I can’t say whether Billy Goat Tavern & Grill looks exactly the same as it did in the ’80s, but it sure felt the same on Monday night. The walls of photos, neon, beer taps, rows of bottles, knickknacks and basic restaurant tables and chairs, and plenty of worn red bar stools. The vibe is Chicago tavern clutter, comfortable as an old shirt.

Now that I think about it, I had the most Greek experience I’ve ever had at the Billy Goat, having never yet made it to Greece. Shortly before the 1988 presidential election, the Dukakis campaign staged a campaign parade on Michigan Avenue, and after work I went to watch, on a spontaneous quasi-date with a fetching Greek-American woman I knew. Was it a torchlight parade? In my memory, there were torches, but probably no: that seems like a 19th-century thing.

We were within feet of the candidate as he walked by, his expression a little stiff and discouraged. Later we repaired to the Billy Goat, which was wall-to-wall packed, including many Greek Americans – wearing the colors of the Greek flag, some of them — with everybody feasting on cheeseburgers and beer, the place alive with talk, and the clank of spatulas on the grill, and the hissing burgers and onion air, and the clouds of cigarette smoke still common in bars and restaurants.

I’m pretty sure the workers called out Cheezborger! Cheezborger! in those days, which might be an example of life imitating art, or more likely, life and art reinforcing either other.

Rumor was that Dukakis himself would make an appearance, and well he should have, but he never did. He should have shown up in his tank helmet, shaking hands and mugging for cameras. Rather than be embarrassed by it, he should have leaned into it, but no.

Back here in the 21st century, there are reminders of goats at Billy Goat. How could it be otherwise?

You can see a wall of bylines at Billy Goat. Once upon a time, both major Chicago newspaper buildings were within easy walking distance, even in winter, so newspapermen hung out there.

Best known was Royko, who worked the place into his column from time to time. From there, the place went on to wider notice, sort of.

I expect the number of journalists is fairly low these days, outnumbered by other kinds of downtown residents and workers, plus tourists. On Monday night at least, no one called out when you ordered your cheeseburgers; they just went to work at it.

Except for the vegan in our group – she was a good sport about it — we had cheeseburgers and chips and beer. What else? In theory, a few other things are on the menu, but we didn’t test it. No fries, either.

We also sipped from a single glass of Malört. It’s a Chicago thing to do.

Around the corner from the entrance of the Billy Goat, directly facing Lower Michigan Ave. and just north of the Chicago River., is a mural and a tavern sign.

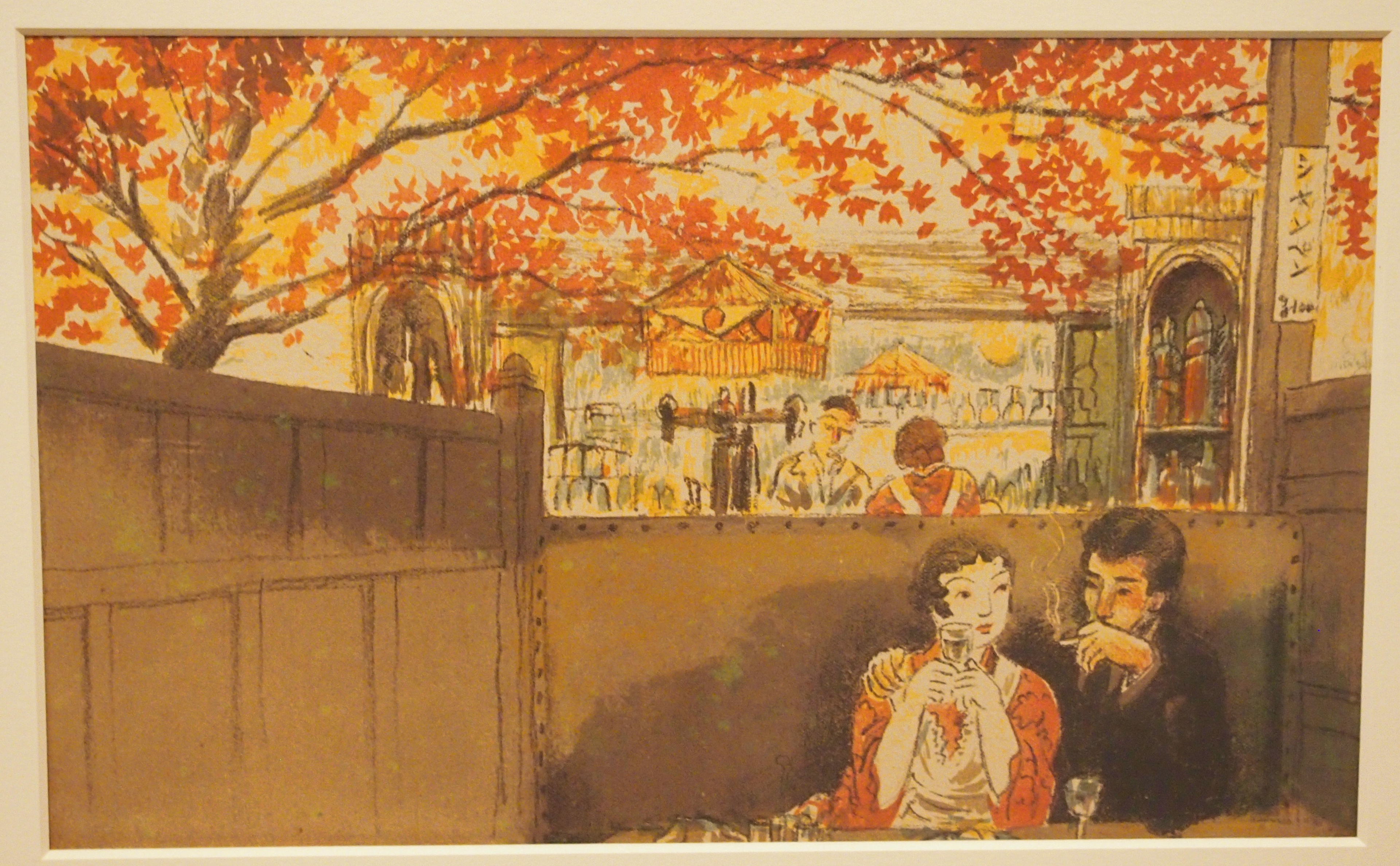

The mural is a work by Andy Bellomo, “a self-taught artist who began her creative interest as a young teen studying the color, light, shapes, and lines of traditional stained glass in churches,” according to the the Magnificent Mile Association, as part of a number of murals known as Undercurrent (at least to the Mag Mile Assn.).

It’s been there about a year, which would account for me never noticing it before. Haven’t been down to Lower Michigan Ave. in a some years, but I can assure the world that it’s still the hard urban space it’s always been.

There’s more of the Undercurrent mural on the other side of the tavern’s entrance, not captured in the below image.

But I did capture, without realizing it, part of a different mural, one that’s been there for decades, by an artist mostly lost to time in Chicago, even though his heyday was only about 50 years ago. It’s on the extreme right edge of the image: a rainbow goat.

“Many people ask about the rainbow goats painted on the walls outside of The Goat,” notes the tavern web site. “They were painted in 1970 by Sachio Yamashita, known as Sachi… Billy [Sianis, original owner of the tavern] made a deal with Sachi. Every day after Sachi and his helpers finish their work, beer and borgers are free! Unfortunately Billy Goat Sianis passed away on October 22, 1970 just days before the paintings were complete.”

I might have noticed the goats before, but didn’t give them much thought. I didn’t notice them this time, or I’d have taken a full image, since how many rainbow goats could there be in the world? On walls, that is.