With a name like Hollywood Forever Cemetery, I suspected — in spite of what I’d read — that the place had gotten the Hollywood treatment instead of a proper renovation. That is, superficial and unsatisfying.

Fortunately, I was wrong. Just off a dowdy selection of Santa Monica Blvd., Hollywood Forever is a resplendent cemetery, on par with any of the lush rural-cemetery-movement grounds I’ve seen in other parts of the country.

With examples of funerary art.

A number of private mausoleums.

A number of private mausoleums.

Including one picturesquely set on a small island, the tomb of William A. Clark Jr. (1877-1934), son of copper baron Sen. William A. Clark Sr.

Including one picturesquely set on a small island, the tomb of William A. Clark Jr. (1877-1934), son of copper baron Sen. William A. Clark Sr.

Plenty of trees.

If you find just the right spot, you can see the Hollywood sign off in the distance.

If you find just the right spot, you can see the Hollywood sign off in the distance.

There are a few unexpected features, such as a section devoted to Southeast Asian memorials.

There are a few unexpected features, such as a section devoted to Southeast Asian memorials.

I’ve also read that in our time, Russian immigrants are fond of the cemetery. There’s plenty of visible evidence of that.

I’ve also read that in our time, Russian immigrants are fond of the cemetery. There’s plenty of visible evidence of that.

Along with a sprinkling of earlier Russian émigrés.

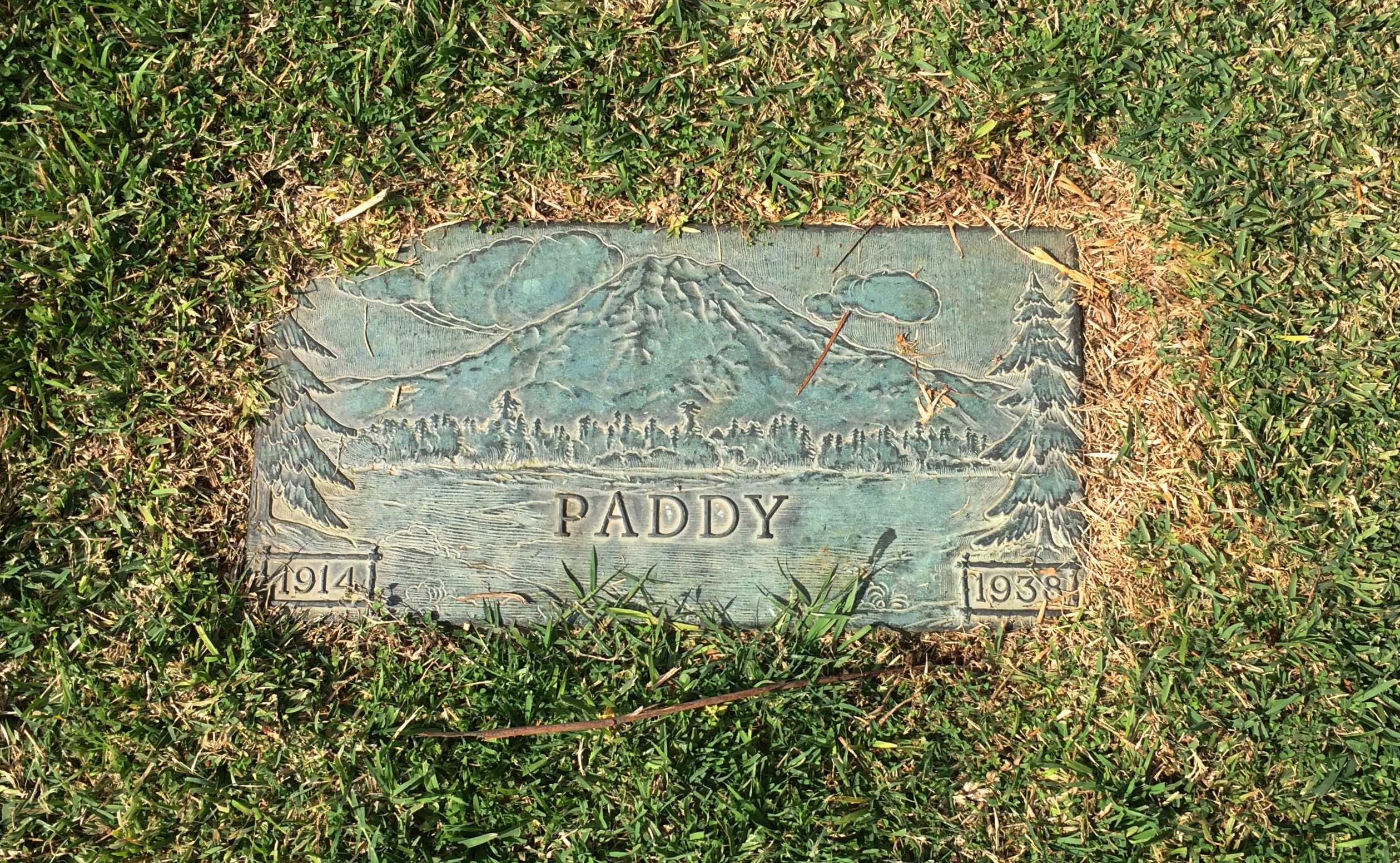

Hollywood Forever also sports a number of unconventional memorials. Something you might expect in California, except that I’ve seen them elsewhere.

Hollywood Forever also sports a number of unconventional memorials. Something you might expect in California, except that I’ve seen them elsewhere.

Or maybe not unconventional, but just a little unusual.

Or maybe not unconventional, but just a little unusual.

Plenty of regular folks, too. Most of the permanent population would be, I believe. John Taylor was laid to rest just as the movie business started getting off the ground in Hollywood.

The cemetery dates back to 1899 and has had three names: Hollywood Cemetery, Hollywood Memorial Park, and since 1998, Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Its history is as strange as Hollywood itself.

A long-time owner in the 20th century essentially used the place as a piggy bank, and let it go to pot by the 1990s. The current owner invested millions in the property’s renovation — or oversaw the investment, and I’ll say it again, did a splendid job — with the funds at least partly generated by a pre-need funeral company Ponzi scheme his father and brother went to prison for, though the owner himself wasn’t charged. Sounds like a subplot in the entertaining and California-esque Six Feet Under, except the con was perpetrated in Missouri.

The whole story is more than I care to unpack, but for further reading there’s “The Strange History of Hollywood Forever Cemetery,” an article about the Ponzi scheme, and this entertaining article in LA Weekly.

Not only has the current owner made the cemetery look good, he’s raised public awareness of it through various events, such as outdoor movie screenings and other events not usually associated with graveyards. Also — and perhaps most astute of all, from a business perspective — he seems to have opened up space to be interred, especially in mausoleums near famous people (example to follow).

That brings me to the fact that I’ve buried the lead (har, har). All the features I’ve mentioned above are nice, but not really why I spent a couple of hours at Hollywood Forever on a pleasantly warm Sunday morning.

I’d come to find the graves of movie stars. Normally, celebrity earns a shrug from me. But I was in Hollywood. Movie stars are part of its sense of place. It’s a movie industry town, after all. Besides, a highly detailed map of the cemetery is available at the front office for a reasonable $5, and it guides you to the graves of about 200 notables.

“We sell more of these maps than we do flowers,” the lady behind the counter told me.

So I was on a treasure hunt to find some stars that I’d heard of, especially from the Hollywood of before I was born, more or less. It was fun.

Grand names are part of the deal at Hollywood Forever. Parts of the cemetery include the Garden of Eternal Love, Chandler Gardens, Garden of Memory, and a Jewish section featuring the Plains of Abraham, Garden of Jerusalem and Garden of Moses. This is the the entrance is the Abbey of Psalms Mausoleum.

I entered in search of the Crying Indian, Iron Eyes Cody. I found him in a modest niche. His wife, who died about 20 years before he did, rests there as well. She’s called “Mrs. Iron Eyes Cody” on the plaque; you have to look her up to learn she had a name besides her Italian-American husband’s made-up Native American name. She was Bertha Parker Pallan and, unlike him, was actually an Indian.

I entered in search of the Crying Indian, Iron Eyes Cody. I found him in a modest niche. His wife, who died about 20 years before he did, rests there as well. She’s called “Mrs. Iron Eyes Cody” on the plaque; you have to look her up to learn she had a name besides her Italian-American husband’s made-up Native American name. She was Bertha Parker Pallan and, unlike him, was actually an Indian.

Iron Eyes is small potatoes compared to the real star of the Abbey of Psalms: Judy Garland. She has her own chapel-like room, re-interred there only in 2017. That must have been quite a coup for Hollywood Forever.

Want to have your ashes near Judy? It can be arranged. A lot of new-looking, glass-door niches are in the chapel walls, most still empty, though I did note that John Cassese, the “Dance Doctor,” recently occupied an eye-level niche across from Judy. His niche includes an urn, but also a bobblehead-like figure of him, a printed obituary, an award he won in 2013, a small disco ball, some seashells and other objects.

From there I headed to the open air, looking for Mel Blanc.

I left a penny. Here was a man who had entertained me and millions of others.

I left a penny. Here was a man who had entertained me and millions of others.

Most of the graves I wanted to see were in the Garden of Legends, an open area, and the Cathedral Mausoleum, so I soon headed that way. Douglas Fairbanks and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. have their own lawn and reflecting pool, with a major memorial next to the Cathedral Mausoleum.

The cemetery shop only had a few postcards for sale, but they included ones featuring Douglas Fairbanks, probably dressed for The Black Pirate and looking very much like the actor who invented swash and buckle. I sent one of them to a friend of mine and wrote, “You or I might be cool, but we’ll never be Douglas Fairbanks cool.”

The cemetery shop only had a few postcards for sale, but they included ones featuring Douglas Fairbanks, probably dressed for The Black Pirate and looking very much like the actor who invented swash and buckle. I sent one of them to a friend of mine and wrote, “You or I might be cool, but we’ll never be Douglas Fairbanks cool.”

Heading into the Garden of Legends, I soon happened across Johnny Ramone. I didn’t even know he was dead.

Nearby is a cenotaph for Hattie McDaniel, who was denied burial here in 1952 because of segregation. Her memorial was erected in 1999.

Nearby is a cenotaph for Hattie McDaniel, who was denied burial here in 1952 because of segregation. Her memorial was erected in 1999.

Next I spent a while looking for Fay Wray, and found her, and then Erich Wolfgang Korngold. The composer is buried under a tree.

I sent the picture to my old friend Kevin, a movie music enthusiast. But for Kevin I might not know about Korngold, or have ever listened to such treasures as the music from The Adventures of Robin Hood or The Sea Hawk.

I sent the picture to my old friend Kevin, a movie music enthusiast. But for Kevin I might not know about Korngold, or have ever listened to such treasures as the music from The Adventures of Robin Hood or The Sea Hawk.

Rounding the pond that forms the centerpiece of Garden of Legends, I came across Cecil B. DeMille.

One I hadn’t been looking for: Virginia Rappe.

One I hadn’t been looking for: Virginia Rappe.

I puzzled for a moment. Who was that? Then I remembered.

I puzzled for a moment. Who was that? Then I remembered.

Tyrone Power is hard to miss.

Next to him is Marion Davies’ mausoleum, which you might miss if you don’t know that her actual name was Douras, which is above the entrance. She paid for the building herself, I’ve read.

Next to him is Marion Davies’ mausoleum, which you might miss if you don’t know that her actual name was Douras, which is above the entrance. She paid for the building herself, I’ve read.

At the Cathedral Mausoleum, an even larger complex than the Abbey of Psalms Mausoleum, I found Peter Lorre in a niche. I was looking for him. I also found Mickey Rooney. I wasn’t looking for him, but he does illustrate that stars are once again considering the cemetery, now that the period of neglect is over.

At the Cathedral Mausoleum, an even larger complex than the Abbey of Psalms Mausoleum, I found Peter Lorre in a niche. I was looking for him. I also found Mickey Rooney. I wasn’t looking for him, but he does illustrate that stars are once again considering the cemetery, now that the period of neglect is over.

Rooney’s inscription says: “One of the greatest entertainers the world has ever known. Hollywood will always be his home.”

Well, de mortuis nihil nisi bonum, Mickey, though I want to mock that inscription. Then I began noticing some other recent arrivals from the movie business, most of whom I’d never heard of. Some of the memorials were like ads in Variety, touting their careers.

Last stop: Valentino. I couldn’t very well miss him.

I’d read that lipstick is often there, and so it was. He’s got amazing staying power for a silent film star.

I’d read that lipstick is often there, and so it was. He’s got amazing staying power for a silent film star.

Curious, I took note of the grave next to Valentino: June Mathis Balboni (d. 1927). Just an accident that this person is next to the Great Lover?

No. She knew him. In fact, she discovered Valentino and wrote some of his movies, most notably The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Remarkable the tales that cemeteries tell.

It’s a small slice of a cemetery, about 300 burials, many of which are recent. Those names tend to be more varied: Abraham, Burkinshaw, Dunbar, Ek, Hernandez, Pastori, Smakal and Tumminaro.

It’s a small slice of a cemetery, about 300 burials, many of which are recent. Those names tend to be more varied: Abraham, Burkinshaw, Dunbar, Ek, Hernandez, Pastori, Smakal and Tumminaro. For an infant, born and died in 2004.

For an infant, born and died in 2004.

I looked up Jake. A bright lad, just a little younger than my oldest child, who died suddenly of an undetected heart condition.

I looked up Jake. A bright lad, just a little younger than my oldest child, who died suddenly of an undetected heart condition.