“This is for the birds,” I said.

There was context for it, but first the setting: we were on the sidewalk on Calle Londres in the Coyoacan neighborhood of Mexico City early in the afternoon of December 29, just outside the Museo Frida Kahlo.

Curiously, besides a street named after London in the area, there were also calles Bruselas, Madrid, Viena, Berlin, and Paris: European capitals. Unlike the part of the Zona Rosa where our hotel was, which had streets named after European cities, capitals and non-capitals: Londres and Berlin (again), but also Roma, Liverpool, Marsella, Hamburgo, Napoles, Oslo.

Coyoacan is a pleasant walking neighborhood, sporting mature trees, sidewalks in reasonably good shape — with not as much pedestrian traffic as in other parts of town we frequented — and large, colorful houses. After a while you do notice that some of the larger houses are essentially walled compounds with iron-bar accents and hard-to-see entrances. Ah well, así es la vida in the big city, if you’re well-to-do.

The most famous compound is the Casa Azul at Londres 247, and blue it is. A deep blue. Like a lot of people, we wanted to visit Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s house. A whole lot of other people, as it turned out. After we got there, we waited a few minutes in one line, only to discover that was the line for people who already had tickets. So we then joined the equally long line to buy tickets.

We’d been advised to buy tickets ahead of time. We ignored that advice. After a few minutes standing in the non-moving ticket-buying line, and with the knowledge that we’d have to stand in another such line eventually, I said waiting was for the birds. Everyone else agreed. No go on Museo Frida Kahlo.

I’m sure the Casa Azul is an excellent museum, but I suspect the real reason for the overcrowding is the movie Frida, which came out in 2002. Her artistic reputation had already been rising, such that Diego Rivera is now her husband, rather than Frida Kahlo being his wife, but I believe the movie kicked it into high gear, the way Nashville has overcrowded the Bluebird Cafe.

Luckily, we had another nearby destination in mind anyway: the Casa de Leon Trotsky. Who could resist that? Not only were Frida and Diego part of the story, it’s got international intrigue, murderous foreign operatives, adultery, a gun battle led by another famous artist, genuine communists and communist plots, and — the crowning event, you might say, an axe murder!

Clearly, Trotsky needs the Hollywood treatment (besides this) if the museum wants to get people in the door, you know, the sort of people who never really heard of that guy Trotsky until they saw that movie about him. Then again, crowds would have drained the fun out of the experience. The Trotsky House wasn’t deserted by any means. A fair number of people were there. But we didn’t have to wait for tickets and crowds didn’t get in the way of free movement around the place, with one exception.

Casa de Leon Trotsky, I’m delighted to report, is quite red on the outside. The present-day complex includes what must have been the building next door at one time, which you enter through and which now has exhibits devoted to the Bolshevik leader. From there, visitors go to a small but very pleasant courtyard with an assortment of plants, walking paths and a few benches.

I don’t know how well tended the garden was in Trotsky’s time, though he did raise chickens and rabbits there. But I do know there was one feature Trotsky never saw himself.

Namely, Trotsky’s grave, where his and Natalia Sedova’s ashes are interred (she died in 1962). Naturally, I couldn’t resist the joke: it’s commie plot. I think I heard that one as long ago as high school, only it was about Stalin’s grave (Lenin and Mao and Ho, strictly speaking, have no graves).

Namely, Trotsky’s grave, where his and Natalia Sedova’s ashes are interred (she died in 1962). Naturally, I couldn’t resist the joke: it’s commie plot. I think I heard that one as long ago as high school, only it was about Stalin’s grave (Lenin and Mao and Ho, strictly speaking, have no graves).

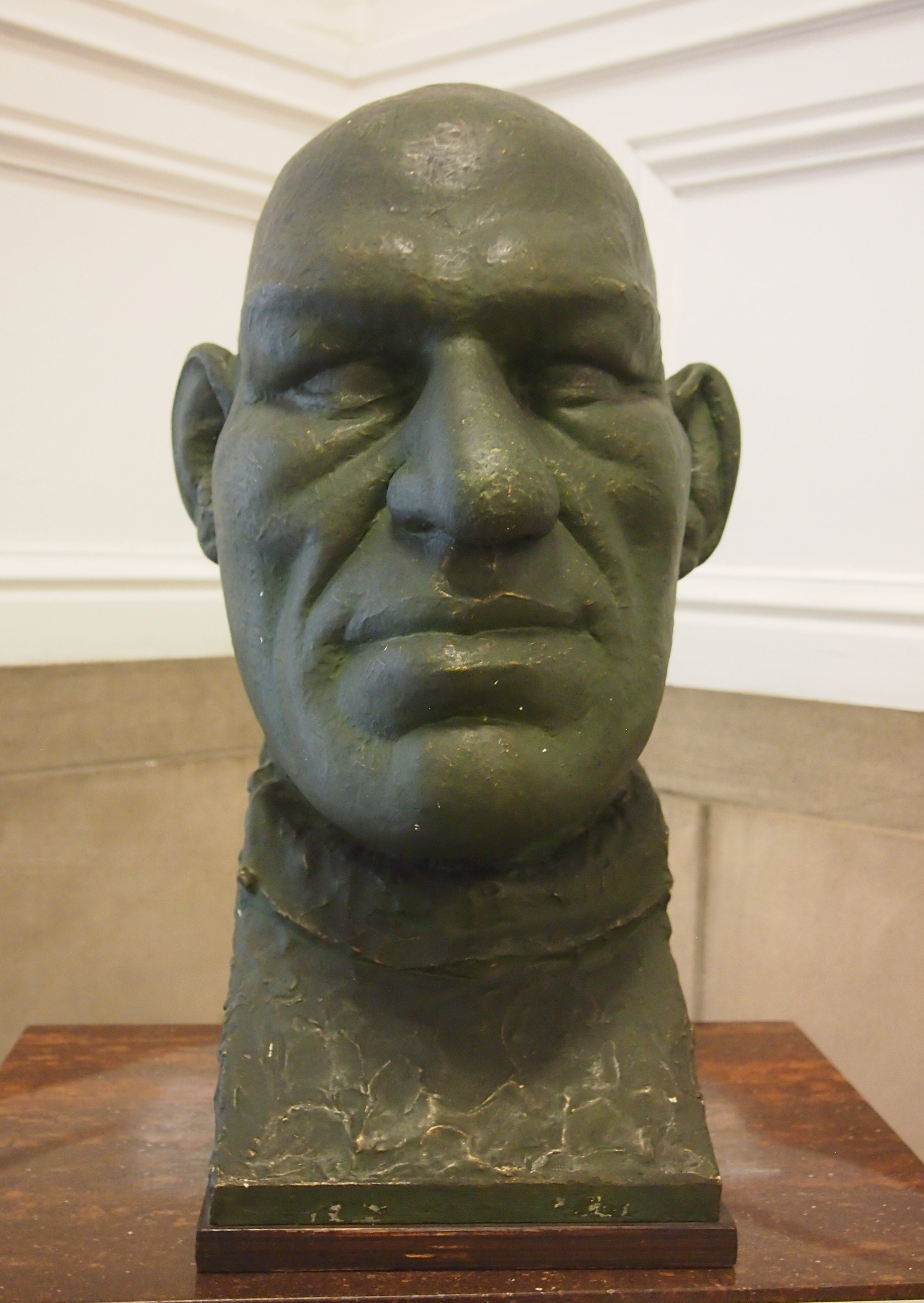

Behind the grave site is the house itself and an attached guard house, for all the good it did Trotsky. The first floor of the guard house has a few more exhibits, including photos of Trotsky at various ages and other family members, as well as a family tree. For all of Stalin’s efforts to murder Trotsky’s offspring too, the revolutionary has quite a few living descendants, including in Mexico, the United States and Russia.

The axe wasn’t on display anywhere. That’s because it isn’t even in Mexico.

The house is fairly modest and solidly built, with thick walls and bullet holes on the outside of one of the walls, purportedly left by the unsuccessful May 1940 attempt on Trotsky’s life led by David Alfaro Siqueiros. We saw some of Siqueiros’ murals later, as one does in Mexico City. That Stalinist episode of attempted murder hasn’t seemed to have harmed his reputation as an artist.

Trotsky had reason to be security-conscious, and the compound reflects it. Besides the guardhouse, which includes a guard tower, the entire residence is surrounded by thick walls. Its doors are heavy and, at least going into Trotsky’s study, re-enforced with iron. I didn’t see any steel window shutters or barbed wire, but I read these were part of the security too. None of that stopped a determined NKVD agent with an ice axe.

The study itself is supposedly the way Trotsky left it: a large desk, a lamp, chairs, papers and books, a Dictaphone, a small bed on which to rest (see the picture here). The floor, I noticed, is painted red. It was here that moving around was a little constrained, since you can only stand in a small part of the room, like in most house museums, and visitors want to see the study most of all. I know I did.

The current setup at Trotsky’s House includes a small cafe next to the guardhouse. We had a light lunch al fresco there, cheese crepes for me, and some of the best orange juice I’ve had in a long time. All in all, a bourgeois sort of meal. I expect the waiter was paid for his efforts and presumably the museum made a modest amount, which it probably needs to keep the lights on.

The museum also features a small gift shop at the entrance, heavy on socialist books and portraits of Trotsky for sale and light on tourist gimcracks, though I bought some postcards there. I doubt that the organization is using any of its budget to foment worldwide socialist revolution.

A little more than a century later, it was the site of the little-known Battle of Concepción in the Texas Revolution.

A little more than a century later, it was the site of the little-known Battle of Concepción in the Texas Revolution. Mission San Jose.

Mission San Jose. In full, Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, with construction starting in the 1760s, and restored by the WPA in the 1930s.

In full, Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, with construction starting in the 1760s, and restored by the WPA in the 1930s. It’s still an active church.

It’s still an active church. Mission San Juan Capistrano.

Mission San Juan Capistrano. The church building had just been renovated the year before, which accounts for its newish, rather than long-weathered look.

The church building had just been renovated the year before, which accounts for its newish, rather than long-weathered look. We didn’t make it to Mission Espada, and I haven’t been back that way since. Maybe one of these days.

We didn’t make it to Mission Espada, and I haven’t been back that way since. Maybe one of these days.