In January 1990, when I knew I was leaving Chicago and not sure I’d ever move back, I spent some time visiting local places I hadn’t gotten around to. That included a few smaller museums, such as the DuSable Museum of African-American History, the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, and what was then known as the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum. Now it’s the National Museum of Mexican Art, but the museum is still located in Harrison Park in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago. I made it back there on Saturday for first time in 25 years.

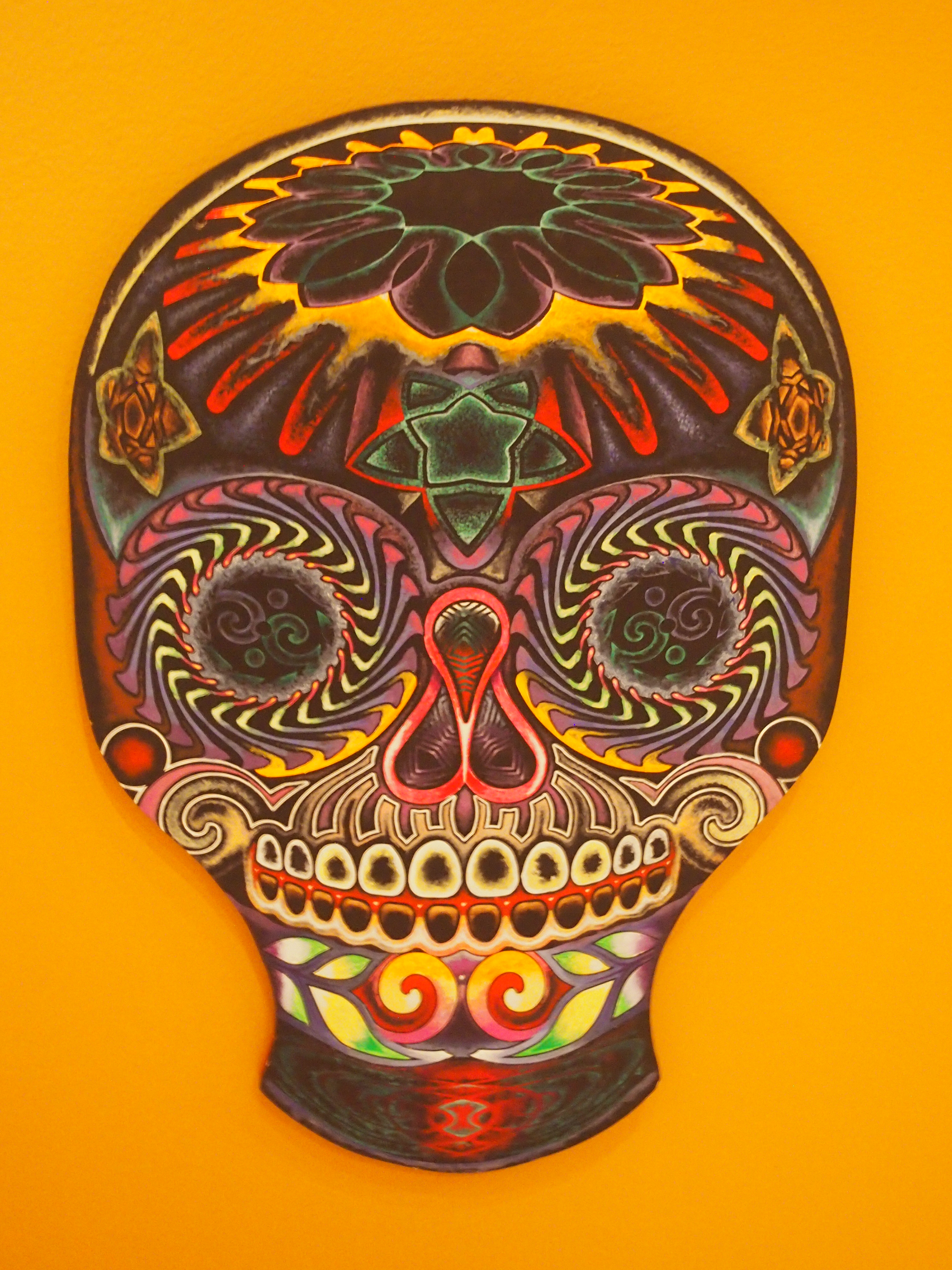

Mainly I wanted to see the museum’s notable Día de los Muertos exhibit, which it mounts every October through December. Who can resist colorful skulls, in two and three dimensions?

But there was much more. “Come celebrate the Day of the Dead with the works of over 90 artists of Mexican descent from both sides of the border,” the museum web site notes. Among other works, “thirteen ofrendas and installations were created to remember distinguished artists and members of the community alike. Folk art, paintings, and sculptures comprise the largest annual exhibition of Day of the Dead in the U.S.”

But there was much more. “Come celebrate the Day of the Dead with the works of over 90 artists of Mexican descent from both sides of the border,” the museum web site notes. Among other works, “thirteen ofrendas and installations were created to remember distinguished artists and members of the community alike. Folk art, paintings, and sculptures comprise the largest annual exhibition of Day of the Dead in the U.S.”

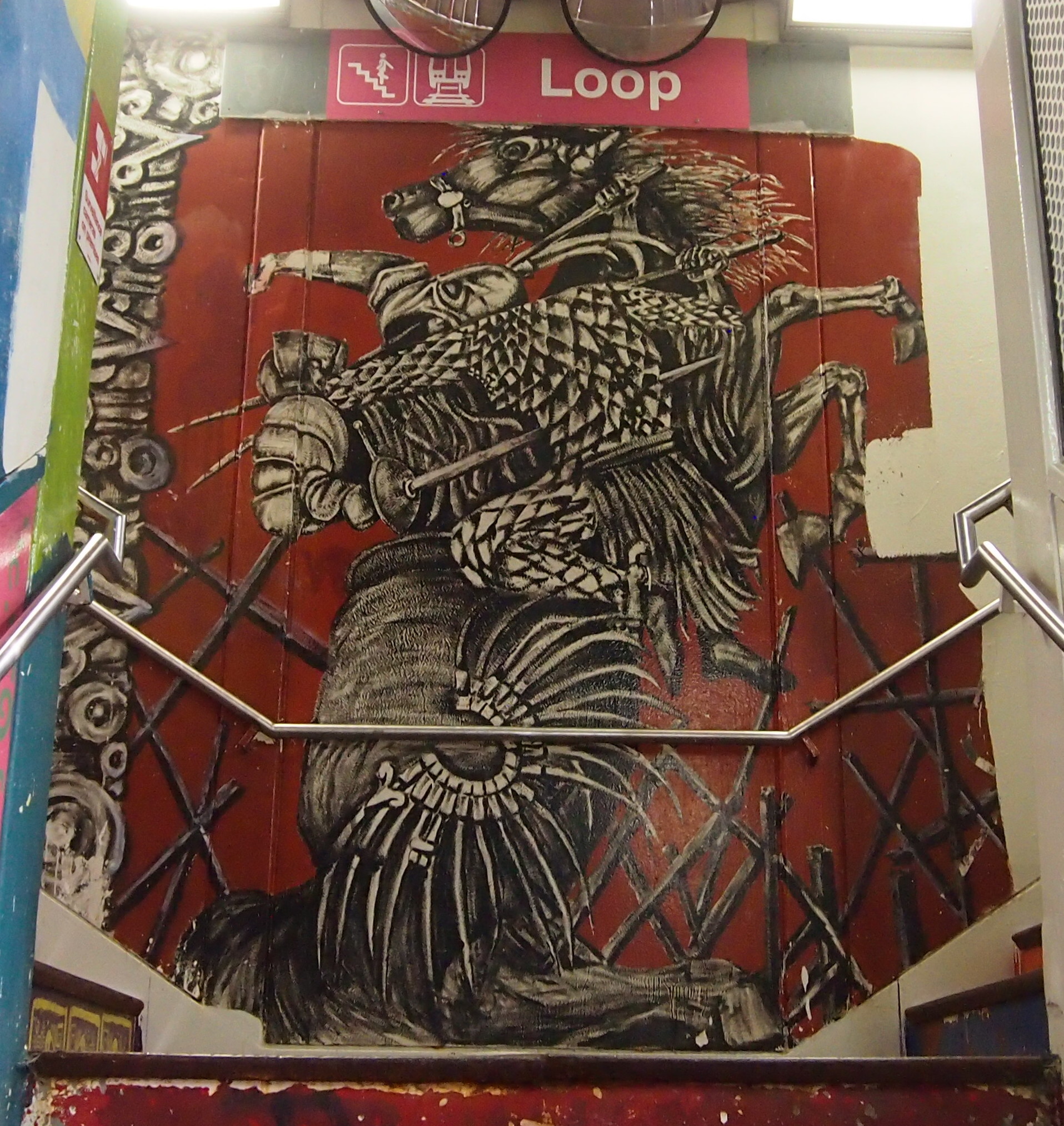

The ofrenda (“offering”) consists of objects arrayed on a ritual altar for the Day of the Dead, to honor someone who has died. The one that really caught my attention was for El Santo of Lucha Libre fame.

The title of the ofrenda in full: “Santo in the World of the Dead: Altar to the Silver Masked Wrestler/Santo en el mundo de los muertos: ofrenda al enmascarado de plata,” by Juan Javier and Gabrielle Pescador of Michigan.

The title of the ofrenda in full: “Santo in the World of the Dead: Altar to the Silver Masked Wrestler/Santo en el mundo de los muertos: ofrenda al enmascarado de plata,” by Juan Javier and Gabrielle Pescador of Michigan.

I had only the vaguest notion of El Santo, so I read more about him: Rodolfo Guzmán Huerta (1917-1984), one of the biggest stars of Lucha Libre. It’s too bad that some of his many movies, dubbed clumsily in English, didn’t show up on Saturday afternoon TV when I was young. Such as Santo vs. las Mujeres Vampiro, a poster for which is part of the ofrenda. After all, we did get the likes of The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy on English-language TV in ’70s San Antonio.

Not to worry, in our time the original version of Santo vs. las Mujeres Vampiro is posted in its entirety on YouTube. If you watch it, and maybe a few other Santo clips, you might start getting YouTube commercials in Spanish, which I find easier to ignore.

(Something that made me smile from the Wiki entry on The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy: “The movie shows a notable lack of awareness of Mesoamerican civilizations…” There’s a shocker.)

Another large ofrenda was for a woman in a rather different walk of life, though a public persona all the same: Irene C. Hernandez (1916-1997), who was on the Cook County Board of Commissioners from 1974 to ’94.

The work was created by a number of artists, including students at Irene C. Hernandez Middle School in Chicago. A lot of skeletons have their parts to play.

The work was created by a number of artists, including students at Irene C. Hernandez Middle School in Chicago. A lot of skeletons have their parts to play.

Other ofrendas and installations honored the likes of Anthony Quinn, Selena, Brooklyn artist Ray Abeyta, and notable Chicagoans like Soledad “Shirley” Velásquez. Considering that the theme is death, they’re remarkably life-affirming.

Other ofrendas and installations honored the likes of Anthony Quinn, Selena, Brooklyn artist Ray Abeyta, and notable Chicagoans like Soledad “Shirley” Velásquez. Considering that the theme is death, they’re remarkably life-affirming.

I’ve read that giant grasshoppers crawled on the building in The Beginning of the End (1957). “You can’t drop an atom bomb on Chicago,” protests a young Peter Graves. That does seem like burning down the house to get rid of the termites, but never mind.

I’ve read that giant grasshoppers crawled on the building in The Beginning of the End (1957). “You can’t drop an atom bomb on Chicago,” protests a young Peter Graves. That does seem like burning down the house to get rid of the termites, but never mind. They too have been in movies, notably The Hunter (1980), which was Steve McQueen’s last picture. I haven’t seen the whole thing, but in the age of YouTube, it’s easy to see just the part in which a car plunges from the towers — which have parking decks on their lower levels — into the Chicago River. The scene was so good that a similar one was created for an insurance commercial, though I have to add that if you’re running from the cops, I doubt that any policy’s going to cover the damage.

They too have been in movies, notably The Hunter (1980), which was Steve McQueen’s last picture. I haven’t seen the whole thing, but in the age of YouTube, it’s easy to see just the part in which a car plunges from the towers — which have parking decks on their lower levels — into the Chicago River. The scene was so good that a similar one was created for an insurance commercial, though I have to add that if you’re running from the cops, I doubt that any policy’s going to cover the damage.