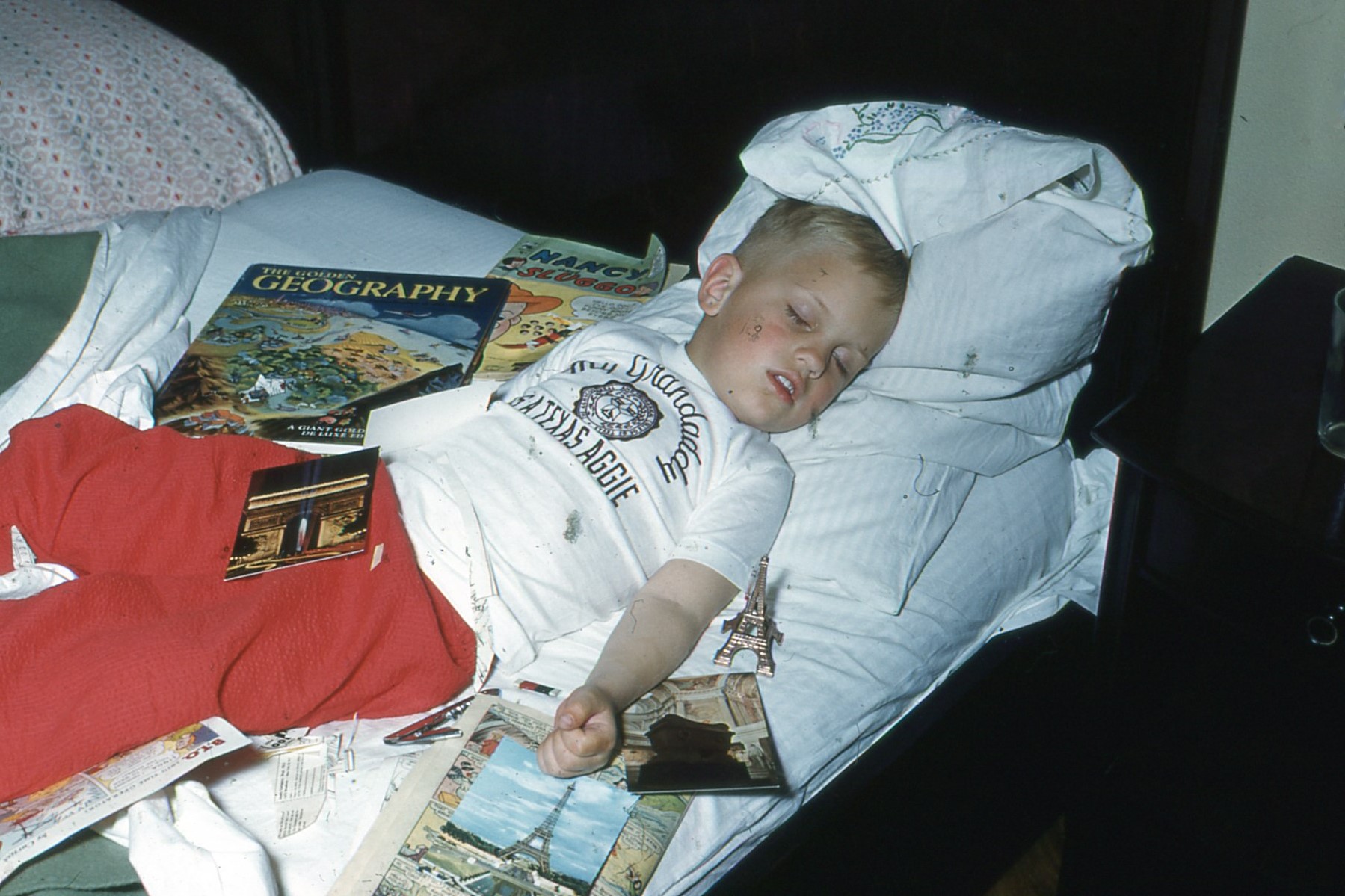

On January 1, I picked up A.J. Liebling’s Between Meals, subtitled “An Appetite for Paris,” which is a 1959 collection of essays about his eating experiences in that city and other parts of France, which were vast and diverse, beginning in the 1920s. It’s an immensely charming work, not just about the food and drink he encountered, but also with bits about other gastronomes, life as an expat, technically as a student in Paris, boxing — he wrote a lot about that elsewhere — and other asides.

It’s a somewhat different expat-Paris-in-the-20s than Hemingway’s. For Liebling, eating and drinking were the point, and not just in the context of hanging out with other expats (Liebling seemed to eat alone a lot). Hemingway drank a lot, of course, because That’s What Men Do, but for Liebling his “feeding” — his term — was purely aesthetic. In France he found a lifelong devotion to being a gastronome, and by the time he died in 1963, at 59, it had made him very fat.

I doubt that he regretted it. In Between Meals he writes: “Mens sano in corpore sano is a contradiction in terms, the fantasy of a Mr. Have-your-cake-and-eat-it. No sane man can afford to dispense with the debilitating pleasures; no ascetic can be considered reliably sane. Hitler was the archetype of the abstemious man. When the other krauts saw him drinking water in the Beer Hall they should have known he was not to be trusted.”

You’d thinking eating to excess in Jazz Age Paris would be enough for any man, but Liebling asserts that Belle Époque gastronomes had it better: “In the heroic age before the First World War, there were men and women who ate, in addition to a whacking lunch and a glorious dinner, a voluminous souper after the theater or the other amusements of the evening. I have known some of the survivors, octogenarians of unblemished appetite and unfailing good humor — spry, wry, and free of the ulcers that come from worrying about a balanced diet….

“One of the last of the great round-the-clock gastronomes of France was Yves Mirande, a small, merry author of farces and musical comedy books [1875-1957]. In 1955… Mirande would dazzle his juniors, French and American, by dispatching a lunch of raw Bayonne ham and fresh figs, a hot sausage in crust, spindles of filleted pike in a rich rose sauce Nantua, a leg of lamb larded with anchovies, artichokes on a pedestal of foie gras, and four or five kinds of cheese, with a good bottle of Borbeaux and one of champagne, after which he would call for the Armagnac and remind Madame to have ready for dinner the larks and ortolans she had promised him, with a few langoustes and a turbot — and, of course, a fine civet made from marcassin, or young wild boar, that the lover of the young leading lady in his current production had sent up from his estate in the Sologne…”

Liebling also touched on another puzzling phenomenon, in the context of eating, but which applies to other things. Namely, why wealth often seems to narrow, rather than broaden, experience: “A man who is rich in his adolescence is almost doomed to be a dilettante at table. This is not because all millionaires are stupid but because they are not impelled to experiment. In learning to eat, as in psychoanalysis, the customer, in order to profit, must be sensible of the cost.”