I asked Ann about both Buddy Holly and Will Rogers not long ago. She was unfamiliar with them. That only goes to show a generational difference. As far as I’m concerned, both are visible threads in the American cultural fabric, people I always remember hearing about. But the tapestry is very large and changing, so every generation sees different threads.

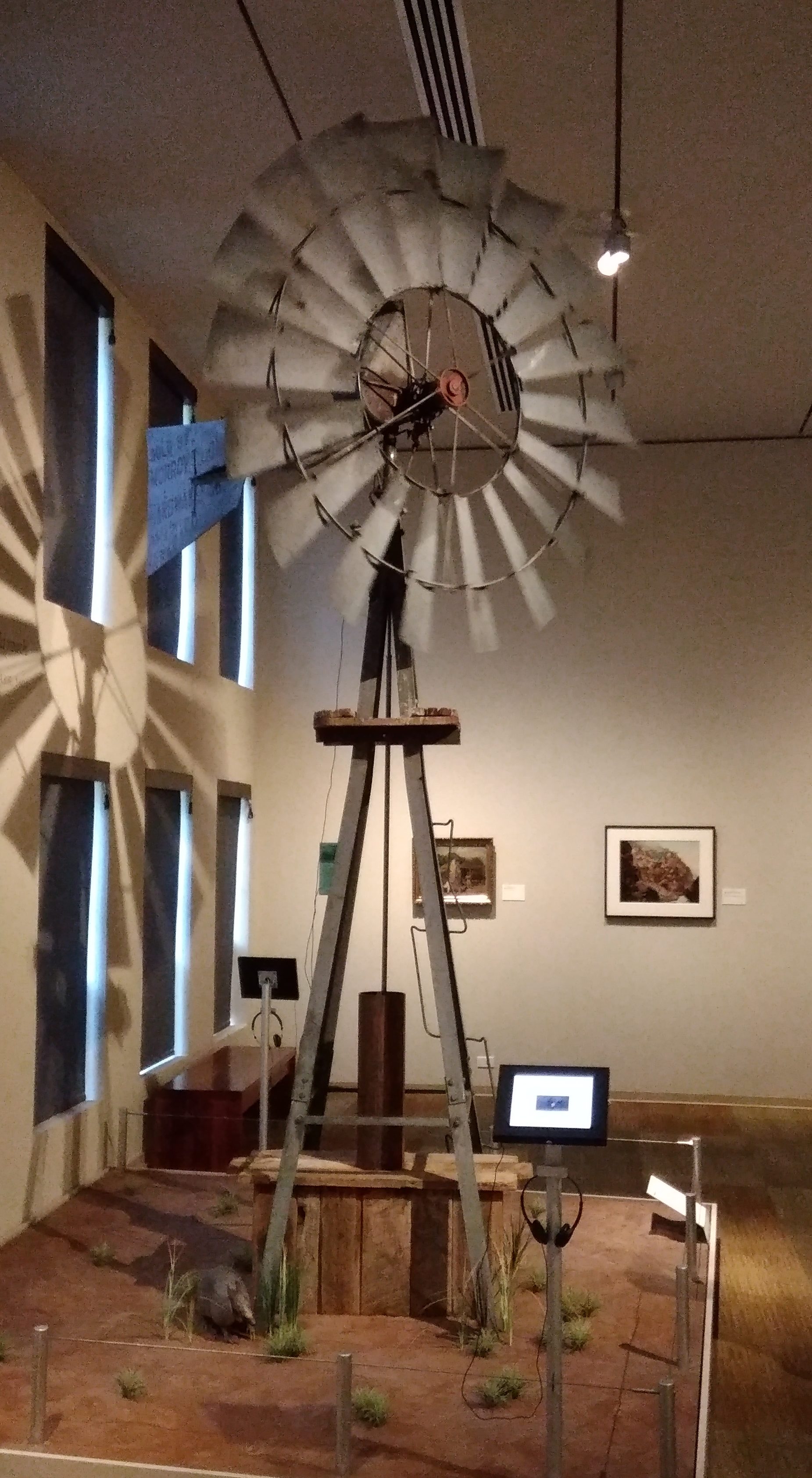

While driving from Marathon, Texas, to Amarillo, I passed through Lubbock, a city I’d had scant experience with before. Maybe none, I’m not sure. So I took a short look around. If I’d had more time, I might have strolled around the campus of Texas Tech or visited the American Wind Power Museum or the Prairie Dog Town at Mackenzie Park.

But I only wanted to spend a few hours in town, so I made my way to the Buddy Holly Center.

The center, which is at 1801 Crickets Ave., and a block from Buddy Holly Ave., is a performing and visual arts venue that also includes a small museum dedicated to the rock ‘n’ roll pioneer from Lubbock whose surname was actually spelled Holley. The museum takes up two rooms. Really one and a half, since one room is more about other famous musicians and entertainers visiting the center, such as Sir Paul McCartney, who played a concert there in 2014 (and who, last I heard, owns the rights to Holly’s songs).

The center, which is at 1801 Crickets Ave., and a block from Buddy Holly Ave., is a performing and visual arts venue that also includes a small museum dedicated to the rock ‘n’ roll pioneer from Lubbock whose surname was actually spelled Holley. The museum takes up two rooms. Really one and a half, since one room is more about other famous musicians and entertainers visiting the center, such as Sir Paul McCartney, who played a concert there in 2014 (and who, last I heard, owns the rights to Holly’s songs).

Still, I will say that the main exhibit room, which is guitar-shaped, was packed with items and full of things to read. Buddy Holly might have died at 22, and only worked for a few years as an up-and-coming professional musician, but he was busy. He wrote songs, made records, toured constantly, appeared a few times on TV, and somehow found time to get married. Clearly he’d found something he was good at — this new music genre — and went after it with great energy, creating a remarkable output in a short time.

On display are photographs, letters, post cards, tour itineraries, including one for the Winter Dance Party, recording equipment, a microphone, business cards, contracts, performing outfits, furniture, Buddy’s childhood record collection (all 45s), and his Fender Stratocaster, which is the last one he ever played. There’s a lengthy timeline posted on the wall detailing Holly’s life and career, and other one about the evolution of rock ‘n’ roll.

Also on display, oddly enough, are the horn-rimmed glasses he was wearing when he died. Apparently they were in an evidence locker in Cerro Gordo County, Iowa, until 1980. The 750-pound giant glasses outside the center were fashioned in 2002 by a local artist, Steve Teeters, who died a few years ago.

No photography allowed in the museum. The clerk who sold me my ticket, and signs in the display room, were clear on that point. Something about copyright. No doubt the RIAA would release flying monkeys to snatch the camera away from anyone foolish enough to take pictures, and bill him $10,000 per image besides.

You can, however, take all the exterior shots you want, including across the street at an eight-and-a-half foot bronze of Buddy and his Fender Stratocaster, created in 1980 by San Angelo-born sculptor Grant Speed, well before the Buddy Holly Center opened in 1999. The statue was moved from elsewhere in Lubbock only a few years ago, and now fronts a wall with various plaques honoring 30 years of inductees on the West Texas Walk of Fame.

I recognized only a handful of names on the wall besides Holly, such as Waylon Jennings, Mac Davis, Tanya Tucker, Roy Orbison (who lived in Wink when he was young) and Dan Blocker, whose alma mater, Sul Ross State University, I drove by in Alpine.

The Buddy Holly Center is an adaptive reuse. Long ago, the building was a handsome depot for the Fort Worth and Denver South Plains Railway Co., dating from the 1920s.

En route from Amarillo to Lebanon, Missouri, I made a stopover in Claremont, Oklahoma, not far from Tulsa, to visit the Will Rogers Memorial Museum. Strictly speaking, I’d been there before sometime as a child. But I had no memory of it.

En route from Amarillo to Lebanon, Missouri, I made a stopover in Claremont, Oklahoma, not far from Tulsa, to visit the Will Rogers Memorial Museum. Strictly speaking, I’d been there before sometime as a child. But I had no memory of it.

Will Rogers, on the other hand, I’ve always seem to have known about. That’s remarkable for an entertainer who wasn’t actually of my parents’ time — my mother wasn’t quite 10 when he died — but rather of my grandparents’ time. I knew enough about him to go see James Whitmore do his fine impression of Rogers live, including a rope trick or two, on one of the Vanderbilt stages in the summer of 1984 .

Here’s the view of the museum from the back. John Duncan Forsyth designed the original 15,000-square-foot limestone building, though there was an addition in the 1980s.

Will Rogers has a good many more exhibits than Buddy Holly, as you’d expect, considering that Rogers’ career in entertainment lasted quite a bit longer, beginning with wild west shows when that was still a thing, and moving on to all the media available in the first decades of the 20th century: vaudeville, movies, radio, and newspapers. No doubt if Rogers had lived on into the 1950s — he was only 55 when he died — we’d remember an early TV program called The Will Rogers Show.

Will Rogers has a good many more exhibits than Buddy Holly, as you’d expect, considering that Rogers’ career in entertainment lasted quite a bit longer, beginning with wild west shows when that was still a thing, and moving on to all the media available in the first decades of the 20th century: vaudeville, movies, radio, and newspapers. No doubt if Rogers had lived on into the 1950s — he was only 55 when he died — we’d remember an early TV program called The Will Rogers Show.

Before I went to the museum, I had only the vaguest notion of Rogers’ early life in the Oklahoma Territory. I imagined that his origins were quite modest. Probably he was happy to have people think that, but in fact his father, Clem Rogers, was quite prosperous. The museum hints that Clem considered his son something of a ne’er-do-well, slumming as a cowboy and lassoist.

The last laugh was on Clem, who died before his son got into movies or on the radio. Ultimately, Will Rogers built himself a 31-room ranch house in California, which (per Wiki) “includes 11 baths and seven fireplaces, is surrounded by a stable, corrals, riding ring, roping arena, golf course, polo field — and riding and hiking trails that give visitors views of the ranch and the surrounding countryside — 186 acres.”

When the nation loves you, you can afford such digs. Here’s what President Roosevelt said over the radio in 1938 to dedicate the memorial in Claremore: “This afternoon we pay grateful homage to the memory of a man who helped the nation to smile. And after all, I doubt if there is among us a more useful citizen than the one who holds the secret of banishing gloom, of making tears give way to laughter, of supplanting desolation and despair with hope and courage. For hope and courage always go with a light heart.

“There was something infectious about his humor. His appeal went straight to the heart of the nation. Above all things, in a time grown too solemn and somber he brought his countrymen back to a sense of proportion.”

Rogers, his wife, three of his children and one of his grandchildren are interred on the grounds.

Naturally, there’s an equestrian statue of Rogers on the grounds.

Naturally, there’s an equestrian statue of Rogers on the grounds.

It’s now near the tomb. To judge from the ca. 1970 picture I posted a few years ago, the statue has been moved from wherever it was then. The view from the back of the museum:

I didn’t take too many pictures inside the museum, but I make an image of a painting I liked.

It’s by an artist named John Hammer, who lives in Claremore. (More about him here.) I knew his style at once, since about a year ago I saw an edition of Travel Buddy — a coupon book you get at rest stops — that had a painting of his on the cover, a portrait of another Okie of renown, Woody Guthrie.

It’s by an artist named John Hammer, who lives in Claremore. (More about him here.) I knew his style at once, since about a year ago I saw an edition of Travel Buddy — a coupon book you get at rest stops — that had a painting of his on the cover, a portrait of another Okie of renown, Woody Guthrie.

I picked it up because it was so different that anything you might see on a publication like that. I kept it because I really liked it.

V.H. McNutt was a mining engineer who made a fortune in potash in New Mexico in the 1920s. Later he and his wife owned a large ranch near San Antonio. The McNutt Foundation is in San Antonio even now.

V.H. McNutt was a mining engineer who made a fortune in potash in New Mexico in the 1920s. Later he and his wife owned a large ranch near San Antonio. The McNutt Foundation is in San Antonio even now. “Bird Woman” (2001) by Richard Greeves.

“Bird Woman” (2001) by Richard Greeves. “Rainmaker” (1998) by John Coleman.

“Rainmaker” (1998) by John Coleman. “Dance of the Eagle” (1986) by Allan Houser.

“Dance of the Eagle” (1986) by Allan Houser. Quanah Parker had a prominent place at the small museum at Palo Dura Canyon State Park that I visited earlier this year. He was one of the leaders the last of the Comanches’ big raids, the Battle of Adobe Walls, in 1874.

Quanah Parker had a prominent place at the small museum at Palo Dura Canyon State Park that I visited earlier this year. He was one of the leaders the last of the Comanches’ big raids, the Battle of Adobe Walls, in 1874. And a detail from “El Caporal” (2015) by Enrique Guerra.

And a detail from “El Caporal” (2015) by Enrique Guerra. Detail because he appears to be driving some bronze cattle, not pictured here, ahead of him.

Detail because he appears to be driving some bronze cattle, not pictured here, ahead of him.

The museum says, ” Built in 1913, this ‘menagerie’ carousel’s hand-carved animals include storks, goats, zebras, dogs, and even a frog. Although its original location is uncertain, this carousel operated in Spokane, Washington, from 1923 to 1961.”

The museum says, ” Built in 1913, this ‘menagerie’ carousel’s hand-carved animals include storks, goats, zebras, dogs, and even a frog. Although its original location is uncertain, this carousel operated in Spokane, Washington, from 1923 to 1961.”