 1,500 at its opening. People didn’t mind smaller rooms in those days.

The south wing.

Design by Schultze & Weaver, a New York firm best known for the Waldorf-Astoria in Manhattan, though that would come later.

Design by Schultze & Weaver, a New York firm best known for the Waldorf-Astoria in Manhattan, though that would come later.

The north wing. Why fly the Singapore flag, I don’t know. Owner Millennium & Copthorne Hotels plc is based in London.

Not far away is the CalEdison Building, one of LA’s grand art deco exercises, designed by Allison & Allison and finished in 1931.

The allegory above the entrance holds a torch. Not a torch of fire, but capped with a light bulb, though the electric utility that used to anchor the building left nearly 50 years ago.

The allegory above the entrance holds a torch. Not a torch of fire, but capped with a light bulb, though the electric utility that used to anchor the building left nearly 50 years ago.

The exterior is grand, but the main lobby is the real wow.

The exterior is grand, but the main lobby is the real wow.

More CalEdison pictures are here.

More CalEdison pictures are here.

Speaking of wow, the Los Angeles Central Library came a little further on the tour. Along with the U.S. and California flags flying there is the flag of the city of Los Angeles. The library is capped with an ornate pyramid. Originally it was supposed to be a dome, but 1920s Egyptmania had its influence on the building.

Completed in 1926 with a design by Bertram Goodhue and Carlton Winslow, what nearly happened to the library about 50 years later? Demolition. The Los Angeles Conservancy was organized at that time in response, and the building was saved.

Completed in 1926 with a design by Bertram Goodhue and Carlton Winslow, what nearly happened to the library about 50 years later? Demolition. The Los Angeles Conservancy was organized at that time in response, and the building was saved.

Only to nearly burn down in April 1986. The cause remains a mystery. Our guide asked those of us old enough — which was most of the group — whether we remembered the fire. I drew a blank. Even living in Nashville at the time, I must have heard about it, but I couldn’t remember.

“It happened three days after the Chernobyl disaster, so it didn’t get as much coverage as it might have otherwise,” she said. Such is the news cycle.

The citizens of LA insisted that the library be rebuilt, and it was. Such places as the splendid central rotunda were thus saved again.

Looking up in the rotunda.

On the rotunda walls are fine California history murals, finished in 1933 by artist Dean Cornwell.

On the rotunda walls are fine California history murals, finished in 1933 by artist Dean Cornwell.

Across the street from the library are the Bunker Hill Steps, designed by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin and completed in 1990.

Across the street from the library are the Bunker Hill Steps, designed by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin and completed in 1990.

If I knew downtown Los Angeles had a topographical feature called Bunker Hill, I’d forgotten it. The place has quite a history: a posh neighborhood in the late 19th century, a run-down one by the mid-20th century, and then the victim of urban renewal. These days, office towers and other commercial buildings developed during or after the 1980s occupy most of Bunker Hill.

If I knew downtown Los Angeles had a topographical feature called Bunker Hill, I’d forgotten it. The place has quite a history: a posh neighborhood in the late 19th century, a run-down one by the mid-20th century, and then the victim of urban renewal. These days, office towers and other commercial buildings developed during or after the 1980s occupy most of Bunker Hill.

Once you go up a hill, you have to go back down again, or at least we did to reach the next destinations on the tour. So we took Angels Flight Railway down the side of Bunker Hill. This is the terminal at the top.

The original funicular, which opened in 1901, closed in 1969, lost temporarily to urban renewal. The line was revived in 1996 a block south of the original location, though it has spent much of the last quarter-century closed because of safety problems. With any luck, those are resolved now.

Looking up the track, which is nearly 300 feet long.

The terminal at the bottom.

The terminal at the bottom.

The last place on the tour: The Bradbury Building. I knew it by reputation. A lot of people know it that way. If it were in, say, Des Moines, that wouldn’t be true. But it’s in Los Angeles.

The last place on the tour: The Bradbury Building. I knew it by reputation. A lot of people know it that way. If it were in, say, Des Moines, that wouldn’t be true. But it’s in Los Angeles.

The exterior is nice, but it’s the striking interior that makes it a favorite of location scouts and tourists. An almost exact contemporary of the 1890s Monadnock Building in Chicago, the Bradbury’s superb ironwork reminded me of that building.

The exterior is nice, but it’s the striking interior that makes it a favorite of location scouts and tourists. An almost exact contemporary of the 1890s Monadnock Building in Chicago, the Bradbury’s superb ironwork reminded me of that building.

One George Wyman, a draftsman without formal architectural training, designed the building, at least according to most sources. He was inspired by the description of a building in Looking Backwards by Edward Bellamy, again according to most sources. I like to believe the stories are true, since they argue against credentialism.

One George Wyman, a draftsman without formal architectural training, designed the building, at least according to most sources. He was inspired by the description of a building in Looking Backwards by Edward Bellamy, again according to most sources. I like to believe the stories are true, since they argue against credentialism.

Back to Insane Clown Posse. I didn’t actually have a brush with them or any Juggalos closer than a few blocks away. That evening, as I headed for the Metro station to leave downtown, I heard the concert off in the distance. It was probably one of the opening acts, but no matter. I could hear that it was loud.

Whatever else you can say about Frank Gehry, his designs aren’t like their surroundings. They’re going to stand out. Also, they’re interesting to stand under.

Whatever else you can say about Frank Gehry, his designs aren’t like their surroundings. They’re going to stand out. Also, they’re interesting to stand under. I’d read that self-guided tours of the venue were free, and that’s true. You get an MP3 player at a table just inside the Hope St. entrance, and off you go. The audio snippets about the development of the building, along with various design elements, are narrated by John Lithgow, with some additional commentary by those who worked on the project, including Gehry.

I’d read that self-guided tours of the venue were free, and that’s true. You get an MP3 player at a table just inside the Hope St. entrance, and off you go. The audio snippets about the development of the building, along with various design elements, are narrated by John Lithgow, with some additional commentary by those who worked on the project, including Gehry. Still, the rest of the interior was worth a look.

Still, the rest of the interior was worth a look. Though it’s invisible from the street, the hall has some outside space at mid-level, including greenery. A pleasant interlude among the twists of metal and vaulting ceilings.

Though it’s invisible from the street, the hall has some outside space at mid-level, including greenery. A pleasant interlude among the twists of metal and vaulting ceilings. At one point, the outdoor space practically becomes a box canyon made of metal.

At one point, the outdoor space practically becomes a box canyon made of metal.

Later that day, I visited The Broad, which is next door to Disney, though much newer, completed less than five years ago.

Later that day, I visited The Broad, which is next door to Disney, though much newer, completed less than five years ago. Interesting texture for a 120,000-square-foot box. It looks good, but how long will it be until its gleaming exterior begins to turn gray and streaky? Eventually, but I won’t worry about it. That will be on designer Diller Scofidio + Renfro, who did The Broad in collaboration with Gensler.

Interesting texture for a 120,000-square-foot box. It looks good, but how long will it be until its gleaming exterior begins to turn gray and streaky? Eventually, but I won’t worry about it. That will be on designer Diller Scofidio + Renfro, who did The Broad in collaboration with Gensler.

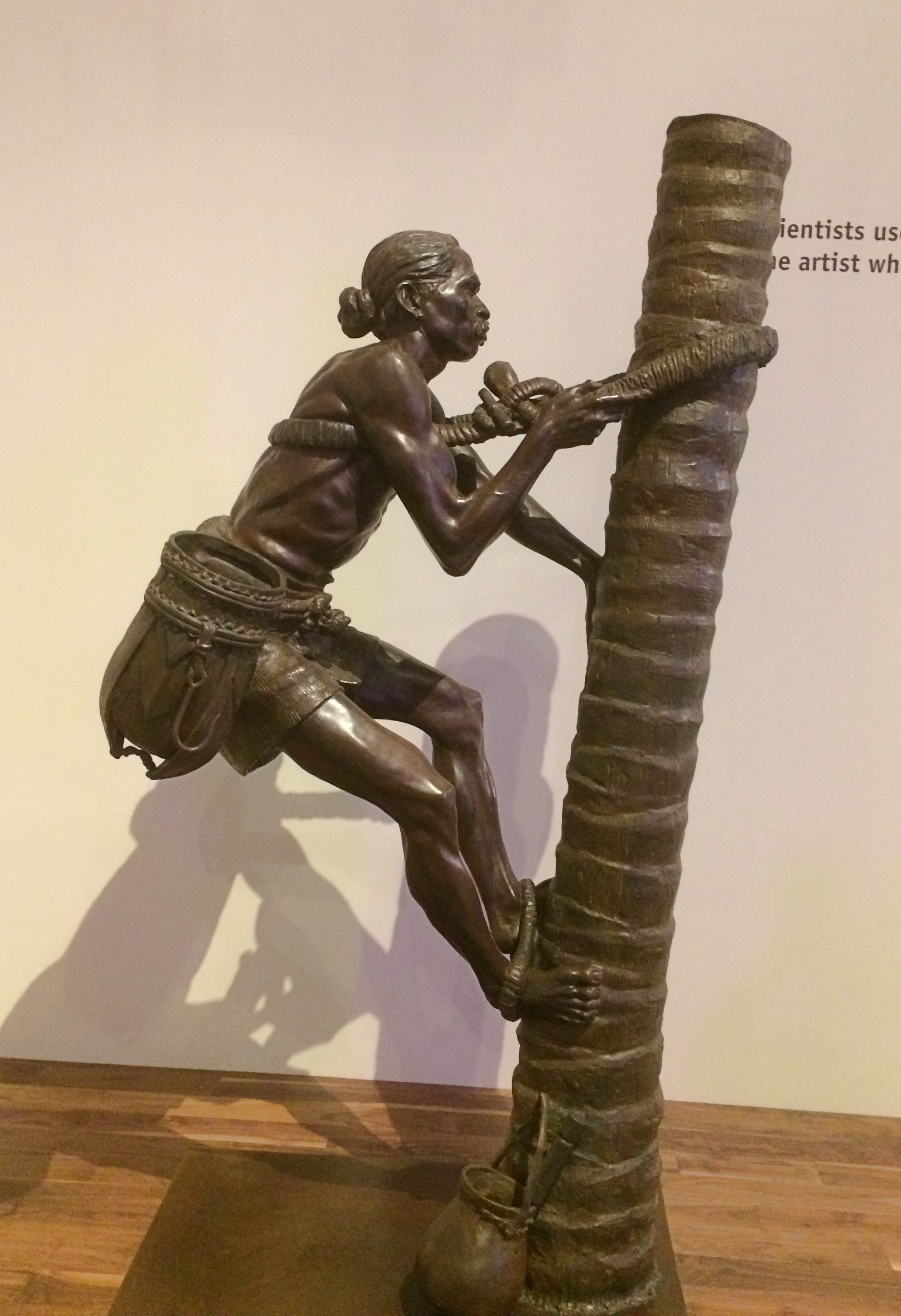

After the main hall, we spent time at the Granger Hall of Gems, the Malott Hall of Jades and at a display of meteorites. Last time I visited the museum, we were promised that there would soon be a permanent exhibit of pieces of the Chelyabinsk Meteor,

After the main hall, we spent time at the Granger Hall of Gems, the Malott Hall of Jades and at a display of meteorites. Last time I visited the museum, we were promised that there would soon be a permanent exhibit of pieces of the Chelyabinsk Meteor,

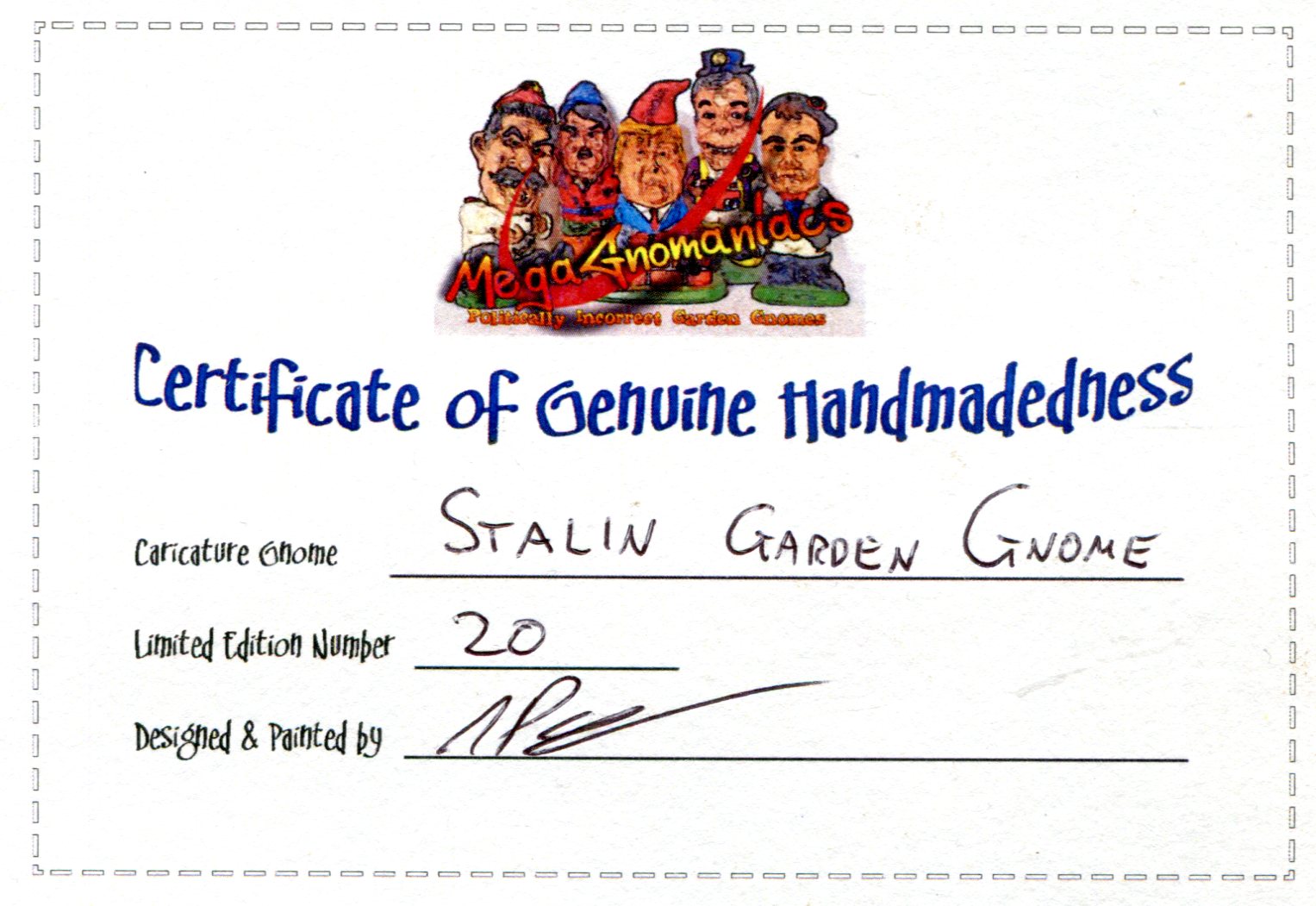

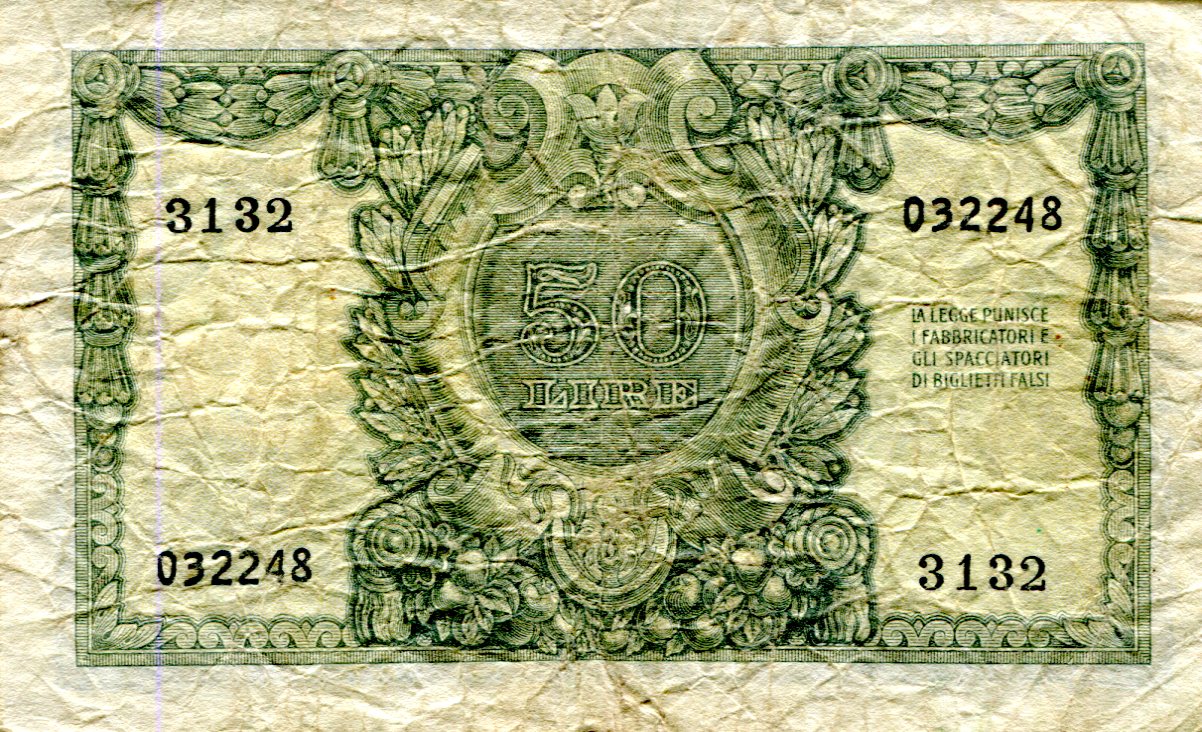

The note is also small in size. Interestingly, exactly four inches long and two-and-a-half inches tall. Odd, I would have thought that the sides measure evenly in centimeters rather than inches.

The note is also small in size. Interestingly, exactly four inches long and two-and-a-half inches tall. Odd, I would have thought that the sides measure evenly in centimeters rather than inches. Who are these gentlemen who look so much alike, except the eyes of one are closer together than the other?

Who are these gentlemen who look so much alike, except the eyes of one are closer together than the other?