Early last year, I ordered a number of 4″ x 6″ tabletop flags from an online vendor that doesn’t happen to be Amazon. I have pocket change and postcards and tourist spoons and all kinds of bric-a-brac from the places I’ve been, so why not flags? One for each nation I’ve visited.

So I ordered a Portuguese flag last week, to add to the collection. While Macao was still administrated by Portugal when I visited in 1990, it was too much of a stretch to say I’d been to Portugal, until last month.

Something I never noticed on the flag – behind the shield of Portugal, which has a lore of its own – is an armillary sphere, a model of objects in the sky. A navigators’ tool, among other things, which fits Portuguese history nicely. A cool design element.

We saw other representations of the globe — terrestrial or celestial — at Pena Palace in Sintra.

This one at Jerónimos Monastery.

For sale at the Cod Museum, canned fish. At fancy prices.

For sale at a Portuguese grocery store, canned fish. At everyday prices.

In case you didn’t buy enough canned fish in the city, at the airport there’s a branch of Mundo Fantástico Da Sardinha Portuguesa, a sardine store on the Praça do Rossio.

For once, the Google Maps description is accurate: “Souvenir shop showcasing fancy tins of Portuguese sardines in a wacky, circuslike atmosphere.” You can even sit on a sardine throne.

The “Beer Museum” off Praça do Comércio seemed more like a restaurant and bar, but anyway you have to have a beer at a place like that, and I did. A Portuguese brew whose name I was too much on vacation to remember.

I wasn’t awed by the beer, which was good enough, but I was awed by this display. That’s one artful wall of beer.

We didn’t make it to the castle overlooking Lisbon (Castelo de São Jorge), so I can’t comment on the view from there. I will say that the roof of our hotel offered a pretty good one.

Looking up at the city is another kind of vista. There’s a ferry port (and subway station) on the Tagus near Praça do Comércio. Step outside there, and some of the city is visible. The stone tower is part of Lisbon Cathedral.

We emerged from the subway one morning and spotted this.

Monumento aos Mortos da Grande Guerra. I had to check, and found out that about 12,000 Portuguese soldiers died in WWI, including in France but also fighting the Germans in Africa. The memorial is on Av. Da Liberdade.

Europe, in my experience, is pretty good at putting together leafy boulevards.

That’s a tall order for a sandwich shop. We didn’t investigate the claim, either the number of steps, nor the state of mind.

At Basílica de Nossa Senhora dos Mártires, we encountered this fellow.

Rather Roman looking, and I mean the ancient Roman army, not “prays like a Roman with her eyes on fire.” At first I thought he might be Cornelius the Centurion, but the key clue is HODIE (“today”) written on the cross, meaning he’s Expeditus. I don’t ever remember seeing him depicted in a church. The patron of urgent causes, among other things.

We saw a flamenco show in Barcelona last year, but no fado in Lisbon. We did see a fado truck, however.

We ate at the Time Out Market Lisboa twice.

There was a reason it was crowded. Everything was a little expensive, but really good. Such as this place, whose grub was like Shake Shack.

The last meal of the trip wasn’t at Time Out Lisboa, but a Vietnamese restaurant with room enough for about 20 people. It too was full.

Spotted at one of the subway stations we passed through more than once. Alice in Wonderland‘s fans are international in scope.

On the whole, the Lisbon subways are efficient and inexpensive, and the lines go a lot of places. Even so, elevator maintenance did seem to be an issue. There were times when our tired feet would have appreciated an elevator, but no go.

Scenes from Parc Eduardo VII, which includes green space and gardens but also elegant buildings.

There was an event there that day, at least according to those blue signs, that had something to do with the Portuguese Space Agency. I didn’t know there was such a thing. I’d have assumed Portugal would participate in the ESA, and leave it at that. But no, the Agência Espacial Portuguesa was founded in 2019, and is looking to create a space port in the Azores.

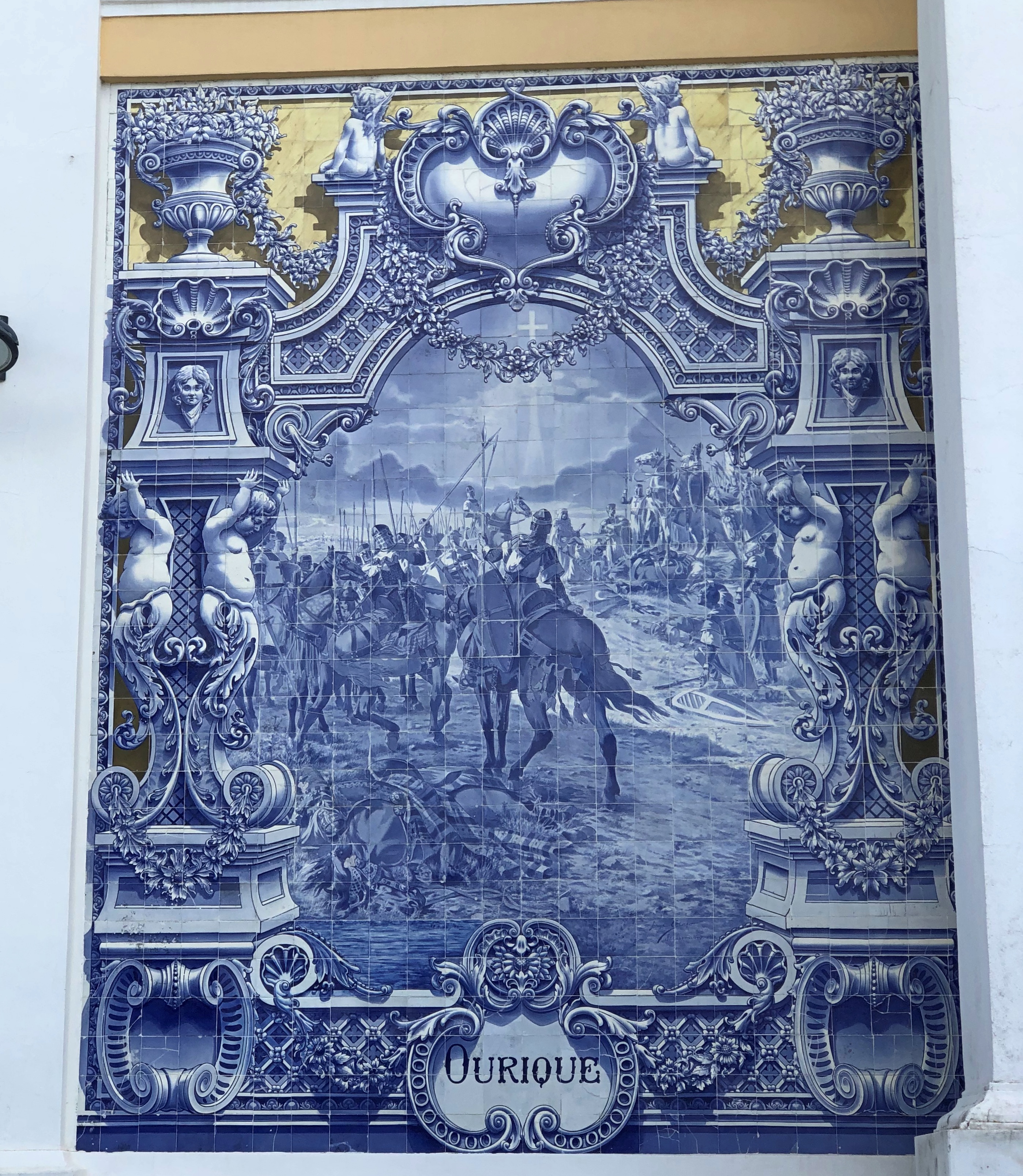

We didn’t investigate the event any further, but we did look at the tiles on the building. Nice.

Among the kings of Portugal, there was no Edward VII – only one Edward, who reigned from 1433 to 1438 – so when I saw it on the map, I figured it was for the British monarch of that regnal name. Yes, according to Wiki: “The park is named for King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, who visited Portugal in 1903 to strengthen relations between the two countries and reaffirm the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance.”

Lisbon manhole covers. Maybe not as artful as some of the other street details on Lisbon, but not bad.

I saw S.L.A.T. a fair amount. Later, I looked it up: Sinalização Luminosa Automática de Trânsito – Automatic Traffic Light Signaling.