Early in June, when we were visiting Arcola, Illinois, I noticed that the town sported more murals than it did during our 2007 visit. In fact, I didn’t remember any from that time. That’s because in 2012, Walldogs came to town and painted the murals.

I found that out by looking at Arcola’s web site, which mentioned the Walldogs, and then I looked them up. “The Walldogs are a group of highly skilled sign painters and mural artists from all over the globe…” the group’s web site says.

“Once a year, hundreds of Walldogs gather in one lucky town or city to paint multiple murals and old-fashioned wall advertisements. This meet – or festival – is usually held during the span of 4 or 5 days ending on a Sunday.”

More about the group was published recently by The Times, the area’s local paper.

While reading about the group, I noticed that the next Walldogs event was going to be in Streator, Illinois at the end of June. I knew right away that I wanted to go to Streator during the event, and that is what we did on Saturday. Since it was nearly 100 degrees F. during the early afternoon, we timed the visit so we didn’t get there until around 5:30 in the afternoon, when things had cooled off to around 90 or so, and it was easier to find shade.

Streator was glad to get the Walldogs, at least to judge by signs like this, placed in the window of a resale shop.

This is a mural to commemorate the event itself. It notes that this year is the 150th anniversary of Streator, the 200th anniversary of Illinois entering the Union, and 25 years of Walldogs events.

We’d been to Streator once before, but only for a short visit in 2005 that absolutely no one but me remembered.

We’d been to Streator once before, but only for a short visit in 2005 that absolutely no one but me remembered.

I wrote in a previous BTST: “Illinois 18 took us exclusively through flatlands, once the Illinois River valley was behind us, and on to Streator. Streator’s one of those towns that the Interstate system has completely bypassed. It didn’t seem any worse for it, though, with all the usual features of rural Illinois county seats [sic]: a small downtown, a district of fine-trim houses, a trailer park or two, parks, schools, a police station, firehouse, and library with a historic marker out front dedicated to the discoverer of Pluto.”

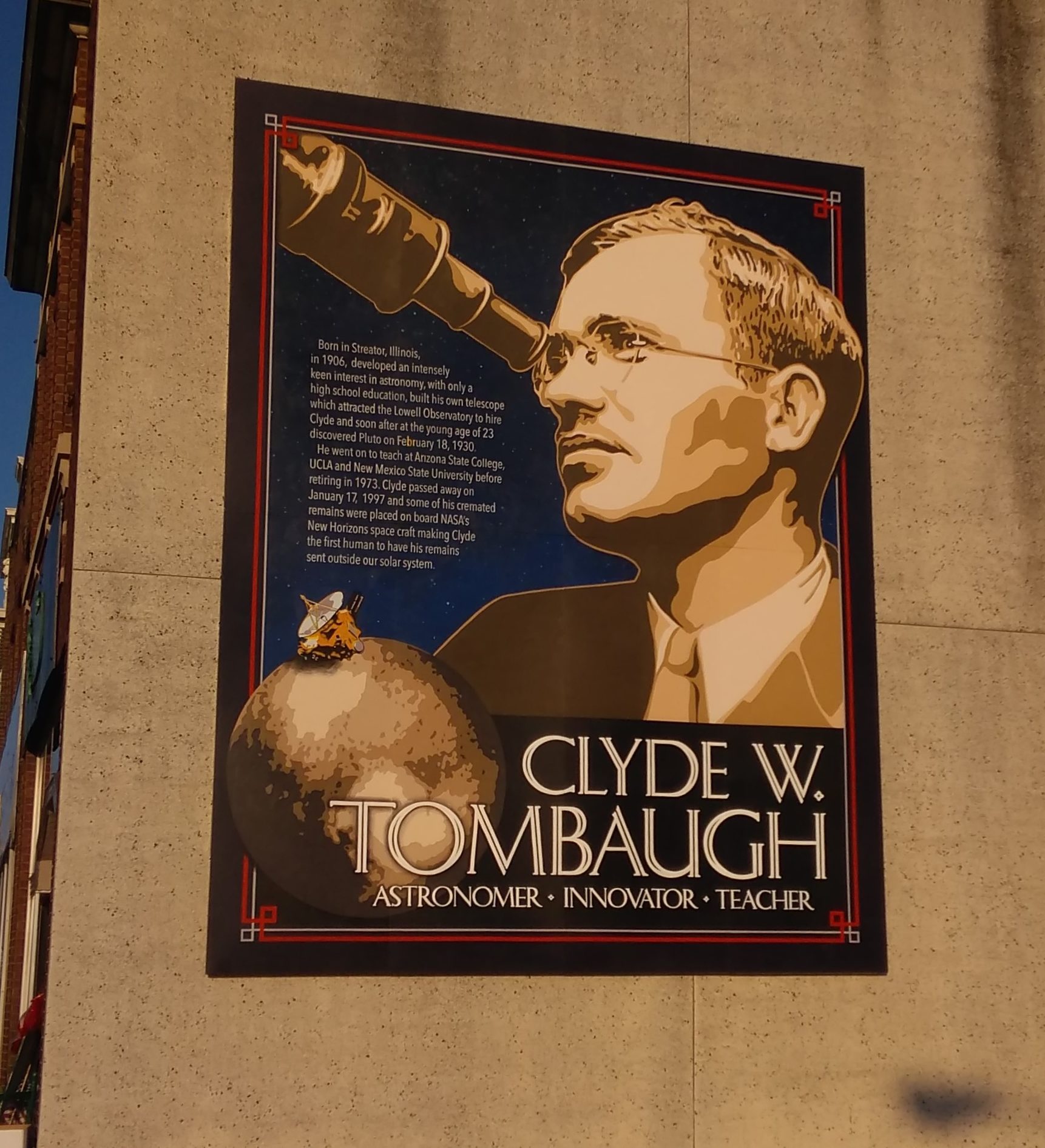

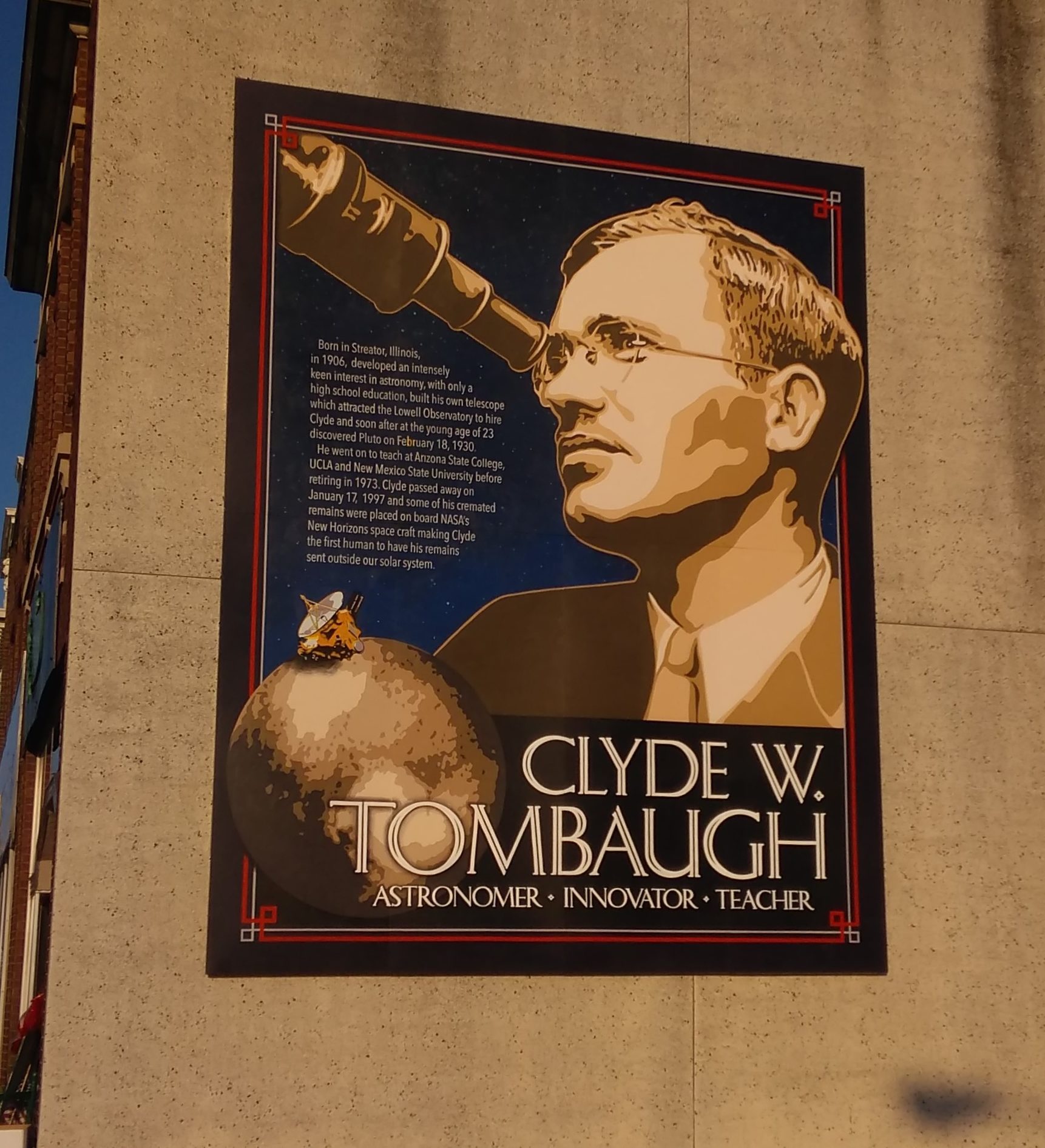

I stopped to read the sign, but didn’t even get out of the car. That was all I did in Streator. This time around, I knew that Clyde Tombaugh was going to get his own prominent Walldog mural in Streator, and sure enough, that was one of the first of the spanking-new murals we saw when we got to town.

So new, in fact, that the artists were still working on it.

Just before we left, however, the mural was visible for all to see.

Just before we left, however, the mural was visible for all to see.

It did me good to know that Streator hasn’t forgotten its favorite astronomical son, a lad from the Midwest who discovered a whole planet. I bet Pluto isn’t anything but a planet to the good people of Streator. Me either.

It did me good to know that Streator hasn’t forgotten its favorite astronomical son, a lad from the Midwest who discovered a whole planet. I bet Pluto isn’t anything but a planet to the good people of Streator. Me either.

Murals tend to be stylized, and so Tombaugh’s a stylized astronomer, looking through an eyepiece. Even in the 1920s and ’30s, I don’t think professional astronomers did that very much. After all, Tombaugh discovered Pluto by the tedious task of comparing photographic plates by eye, something that computers certainly do now.

Nearby were other walls with other brand-new murals, such as WWII Canteen.

They too are stylized, but supposedly there’s a story behind the couple on the wall. I didn’t get the details

Here’s Edward Plumb, a film composer who worked for Disney back when Walt himself was in charge, and who happened to be a grandson of the cofounder of Streator, Col. Ralph Plumb.

I noticed that Plumb’s mural is on the side of the boarded up Majestic Theater. No doubt once upon a time, you could hear his scores there as Disney movies played at the Majestic.

I noticed that Plumb’s mural is on the side of the boarded up Majestic Theater. No doubt once upon a time, you could hear his scores there as Disney movies played at the Majestic.

On this wall in the afternoon sun are Col. Plumb and Worthy Streator, town founders, along with the miners who came to dig coal in Streator’s early days, and a canary.

Some of the murals were being painted on aluminum panels fixed to temporary wooden scaffolding. The panels, I was told by a fellow who may or may not have been with the event, would be attached to walls later. Walls maybe not otherwise suitable for taking paint directly.

Some of the murals were being painted on aluminum panels fixed to temporary wooden scaffolding. The panels, I was told by a fellow who may or may not have been with the event, would be attached to walls later. Walls maybe not otherwise suitable for taking paint directly.

One honored native son was Clarence Mulford, creator of Hopalong Cassidy.

I’d say that Hopalong Cassidy is pretty much the definition of a forgotten figure from fiction. Even when I was growing up, he was little more than a vague Western character with an odd name.

I’d say that Hopalong Cassidy is pretty much the definition of a forgotten figure from fiction. Even when I was growing up, he was little more than a vague Western character with an odd name.

Another forgotten name, though not from fiction: Calbraith Rodgers.

Rodgers had his moment in the public eye in 1911, when he flew the Vin Fiz Flyer, a Wright Brothers machine, coast-to-coast over the course of about three months. Vin Fiz was a soft drink, in case anyone thinks product sponsorship is a new thing.

Rodgers had his moment in the public eye in 1911, when he flew the Vin Fiz Flyer, a Wright Brothers machine, coast-to-coast over the course of about three months. Vin Fiz was a soft drink, in case anyone thinks product sponsorship is a new thing.

According to Wiki: “The support team rode on a three-car train called the Vin Fiz Special, and included Charlie Taylor, the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop and aircraft mechanic, who built their first and later engines and knew every detail of Wright airplane construction; Rodgers’ wife Mabel; his mother; reporters; and employees of Armour and Vin Fiz.”

There’s a movie comedy in that story. Or there was, back in the 1960s, when the likes of The Great Race and Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines were made.

Rodgers might have reached further heights of aviation fame, but he died in a crash soon after his transcontinental flight. In fact, according to the International Bird Strike Committee, he was the first person to die because his airplane struck a bird: “The first fatal bird strike accident was in 1912 at Long Beach in California, when a gull (Larus sp.) lodged in the flying controls of a Wright Flyer, killing Cal Rodgers.”

A mural honoring Engine No. 34 of the obscure Streator & Clinton RR.

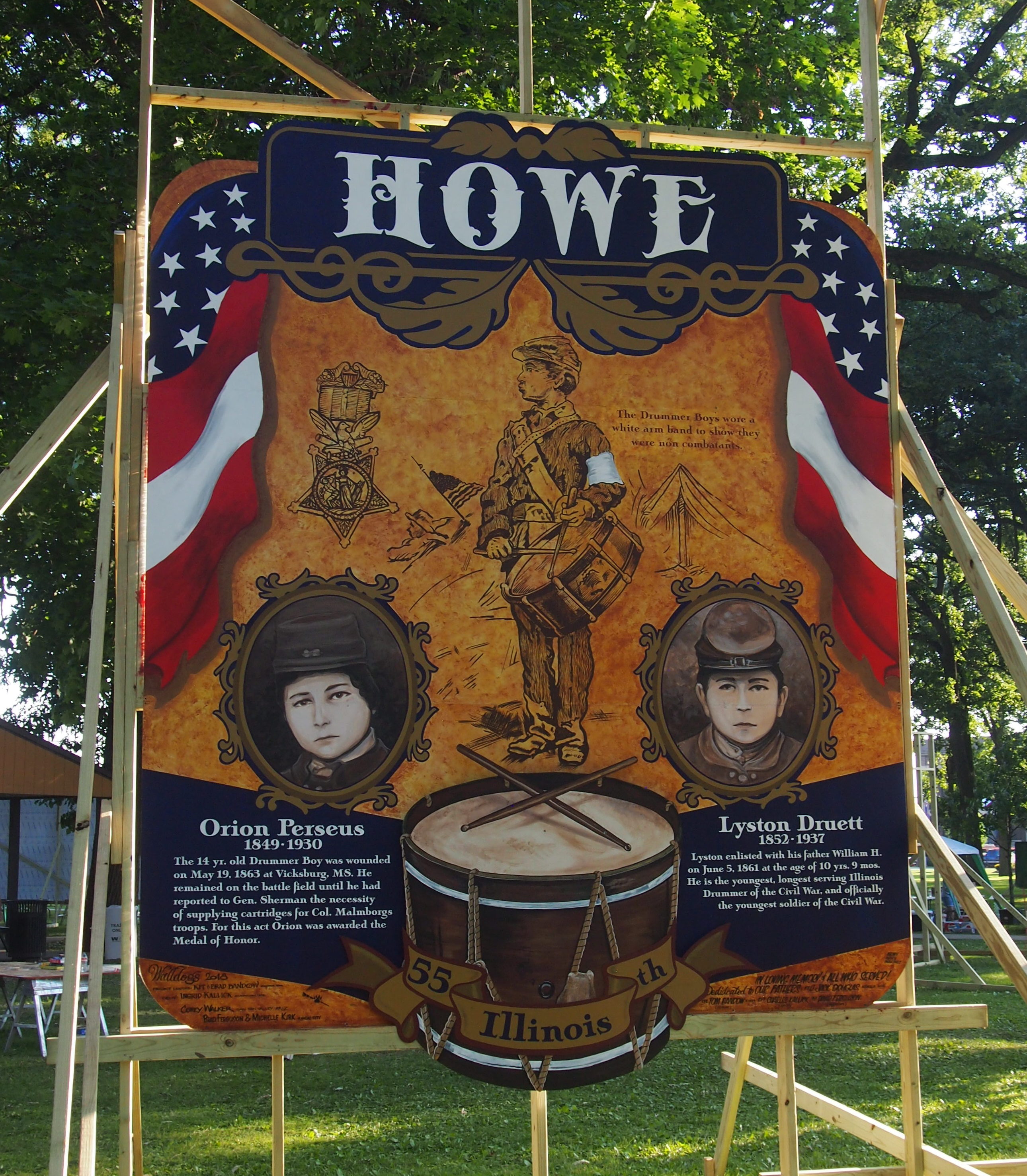

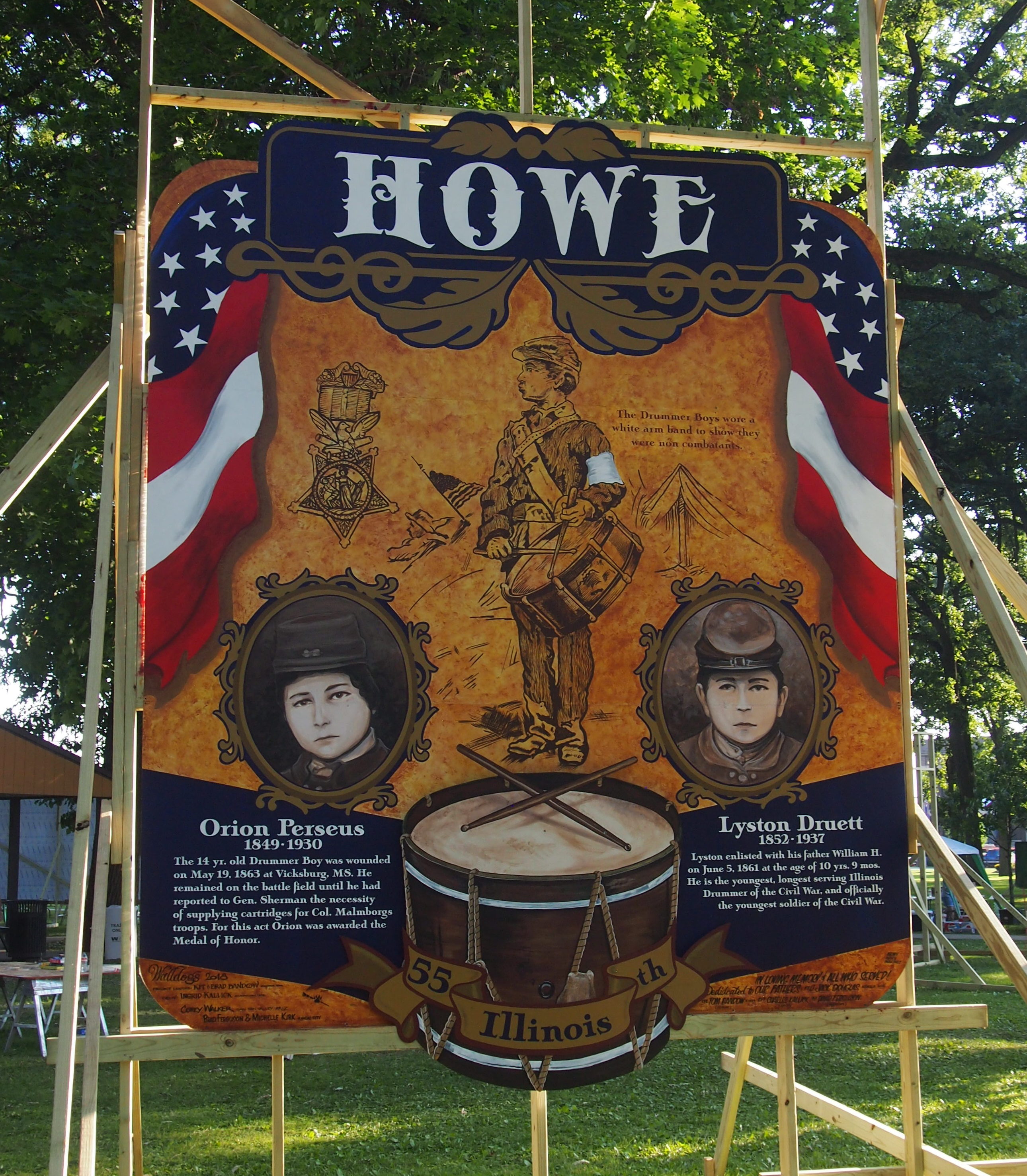

Here are the Howe brothers, Orion and Lyston.

Here are the Howe brothers, Orion and Lyston.

They were drummer boys from Streator with the 55th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Lyston has the distinction of being the youngest known drummer boy in the war, and Orion received the Medal of Honor for his conduct at Vicksburg.

They were drummer boys from Streator with the 55th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Lyston has the distinction of being the youngest known drummer boy in the war, and Orion received the Medal of Honor for his conduct at Vicksburg.

The lads have a memorial in the park, not far from where their mural was painted.

The citation for Orion says: “A drummer boy, 14 years of age, and severely wounded and exposed to a heavy fire from the enemy, he persistently remained upon the field of battle until he had reported to Gen. W. T. Sherman the necessity of supplying cartridges for the use of troops under command of Colonel Malmborg.”

The citation for Orion says: “A drummer boy, 14 years of age, and severely wounded and exposed to a heavy fire from the enemy, he persistently remained upon the field of battle until he had reported to Gen. W. T. Sherman the necessity of supplying cartridges for the use of troops under command of Colonel Malmborg.”

It did me good to know that Streator hasn’t forgotten its favorite astronomical son, a lad from the Midwest who discovered a whole planet. I bet Pluto isn’t anything but a planet to the good people of Streator. Me either.

It did me good to know that Streator hasn’t forgotten its favorite astronomical son, a lad from the Midwest who discovered a whole planet. I bet Pluto isn’t anything but a planet to the good people of Streator. Me either.

A bust of

A bust of

The exhibits include a statue of the Little Giant.

The exhibits include a statue of the Little Giant. While we were there, a group of historic re-enactors in 19th-century costumes happened to be in the recreated House chamber.

While we were there, a group of historic re-enactors in 19th-century costumes happened to be in the recreated House chamber.

This was called the Chinese Maze Garden, and I suppose it would be a challenge for people a foot tall.

This was called the Chinese Maze Garden, and I suppose it would be a challenge for people a foot tall.