On Saturday we took a quick hop over to Rockford, Ill., and soon found ourselves face-to-face with Conifer Man.

To me this looks like a guy in a tree suit – that’s how I’d guess it looks, anyway – but it’s really one of the odd-shaped conifers to be seen at the Klehm Arboretum & Botanic Garden in Rockford, which features about 500 species and cultivars of woody plants on 155 acres. Not that I would know even a fraction of those, but still I know an odd conifer when I see one.

This, for instance, is a weeping white spruce. Ann compared it to Charlie Brown’s tree.

Next, according to the sign, is a procumbent blue spruce or, as I like to think of it, a Christmas tree implosion.

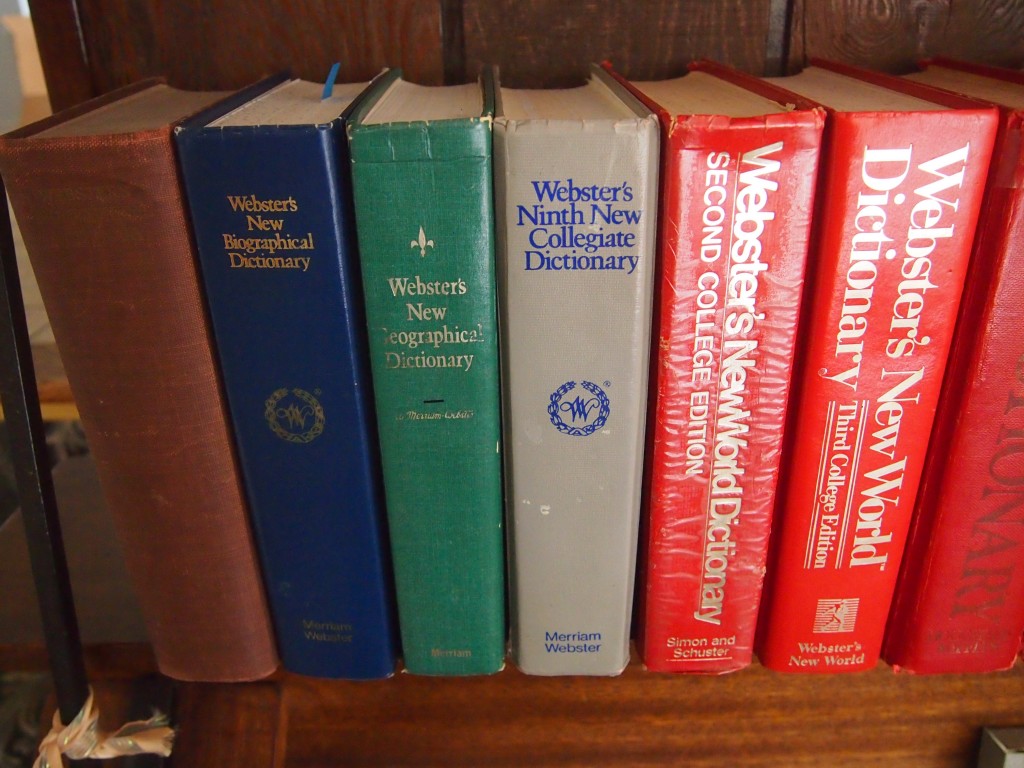

Procumbent. Now there’s a word you don’t see much, a solid Latinate that seems to be used mostly to describe plants with stems that trail along the ground without rooting. Another meaning is simply lying face down, but I’m not sure I’ve ever seen it used that way, with “recumbent” the main choice for lying down in some way. The terms accumbent and decumbent are cousin-words usually used in botany – “resting against another part” and “lying or growing along the ground, but erect near the plant’s apex,” respectively.

As long as I’m on a lingual tangent, the Latin cumbere, to lie down, goes all the way back to the Indo-European base keu-(2), which my American Heritage New College Dictionary appendix tells me is a “base of loosely related derivatives with assumed basic meaning ‘to bend.’ ” Plants certainly bend to be accumbent or decumbent or procumbent, but animals and people do as well, to some degree, so that fits.

Starting in the early 1900s, the site of the Klehm was a commercial nursery, and so it remained until 1985. The original owners planted a good many of the now-large trees, which are sometimes noticeable for being in rows. These days the land belongs to the Winnebago County Forest Preserve District, who have been busy in recent decades making the place less like a nursery and more like a woody museum.

Walk along the main path and you can’t miss the conifers, some of which are very large, unlike the oddities pictured above. Not that you can’t see the likes of pines, firs, junipers, spruces and so on elsewhere, especially as you go north, but even so the Klehm collection is impressive.

Naturally, we had such a casual visit that we missed some of the more remarkable trees – which I read about later – such as the grove of Bur oaks that were there before the nursery, and which might be as old as a pre-settlement 300 years. There are also some fully grown American chestnut trees on the grounds, which I understand are pretty rare, since an invasive blight destroyed most of that species in the 20th century.