It was a first for me: a church with a lime-green interior wall, all the way around, and a large cross created by colorful lights, as a fixture on the ceiling. To find this church, you take the Green Line south to the 43rd St. station, and then walk west on 43rd. At Wabash Ave., turn left – to the south — and there you are, at 4315 S. Wabash: The First Church of Deliverance.

I’ve seen it described as a rare example of Art Moderne in a house of worship. I’ll go along with that. One Walter T. Bailey designed the structure toward the end of this career, which involved a practice in Chicago and Memphis, doing (among other designs) a number of Knights of Pythias buildings, including this one I’d never heard of near Nashville.

Lee Bailey, writing for WBEZ, says: “The church was built in 1939 and designed by Walter T. Bailey, the first African American to hold an architecture license in Illinois. Those terra cotta-clad twin towers were added in 1946, designed by Kocher Buss & DeKlerk. The building’s modernity wasn’t by chance. In the 1930s and 1940s, First Church was an exceedingly modern congregation.

“The Rev. Clarence H. Cobbs was only 21 when he founded the predominantly black First Church congregation in 1929. The church began its radio broadcast in 1934, giving Cobbs and his 200-member choir a national reach and influence. The congregation’s choir revolutionized the sound of gospel music in 1939 when its organist and composer Kenneth Morris convinced Cobbs to install the newly created Hammond electric organ at the church. The church’s gospel festivals in old Comiskey Park in the 1940s drew thousands.

“In 1953, the congregation became the first black church in the U.S. (quite possibly the world) to broadcast its services on television. WLS-TV carried those services live — a significant development, in retrospect — for 12 straight weeks. Songs that later became gospel standards made their debut at the church under Hobbs, including the staple ‘How I Got Over.’ ”

The interior is auditorium-style, and green is the first thing that strikes you. Then the details, especially the luminous ceiling cross.

Up closer to the front.

Up closer to the front.

Nearby, at 4359 S. Michigan Ave., is the Centennial Missionary Baptist Church. Once upon a time, it was the Eighth Church of Christ, Scientist. Actually, not that long ago.

Nearby, at 4359 S. Michigan Ave., is the Centennial Missionary Baptist Church. Once upon a time, it was the Eighth Church of Christ, Scientist. Actually, not that long ago.

It too is an auditorium church, but more semicircular. In that way it reminded me of the Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist, which is downtown.

It too is an auditorium church, but more semicircular. In that way it reminded me of the Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist, which is downtown.

A nice woman named Doris gave us a tour, including not only the main part of the church, but some back rooms. Open House Chicago notes that “Designed in 1911 by architect Leon E. Stanhope, the Centennial Missionary Baptist Church was originally home to the Eighth Church of Christ, Scientist. Designed in the neoclassical style, with a striking red domed roof, it was one of the longest-running African American Christian Science congregations.

“The building only recently became home to Centennial Missionary Baptist Church – which itself boasts a distinguished history. Their first house of worship was a building owned by Lorraine Hansberry, and numerous gospel music greats performed over the years.”

The third church we visited in Bronzeville, Mount Pisgah Missionary Baptist Church, 4600-4622 S. King Dr., began as the Chicago Sinai Temple in the early 1910s, designed by the prolific Alfred Alschuler. I didn’t take any exteriors, but Design Slinger has some good images.

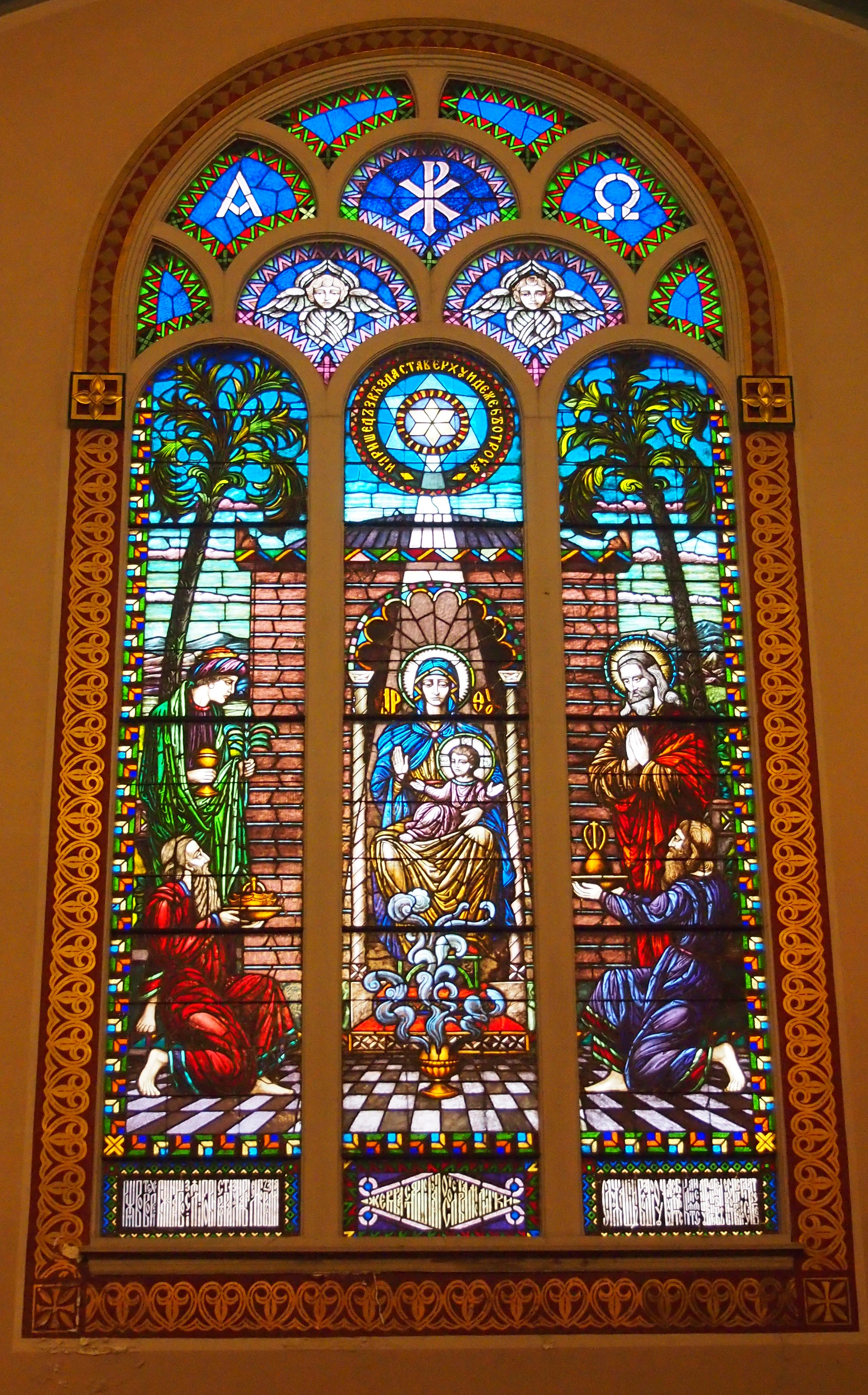

The exterior is stately, while the interior is gorgeous.

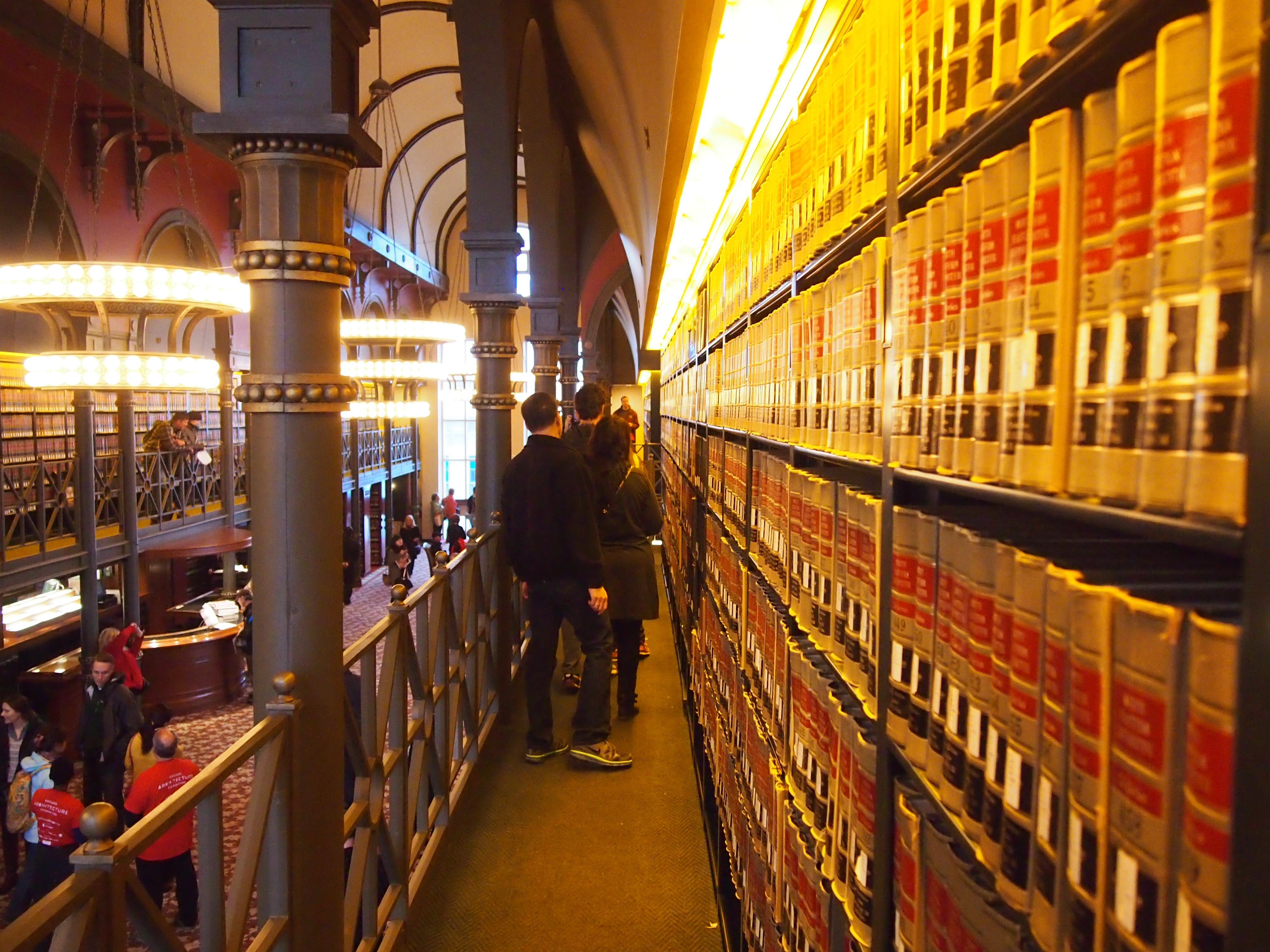

Design Slinger says: “In 1910 architect Alfred Alschuler drew up plans for a Chicago Sinai building complex that would include an auditorium for worship and a large community center which would house offices, classrooms, meeting spaces, a gym and a pool…. as members moved further south, a large corner lot was purchased at 46th and Grand Boulevard to serve as a new home base.

Design Slinger says: “In 1910 architect Alfred Alschuler drew up plans for a Chicago Sinai building complex that would include an auditorium for worship and a large community center which would house offices, classrooms, meeting spaces, a gym and a pool…. as members moved further south, a large corner lot was purchased at 46th and Grand Boulevard to serve as a new home base.

“Since the congregation was part of the Reform tradition, Alschuler followed a design scheme that was popular at the time with other congregations in not proclaiming that the building was a house of worship, by choosing a historical classic architectural style. The restrained sophistication of Greco/Roman refinement would convey to the passerby that this was a substantial edifice, it could be a bank or a library, but not wear its religious affiliation on its sleeve.”

By the 1940s, the Jewish population in the area couldn’t sustain a synagogue, and the structures became part of the high school run by Franciscans. In 1961, Mt. Pisgah Missionary Baptist congregation acquired the property.