Heading out from San Antonio on U.S. 90, I considered a stop in Uvalde, Texas, to see the Briscoe-Garner Museum. Briscoe, as in Dolph Briscoe, 41st governor of Texas (in the 1970s, so I remember him), whose family owned 560,000 acres of Texas land not long after his death in 2010. That’s about 875 square miles, or about two-thirds the size of Rhode Island, and not a lot smaller than the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

Garner, as in Cactus Jack Garner, 39th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and 32nd Vice President of the United States, who famously said the vice presidency wasn’t “worth a bucket of warm piss.” Especially when you end up at odds with your president. So far he’s the longest-lived vice president or president in United States history, and, as some anonymous writer at Wiki points out, had the distinction of living during the presidencies of both Johnsons: Andrew and Lyndon.

Enough there for a pretty good museum, I’d say. But as I stopped at a rest area along U.S. 90, I did a little more checking and found that the museum is closed on Mondays.

So I decided to drop by Uvalde Cemetery and find Garner’s grave. It’s a large burial ground, marked by some trees and greenery, but not overly garden-like.

Still, I figured I could find Garner. There would probably be flag poles near him. So there were.

Still, I figured I could find Garner. There would probably be flag poles near him. So there were.

Here’s the grave of John Nance Garner and his wife Marietta Rheiner Garner. Imagine that, he was a fully grown man at the turn of the 20th century, and yet lived to see men travel into space.

Here’s the grave of John Nance Garner and his wife Marietta Rheiner Garner. Imagine that, he was a fully grown man at the turn of the 20th century, and yet lived to see men travel into space.

How many vice presidential graves have I seen? That is, the resting places of men who were never also president? Only one other that I can think of. I got a look from some distance at the stone of John C. Calhoun in Charleston. I need to seek more of them out.

How many vice presidential graves have I seen? That is, the resting places of men who were never also president? Only one other that I can think of. I got a look from some distance at the stone of John C. Calhoun in Charleston. I need to seek more of them out.

In Fort Davis, Texas, after visiting the National Historic Site of that name, I dropped by the Jeff Davis County Library to check my email, and found it to be a fine adaptive reuse of a late 19th-, early 20-century building complex that had once been a general store, post office, an early telephone exchange and other things.

Just off Texas 118 in Fort Davis is a sign that says Pioneer Cemetery. I had to take a look at that. A narrow path, completely surrounded by the kind of diamond wire-mesh fence that you might see in any suburb, led to the cemetery gate. That was the only entrance that I saw, and otherwise the cemetery grounds were surrounded by fenced-off private houses. That felt a little odd at first, but soon I got used to it.

Like the region, the cemetery is sparsely settled.

But there are a few headstones and fenced-off plots.

But there are a few headstones and fenced-off plots.

One old soldier that I could see, Joseph Granger, CSA.

One old soldier that I could see, Joseph Granger, CSA.

According to the plaque at the entrance, the cemetery was active from the 1870s to 1914, which also says that immigrants named Dutchover are buried here, along with a madwoman and a couple of horse thieves. Sounds like a motley mix of pioneers, all right. Here are some Dutchovers.

Marfa, Texas, famed among the glitterati these days, still looks a lot like a small West Texas town, though with galleries, tony hotels and Manhattan-priced shops thrown in the mix. Unfortunately, after visiting the McDonald Observatory and Fort Davis, I didn’t have the time or energy to visit the sizable Chinati Foundation in Marfa, which I’m sure is a worthwhile destination.

Marfa, Texas, famed among the glitterati these days, still looks a lot like a small West Texas town, though with galleries, tony hotels and Manhattan-priced shops thrown in the mix. Unfortunately, after visiting the McDonald Observatory and Fort Davis, I didn’t have the time or energy to visit the sizable Chinati Foundation in Marfa, which I’m sure is a worthwhile destination.

I did look around at some other spots. The Presidio County Courthouse is handsome, for one thing.

The Hotel Paisano is decidedly handsome, too.

The Hotel Paisano is decidedly handsome, too.

Before I left Marfa, I stopped at Cementerio de la Merced, a desert cemetery with a mix of wooden markers and more formal stones. Bet not many of the glitterati pause there to pay their respects.

Before I left Marfa, I stopped at Cementerio de la Merced, a desert cemetery with a mix of wooden markers and more formal stones. Bet not many of the glitterati pause there to pay their respects.

The names on the graves are largely, but not completely, Hispanic in origin. Not far away, but separated by a fence, was a graveyard mostly of formal stones, and Anglo names.

The names on the graves are largely, but not completely, Hispanic in origin. Not far away, but separated by a fence, was a graveyard mostly of formal stones, and Anglo names.

Marfa Public Radio had this to say: “One cemetery is known as the Anglo cemetery. The other two — Cementerio de la Merced and the Marfa Catholic cemetery — are Hispanic…

” ‘Well, it was not legally segregated, but it was segregated by custom,’ says historian Lonn Taylor, a former curator at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC…

“In this part of Texas, Hispanics hold many key political offices. Yet a visible reminder of historic inequality are the cemeteries, where in death, people remain divided.”

Near the main entrance, I saw this wood carving.

Near the main entrance, I saw this wood carving.

We soon came to the highest point in the cemetery, and in fact in Brooklyn, called Battle Hill for its part in a bloody episode in the Battle of Long Island (a.k.a. the Battle of Brooklyn) in the Revolution.

We soon came to the highest point in the cemetery, and in fact in Brooklyn, called Battle Hill for its part in a bloody episode in the Battle of Long Island (a.k.a. the Battle of Brooklyn) in the Revolution. On a clear day, you can see the Statue of Liberty from Minerva’s perch, but we didn’t have a clear day. I understand that that particular the sightline is protected by law, like views of the capitol in Austin.

On a clear day, you can see the Statue of Liberty from Minerva’s perch, but we didn’t have a clear day. I understand that that particular the sightline is protected by law, like views of the capitol in Austin.

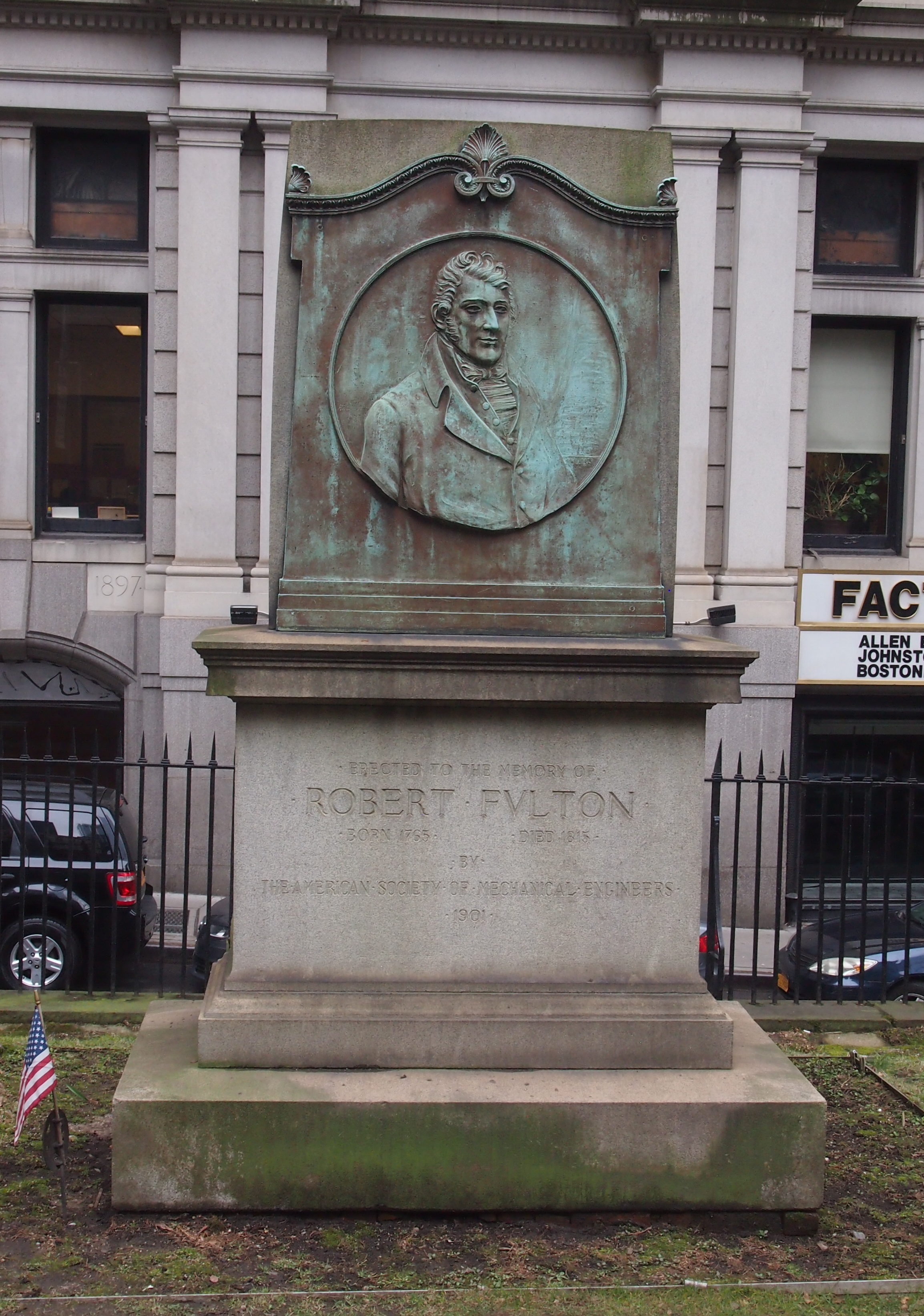

I have to admit that I either didn’t know, or had forgotten, that he is buried at Trinity. In a way, that was a good thing, since it was a nice surprise.

I have to admit that I either didn’t know, or had forgotten, that he is buried at Trinity. In a way, that was a good thing, since it was a nice surprise.