Our stroll through a small slice of the Hyde Park neighborhood on Sunday took us westward on E. 57th St. for a few blocks, roughly between S. Kenwood Ave. and S. University Ave. As you head west, small businesses and flats give way to university property.

Mostly. This is the 57th St. side of the First Unitarian Church of Chicago.

According to the AIA Guide to Chicago, the church, which was completed in 1931, is a “textbook example of English Perpendicular Gothic design [that] fits in easily with the limestone facades and Gothic ornament of many Hyde Park residences and university buildings.”

According to the AIA Guide to Chicago, the church, which was completed in 1931, is a “textbook example of English Perpendicular Gothic design [that] fits in easily with the limestone facades and Gothic ornament of many Hyde Park residences and university buildings.”

Denison B. Hull did the design. “The son of a five-term, Republican U.S. representative, Morton Hull, he grew up in the Hyde Park area that his father represented in the 1920s,” the Chicago Tribune said in his 1988 obit.

“After serving as an officer in World War I, Mr. Hull was graduated from Harvard University. In 1922, he won first prize in an architectural design contest conducted by the university.

Among his noted architectural work, besides the First Unitarian Church, were the restoration of Old Church and the expansion of the historical museum, both in Bennington, Vt…

Mr. Hull was noted also as a scholar of ancient Greek and Greece.”

They don’t make ’em like that anymore.

I’ve never been able to see the inside of First Unitarian. Services are at 10 a.m. Sunday, and if I ever happen to be in Hyde Park then, I will attend one. Not just to see the interior, but also to see whatever it is Unitarians do during their services.

At 1219 E. 57th St. is the Neubauer Family Collegium for Culture and Society. More simply, the Neubauer Collegium.

According to a sign in front, exhibits can be seen inside, but not, as it happens, on Sunday. I wondered just what the organization was, and why I’d never heard of it. To answer the second question first: it was founded only in 2012, and makes its home in the former Meadville-Lombard Seminary Building.

As for what it does, the Neubauer — as best as I can describe it — is a humanities think tank.

UChicago News says: “The Neubauer Collegium will unite scholars in the common pursuit of ideas of grand scale and broad scope, making the University of Chicago a global destination for top scholars engaged in humanistic research while also pioneering efforts to share that research with the public.”

Here’s the view of the Reynolds Club bell tower from near 57th St.

As probably no one calls it: the John J. Mitchell Tower of the Joseph Reynolds Student Clubhouse. These days, the clubhouse, completed in 1903, is a student union. Joseph “Diamond Jo” Reynolds was a Gilded Age steamboat and railroad magnate whose bequest paid for the building; I believe John J. Mitchell was a Chicago banker who seems to have died in a road-rage incident.

As probably no one calls it: the John J. Mitchell Tower of the Joseph Reynolds Student Clubhouse. These days, the clubhouse, completed in 1903, is a student union. Joseph “Diamond Jo” Reynolds was a Gilded Age steamboat and railroad magnate whose bequest paid for the building; I believe John J. Mitchell was a Chicago banker who seems to have died in a road-rage incident.

As Time reported in 1927:

Near Chicago last week death came to banker John J. Mitchell, and to Mrs. Mitchell. They were driving in an open motor car from their country home at Lake Geneva, Ill., to Chicago for the funeral of their elder daughter’s father-in-law, when their machine met a roadside brawl. Two motor cars, going in opposite directions had tried to pass a hay wagon at the same time. Both cars went into a ditch; the drivers jumped clear and fell to words and fisticuffs. The haywagon stopped as did several machines. Their drivers wanted to see…

To read more, I’d have to subscribe, but I’d rather leave the story at that.

Here’s the view of the tower from inside the quad formed by the Reynolds Club and some other buildings.

Designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, the building was “derived from St. John’s College at Oxford, and its domestic feeling is enhanced by a stair hall that could have come straight out of an English manor house.”

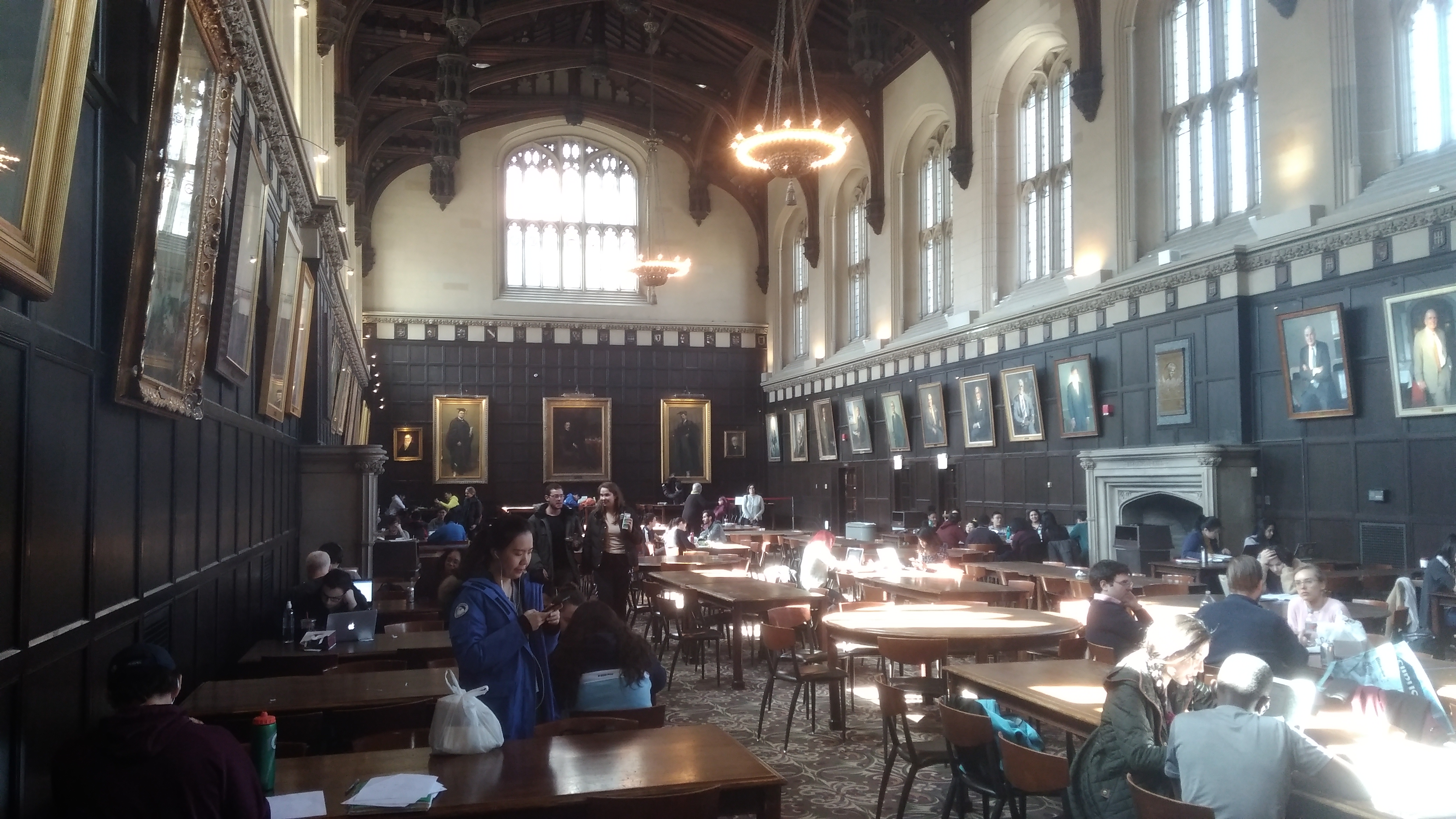

Also inside — behind the row of windows to the left of the tower, above — is the Charles L. Hutchinson Common, which SRC did as well. Hutchinson, better known as founder of the Art Institute of Chicago, ponied up for building the hall.

It’s also like stepping into Oxford. According to Wiki, anyway, “The Harry Potter film series has used the original hall at Christ Church in each of its films, imparting a tourist interest in its American replicate.[citation needed].”

It’s also like stepping into Oxford. According to Wiki, anyway, “The Harry Potter film series has used the original hall at Christ Church in each of its films, imparting a tourist interest in its American replicate.[citation needed].”