Around this time of the year 34 years ago, I spent a couple of days in the north German city of Bremen. City-state, actually: Freie Hansestadt Bremen, the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen. Once a state in the German Confederation, then a component state of the German Empire, it was merely a city according to the Nazis. Since 1947, it’s been a state again, the smallest in area of the Federal Republic.

Odd, Bremen and Hamburg got to be states again, but not poor old Lübeck. Such are the vagaries of history.

I had a fine time. How could I not? I was a young man with exactly nothing else to do at that moment but see a new city in an interesting old country. I was a free man in Bremen/I felt unfettered and alive… Well, that lyric wouldn’t have quite the same vibe, but that’s not too far off. Anyway, my tourist impulse was in full flower.

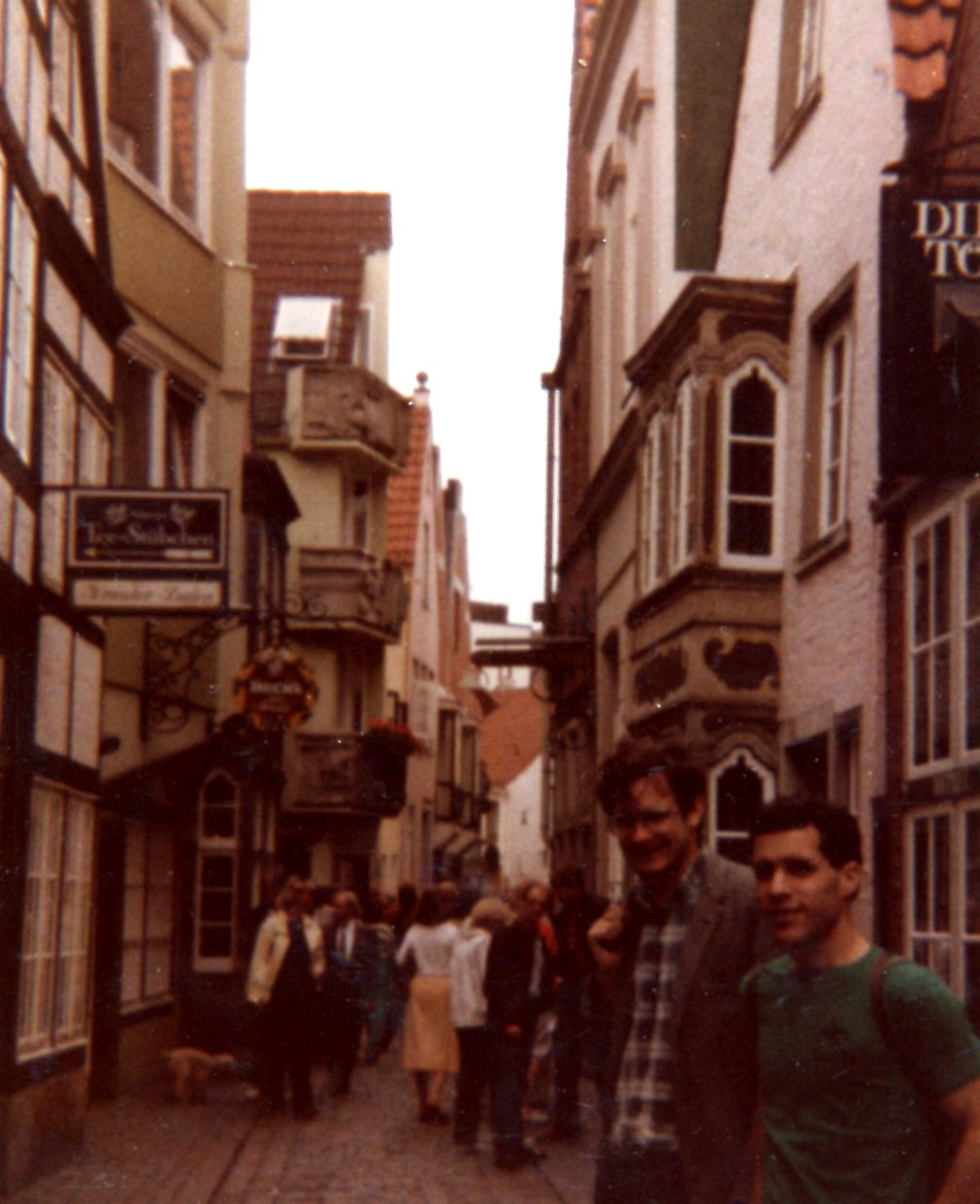

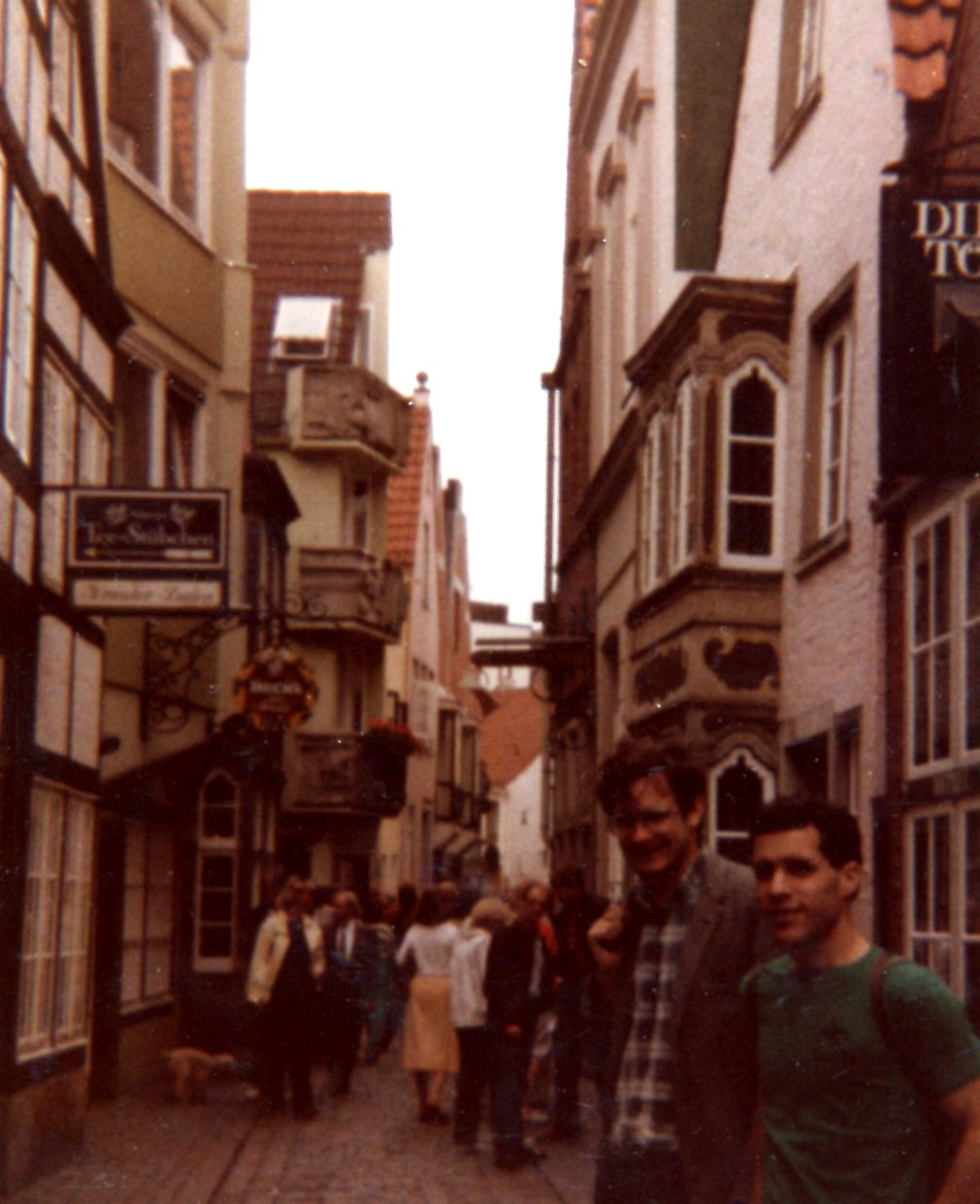

This is David and me. He was the brother of a New Yorker friend of mine in Germany, Debbie. Mostly I was by myself in Bremen, but I met up with them toward the end of my visit. The background is the Schnoor, more about which later.

The following is an edited version of what I wrote at the time.

The following is an edited version of what I wrote at the time.

“At Bremen I exited the station, got a map, and experienced the first-time rush of a new place. You aren’t tired, you feel open to the world, you want to look at everything you pass by. I crossed downtown Bremen’s large fussgangerplatz, walked by shops and goods and people, and enjoyed the sights and sounds. That kind of rush doesn’t last long, but it’s great while it does.

“I found the Jugendherberge, an ugly squarish building between downtown and the industrial Weser riverside. Check-in wasn’t until 1:30, so I sat under a bridge near St. Stephen’s and ate the bread and wurst I brought. The brot was a little dry and the wurst something like raw hamburger, but I needed the sustenance.

“Then I checked in and began wandering. I found the Rathaus first, then the famous 1404 statue of Roland. I spent a good while in Bremen Cathedral (St. Petri Dom zu Bremen), marveling at its intricate, aesthetic wonders, such as the painted pillars and the statues illustrating the Parable of the Ten Virgins. Went to the crypt, thought to be the oldest room in Bremen, dedicated in 1066.

“Sometimes I mulled a bit gloomily that time will sooner or later reduce the cathedral to dust — via nuclear attack in August or 10,000 years of erosion or something. But it’s here, now, and so am I. Before I left, I bought a little book about the cathedral.

“Not long after I left, I spotted a series of white dots painted on the sidewalk, with the words Zum Schnoor –> every 30 or 40 feet to go with them. I followed them to the Schnoor. I’d heard that the Schnoor was the oldest surviving section of the city, and so it seems. The Schnoor is focused on a narrow street of that name, lined with aged shops and other buildings. Some of the side streets are even narrower, barely wide enough for two people to pass.

“Not long after I left, I spotted a series of white dots painted on the sidewalk, with the words Zum Schnoor –> every 30 or 40 feet to go with them. I followed them to the Schnoor. I’d heard that the Schnoor was the oldest surviving section of the city, and so it seems. The Schnoor is focused on a narrow street of that name, lined with aged shops and other buildings. Some of the side streets are even narrower, barely wide enough for two people to pass.

“En route to a church I never got into because it was always locked, I came across Böttcherstraße. Every ten feet or so is another work by one Bernhard Hoetger, some interesting stuff dating from pre-you-know-who Weimar years. Apparently the Nazis didn’t much like the works, but they survived them and the war. [Brick Expressionism, I’ve read, is the term, at least for some of the buildings.] There was also a small cinema tucked away in the area. Showing that evening: Death in Venice. An Italian movie with German subtitles, probably, or dubbed in German. I decided not to go.

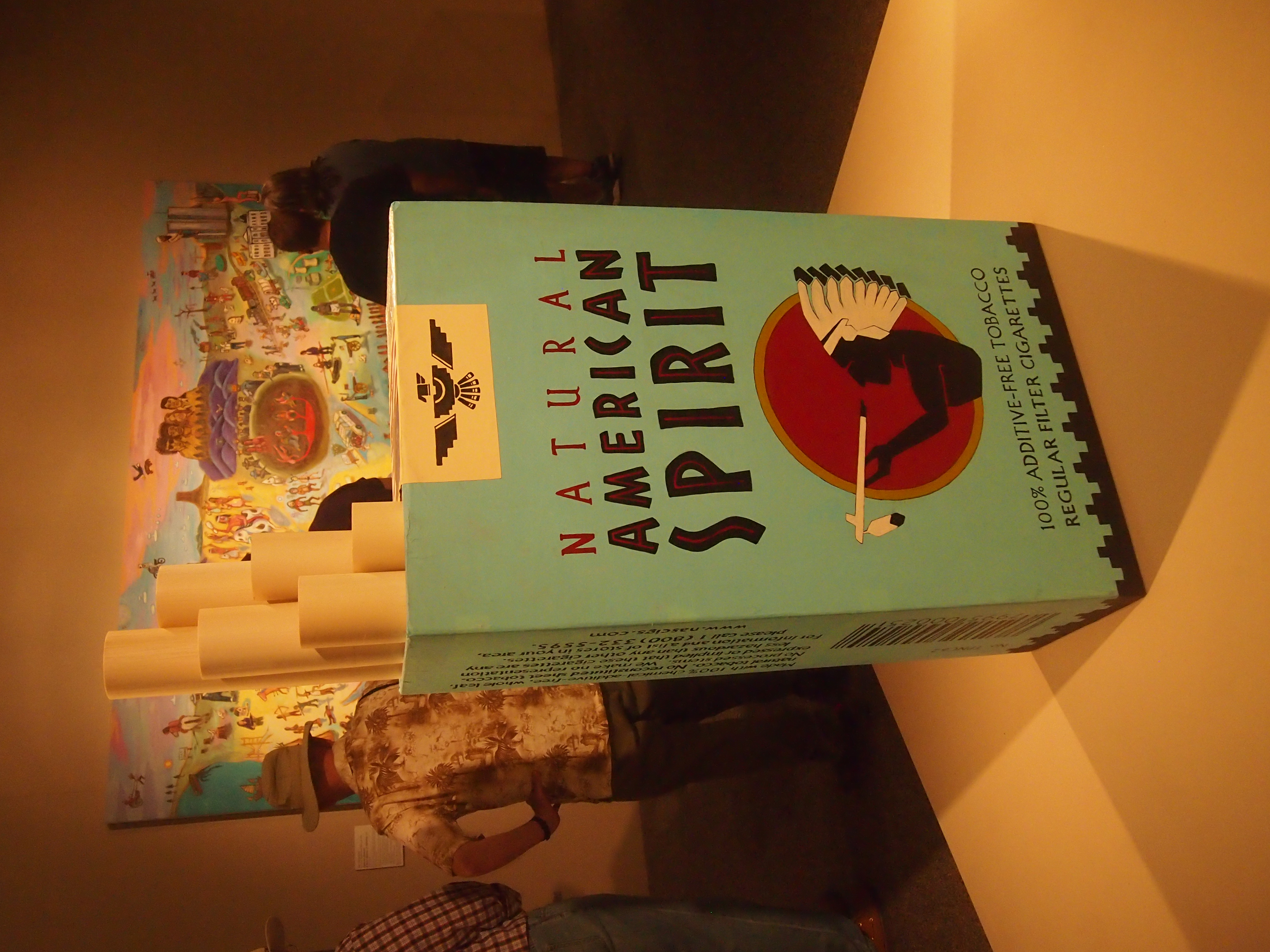

“I walked further afield, near some small city lakes, and then to the Übersee Museum Bremen, near the main train station. It’s an ethnographic museum, complete with huts from New Guinea, a Japanese shrine with a manicured garden and a pond with goldfish, and a elegant Burmese temple. All of the labels were in German, but that didn’t matter much [I experienced something similar some years later at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka.]

“There was a special exhibit of schoolchildren’s paintings: ‘Japanese kids see us and German kids see Japan.’ A funny mix of cultural and political images, mostly, tending toward the stereotypical. My favorite was a Japanese drawing of a German with a grinning Volkswagen for a head, eating sausage and drinking beer. Hitler’s face and swastikas were common, as was Beethoven’s face, and some drawings showed Germany torn between the Stars & Stripes and the Hammer & Sickle.

“After the museum I had dinner at the Restaurant Belgrade. For DM 16, I had an excellent Hungarian goulash, potatoes, salad, bread and beer. Returned to the hostel at about 10, very tired, and went to sleep almost at once.

“At breakfast at the hostel I talked with a Japanese girl who’d been to the Bremen Geothe Institut and who was about to go home. She was pleasant, and showed me postcards of Japan. After checking out, I wandered the streets on the other side of the Weser a while, then at 10 took a harbor cruise.

“It was a busy place, with ships from all over, and vast industrial areas along the banks, including a huge drydock belonging to Krupp, and a Kellogg’s factory with enormous murals of Tony the Tiger and Snap, Crackle & Pop on its side. I couldn’t catch a lot of the narration, but it seemed mostly about ship sizes and carrying capacities, so I didn’t mind.

“Back on land, I visited the church opposite the Dom, Unser Lieben Frauen Kirche, the second-oldest church in the city, and not as ornate as the cathedral. I took a tour of the Rathaus, and as Steve promised, the place has remarkable woodwork. For example, the puti-like faces on some of the chairs managed to have lustful and leering expressions. The Rathaus also has a fine collection of model ships, mostly the 17th-century Bremen fleet, and an assortment of portraits of Holy Roman Emperors.

“As if that wasn’t enough, I then went to the Ludwig Roselius Museum, which houses paintings & furniture & gold & maps from the 17th and 18th centuries. Saw the original black painting of Martin Luther that I’ve seen reproduced a number of other places [Lucas Cranach].

“My energy was low by this time, but I walked some more, returning to the Böttcherstraße at 3 and hearing the chimes of the Glockenspiel House and seeing the rotating woodcarvings of explorers and airmen. Met Debbie and David soon after, and we repaired to a nearby cafe for beer. They’d been there the day. Returned to Lüneburg soon after on a faster direct train, and had dinner together at another Yugoslav restaurant. For DM 14, got Serbian combo of meat, rice and beans, along with beer.”

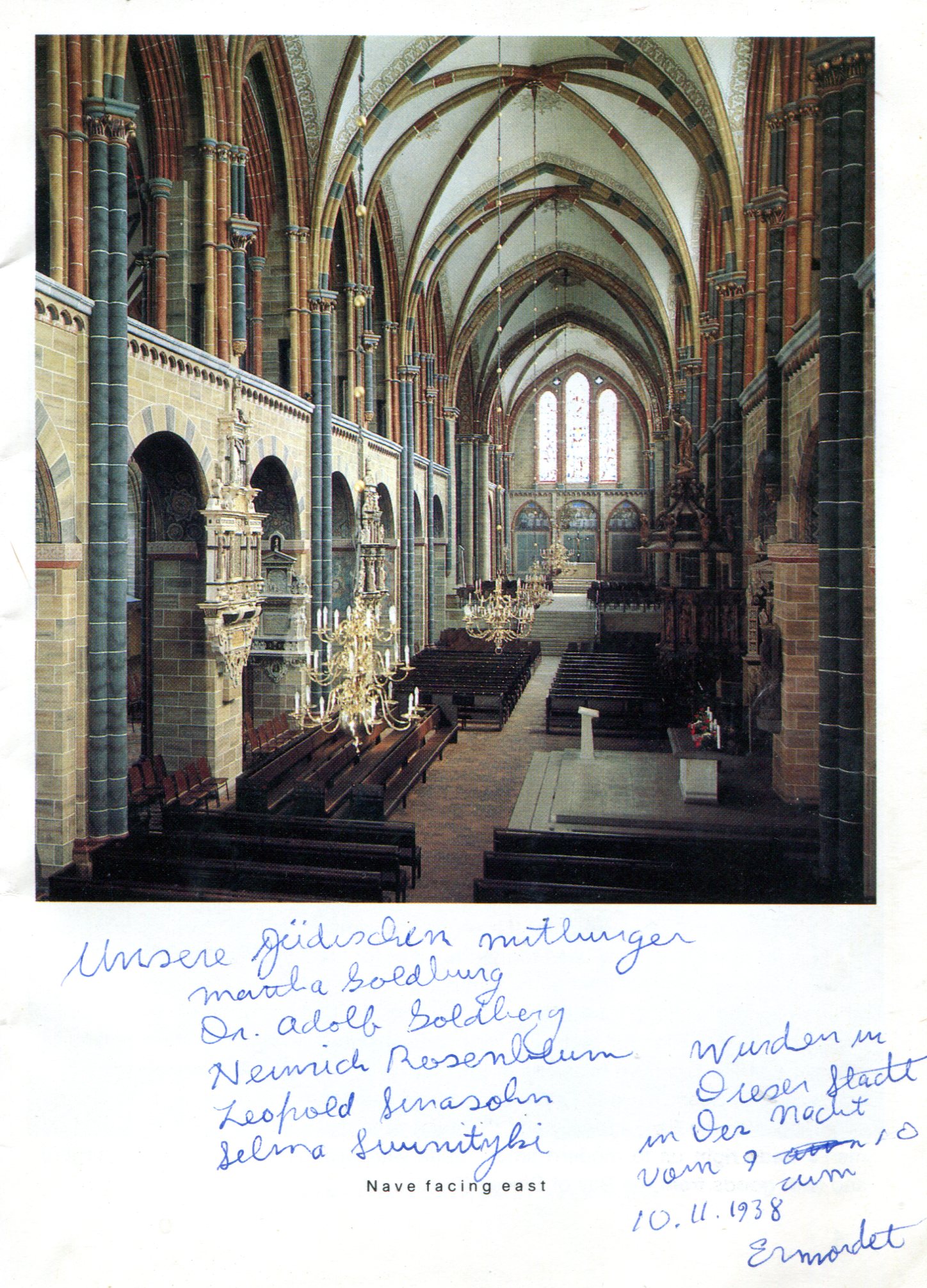

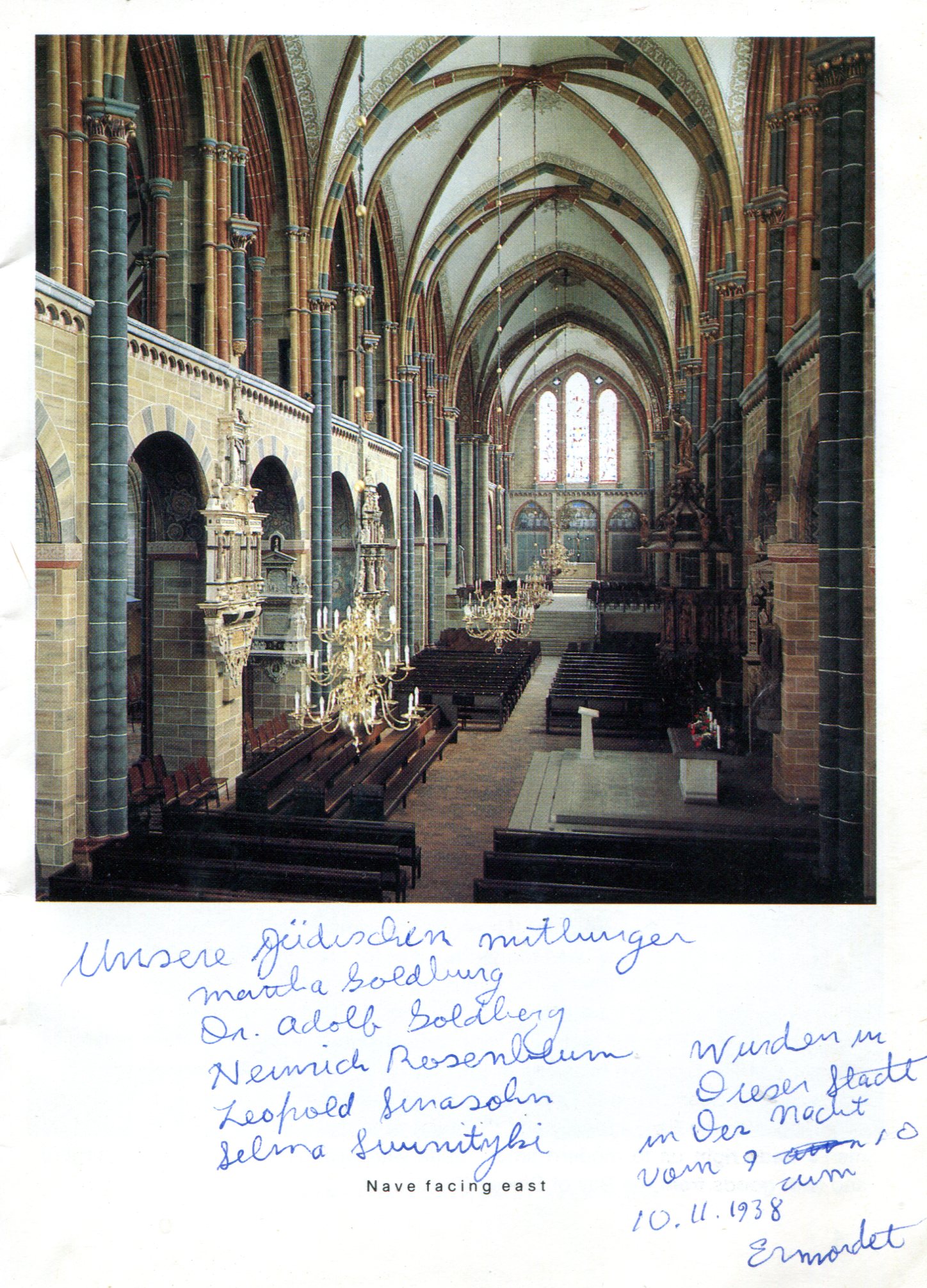

One more thing. In Bremen, near the Schnoor, I found a memorial I didn’t expect. I made notes about it in my Bremen Cathedral book, which is what I had at hand.

Unsere Jüdischen mitbürger

Unsere Jüdischen mitbürger

Martha Goldberg

Dr. Adolf Goldberg

Heinrich Rosenblum

Leopold Sinasohn

Selma Swinitzki

Wurden in dieser Stadt in der Nacht vom 9. zum 10.11.1938 ermordet.

Murdered during Kristallnacht, in other words. This is what the plaque looks like. Remarkably, Adolf Goldberg has a Wiki page, which also tells me that the memorial was erected in 1982, only a short time before I saw it.

Mounted, I’m sure, to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the revolution. Just inside the entrance to the exhibit was the “Lenin Wall.” Lots of Lenin, including a small statue.

Mounted, I’m sure, to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the revolution. Just inside the entrance to the exhibit was the “Lenin Wall.” Lots of Lenin, including a small statue. Besides that, the exhibit featured paintings, posters, prints, drawings, photos, magazines, film, agitprop ephemera, porcelain, figurines, life-size reconstructions of early Soviet display objects or spaces commissioned especially for the exhibition, and more.

Besides that, the exhibit featured paintings, posters, prints, drawings, photos, magazines, film, agitprop ephemera, porcelain, figurines, life-size reconstructions of early Soviet display objects or spaces commissioned especially for the exhibition, and more. That’s because I used to have a Suprematist-style cup and saucer. Actually, I still have the saucer, but the cup broke long ago.

That’s because I used to have a Suprematist-style cup and saucer. Actually, I still have the saucer, but the cup broke long ago. That’s a preliminary design for a Mosselprom building advertisement for cooking oil by Aleksandr Rodchenko, the Constructivist.

That’s a preliminary design for a Mosselprom building advertisement for cooking oil by Aleksandr Rodchenko, the Constructivist. And the cover of a magazine called Atheist at the Workbench, Jan. 1923 (Dmitrii Moor).

And the cover of a magazine called Atheist at the Workbench, Jan. 1923 (Dmitrii Moor). The theme of that cover is “We got rid of the tsars on Earth, let’s deal with the ones in Heaven.”

The theme of that cover is “We got rid of the tsars on Earth, let’s deal with the ones in Heaven.” Here’s one of a series of 36 small posters extolling gender equality and increased industrial production (1931). All of them pictured women doing one kind of socialist labor or another, and graphs whose trends were always upward.

Here’s one of a series of 36 small posters extolling gender equality and increased industrial production (1931). All of them pictured women doing one kind of socialist labor or another, and graphs whose trends were always upward. If there had been a collection of postcards in the gift shop based on these posters, at a reasonable price, I would have bought it. Or a Suprematist tea cup. But no.

If there had been a collection of postcards in the gift shop based on these posters, at a reasonable price, I would have bought it. Or a Suprematist tea cup. But no.