The thing is, with many boxes of chocolates, you do know what you’re going to get, provided you read the box. So pay attention, Forrest.

We found a 10.9 oz. box of Godiva chocolates (27 pieces) at a warehouse store for a significant discount to that brand’s normally high prices, so we brought it home. Considering those high prices, this is a rare treat. Sure, Godiva’s really good chocolate, but so are other brands at less than premium prices.

We’ve been eating one piece each after dinner, six pieces all together so far. I’ve had the milk chocolate ganache bliss — hard to argue with a name like that — and dark chocolate coconut. Mm.

Godiva Chocolatier, incidentally, hasn’t really been Belgian in a long time. The Belgians sold it to the Campbell Soup Co., of all companies, almost 50 years ago. More recently, Campbell sold it to Yildiz Holding, a Turkish conglomerate. The brand has about 450 stores worldwide, including more than 100 in China.

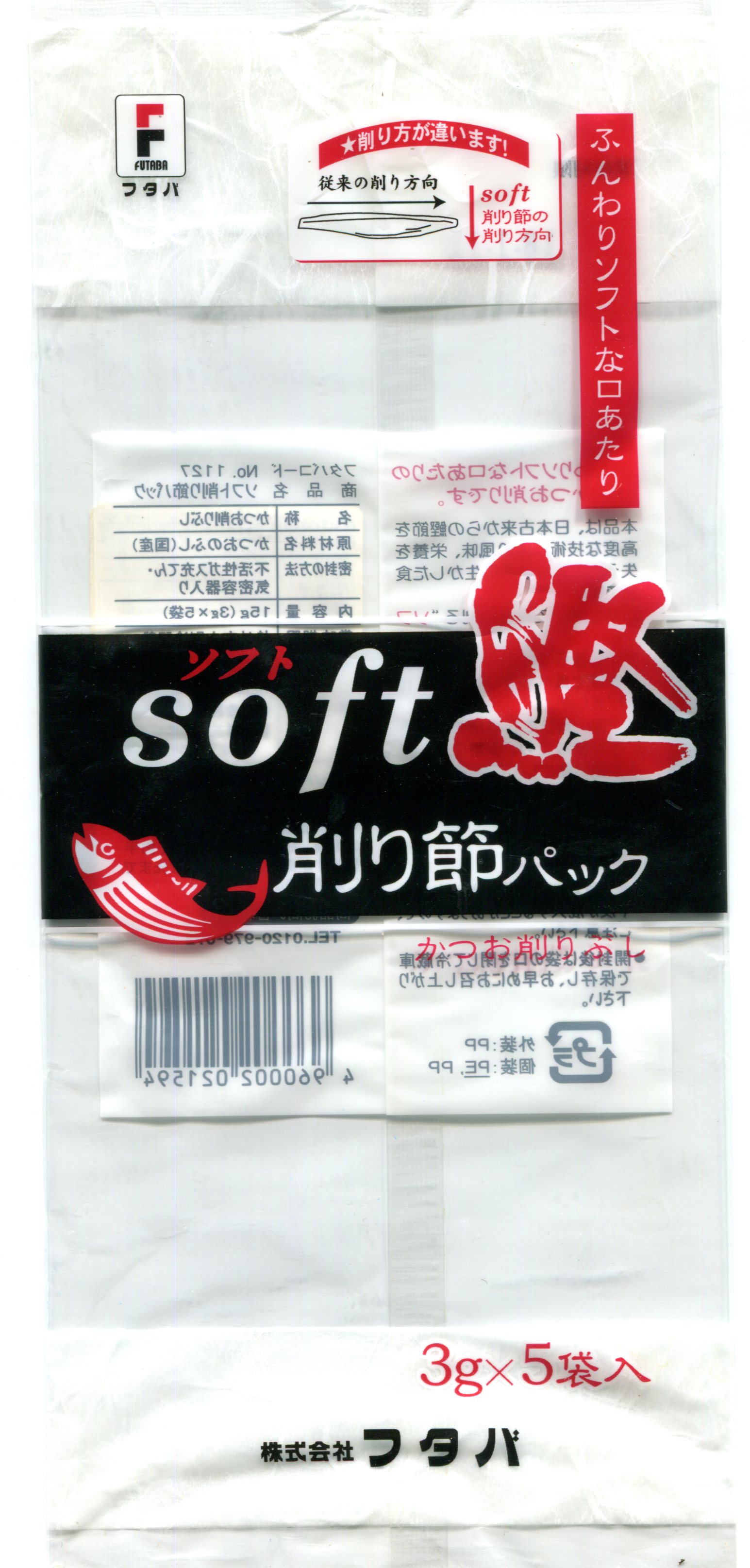

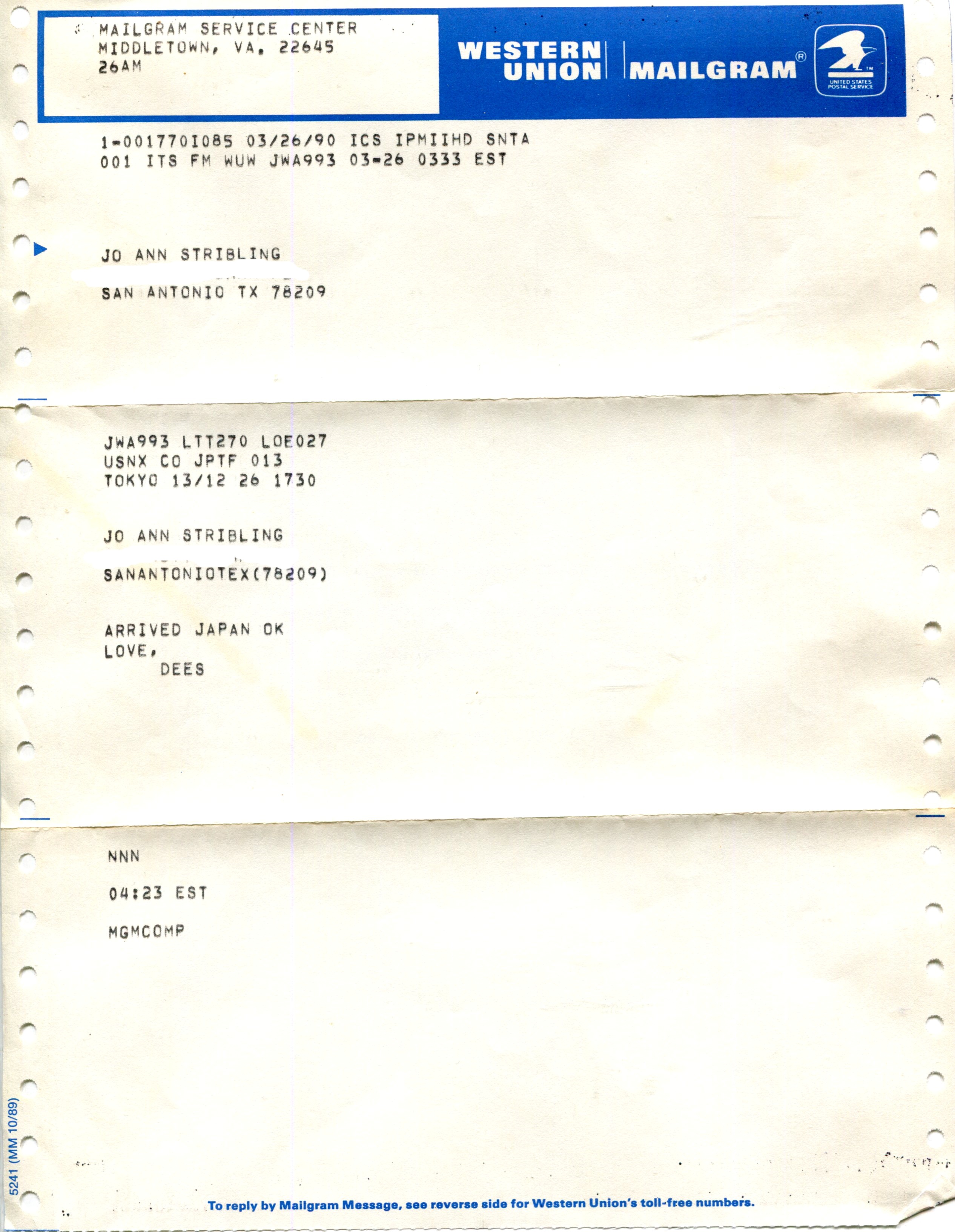

While finding that out, I also discovered that Godiva has been taking out ads in recent years in Japan against the practice of giri choco, the popular custom of Japanese women giving chocolate to men, often coworkers, on February 14. A nice example of cross-cultural WTF, but you run into that kind of thing a fair amount in Japan.

As far as I can tell, Godiva doesn’t have a beef with the practice per se, it was merely trying to annoy a Japanese competitor, Black Thunder, which seems to be popular for giri choco. I don’t have any experience with that brand, though the name amuses me. Seems it came to the market after I lived there.