A docent at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago, asked me how long it has been since I last visited the museum. I couldn’t remember. I’m pretty sure it was sometime after the current building opened 20 years ago, though I couldn’t say when, or what I saw. Reason enough to visit again on a pleasant September Saturday in 2016.

Encyclopedia Chicago says that “the new building clad in aluminum and Indiana limestone opened in June 1996 in a 24-hour summer solstice celebration. Referencing the modernism of Mies van der Rohe as well as the tradition of Chicago architecture, the $46 million structure is among the largest in the United States devoted to contemporary art. Its 45,000 square feet of galleries, with a permanent collection boasting more than 5,600 works and a 300-seat auditorium and outdoor sculpture garden, is suitable for large-scale artworks, new media, and ever larger audiences.”

Maybe so, but the structure, designed by German architect Josef Paul Kleihues, presents an unfriendly face to the public.

I don’t dislike it, exactly, but it doesn’t say art museum to me. Change the signage just a little and you’ve got a police headquarters, a telecom company, or a top-drawer server farm. Then again, art museums don’t have to look like the Art Institute either. MCA is what it is on the outside, and an interesting museum on the inside.

I don’t dislike it, exactly, but it doesn’t say art museum to me. Change the signage just a little and you’ve got a police headquarters, a telecom company, or a top-drawer server farm. Then again, art museums don’t have to look like the Art Institute either. MCA is what it is on the outside, and an interesting museum on the inside.

The inside is more welcoming. One example: MCA has some of the more comfy chairs — small sofas enclosed by spacious cubical-like structures — of any museum I’ve been to. Toward the end of our visit, if we’d stayed too long in one of these after so much time on foot, we might have fallen asleep.

Currently the big MCA exhibit is of Kerry James Marshall, an artist I was wholly unfamiliar with, in a show called “Mastry.” That just shows how little I pay attention to contemporary art. He’s a living artist, only a few years older than I am, and a resident of Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. A remarkable body of his work is on display.

Currently the big MCA exhibit is of Kerry James Marshall, an artist I was wholly unfamiliar with, in a show called “Mastry.” That just shows how little I pay attention to contemporary art. He’s a living artist, only a few years older than I am, and a resident of Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. A remarkable body of his work is on display.

Of Marshall, Sam Worley wrote in the April edition of Chicago magazine this year, just before the MCA show opened, “At 25, he decided to return to the basics and paint a self-portrait—a classic portrait, almost. Its title alluded to a great literary work: ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self.’ [1980]

“Marshall used egg tempera, a 13th-century favorite. He adopted compositional techniques associated with artists such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael. But, of course, his subject was black. So black that the shade of his skin is deeper than the portrait’s black background, which he fades into, as if invisible. Compared with conventional European portraiture, it’s like a photo negative….

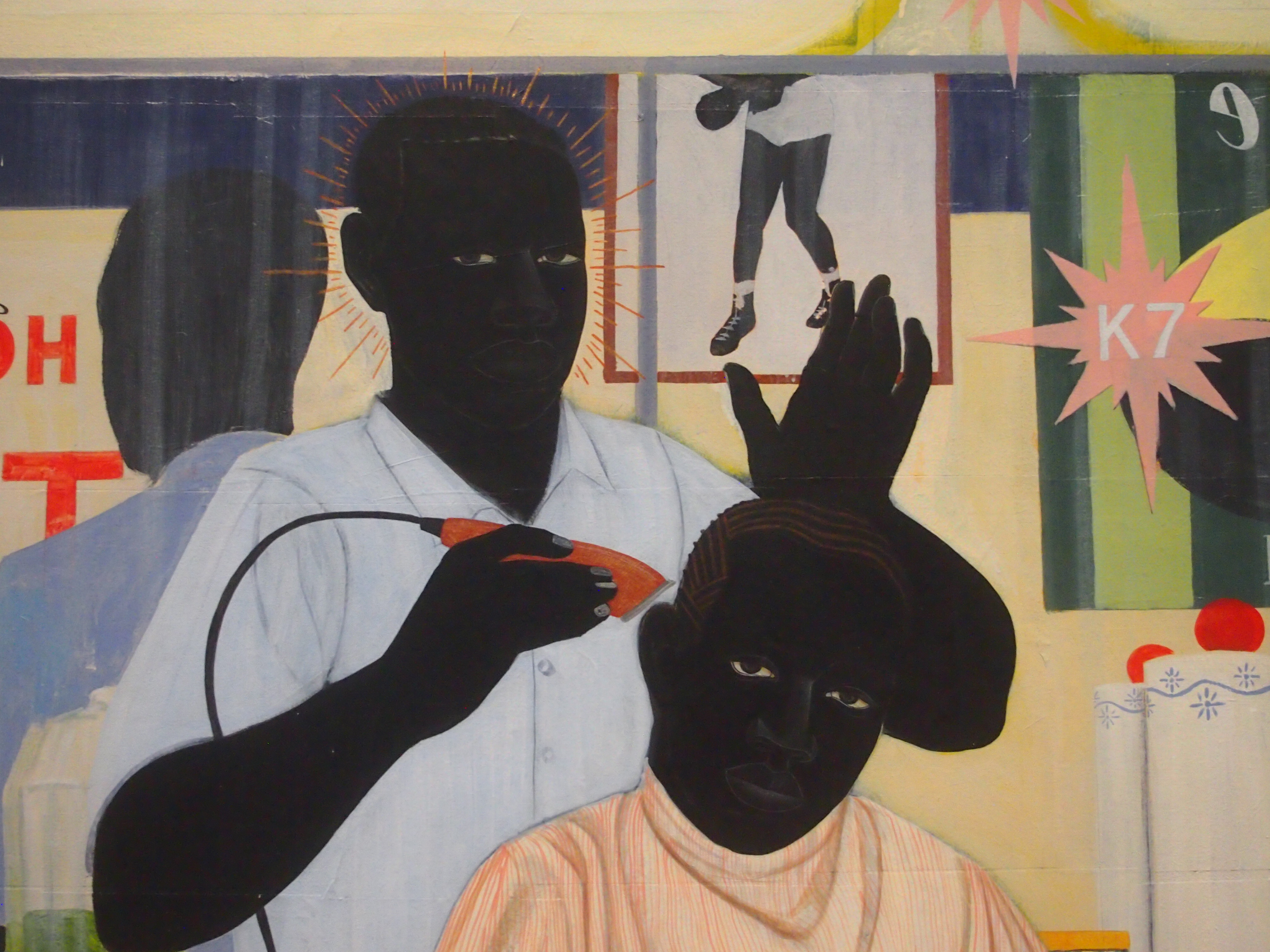

“And so Marshall settled on creating a body of work inspired by and in dialogue with the classics—his early barbershop portrait ‘De Style,’ for example, its name a sly play on the Dutch abstract art movement de Stijl—while remaining resolutely its own thing. He found success with a simple insistence on placing black people, and black history, at the center of his raucous, colorful paintings, and that has opened a space for younger artists.”

A detail from “De Style” (1993).

Here’s one I particularly liked, a more recent painting, “Still Life with Wedding Portrait” (2015).

Here’s one I particularly liked, a more recent painting, “Still Life with Wedding Portrait” (2015).

“In this painting, Marshall imagined a wedding portrait of a young Harriet Tubman… and her first husband, John… presenting her as someone’s beloved wife and not simply the stalwart resistance hero portrayed in standard histories,” the MCA notes.

“In this painting, Marshall imagined a wedding portrait of a young Harriet Tubman… and her first husband, John… presenting her as someone’s beloved wife and not simply the stalwart resistance hero portrayed in standard histories,” the MCA notes.

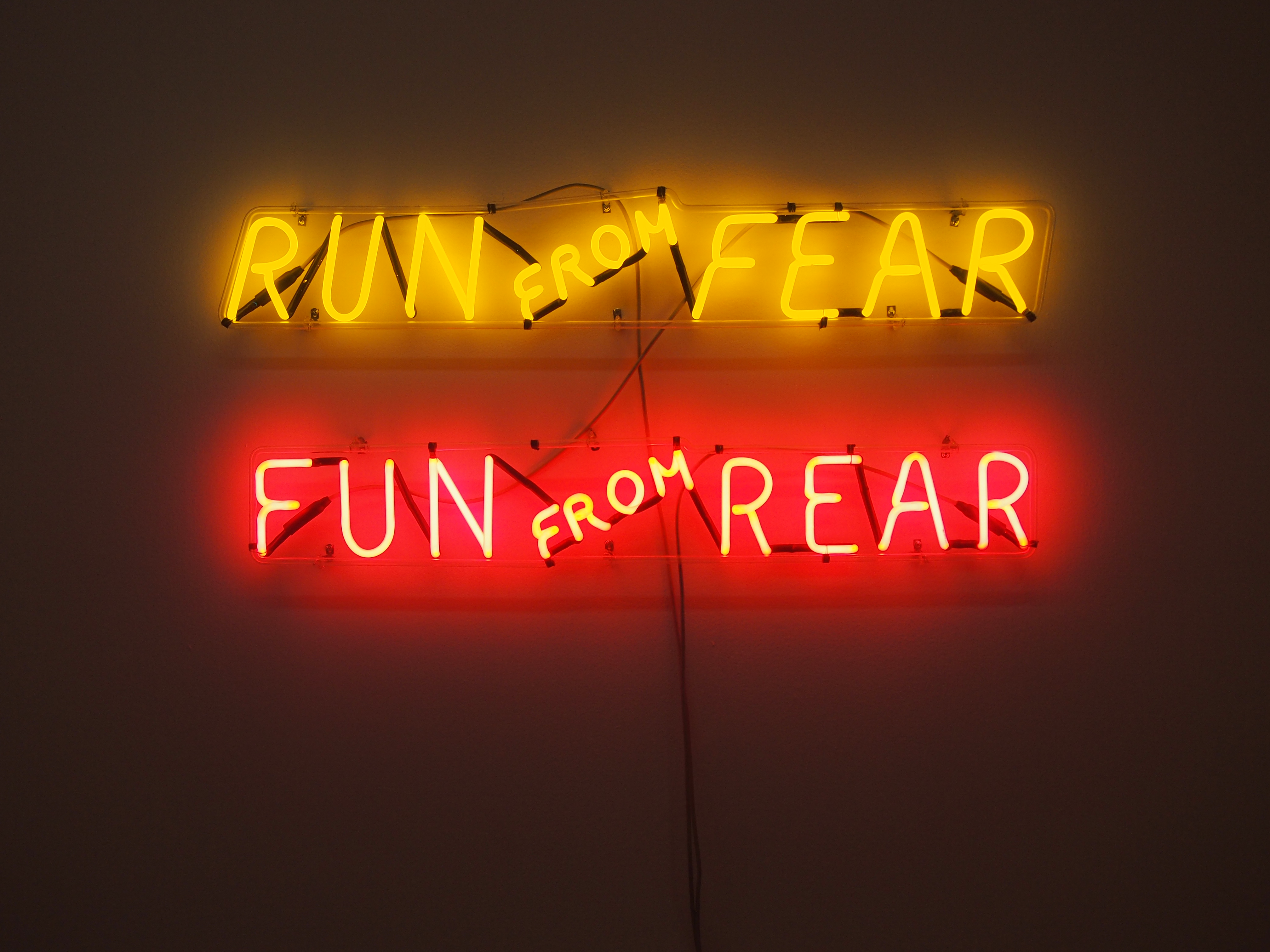

As interesting as the Marshall show was, we also made time for other galleries. I always enjoy a spot of neon.

“Run From Fear, Fun From Rear” (1972) by Bruce Nauman.

“Run From Fear, Fun From Rear” (1972) by Bruce Nauman.

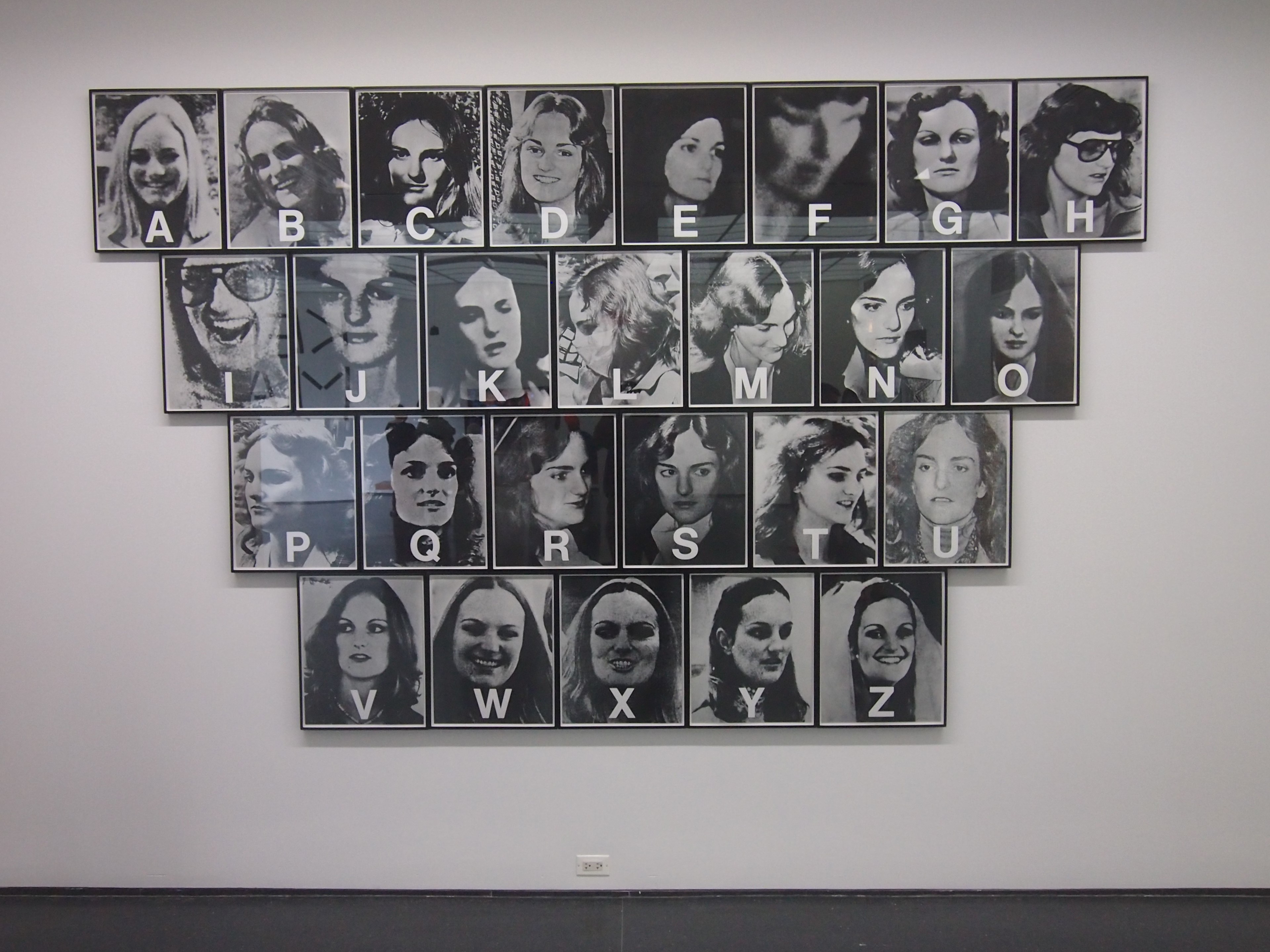

Here are all the portraits of Patty Hearst you could want in one place. Twenty-six, to be exact.

“Patricia Hearst, A thru Z” (1979) by Dennis Adams.

“Patricia Hearst, A thru Z” (1979) by Dennis Adams.

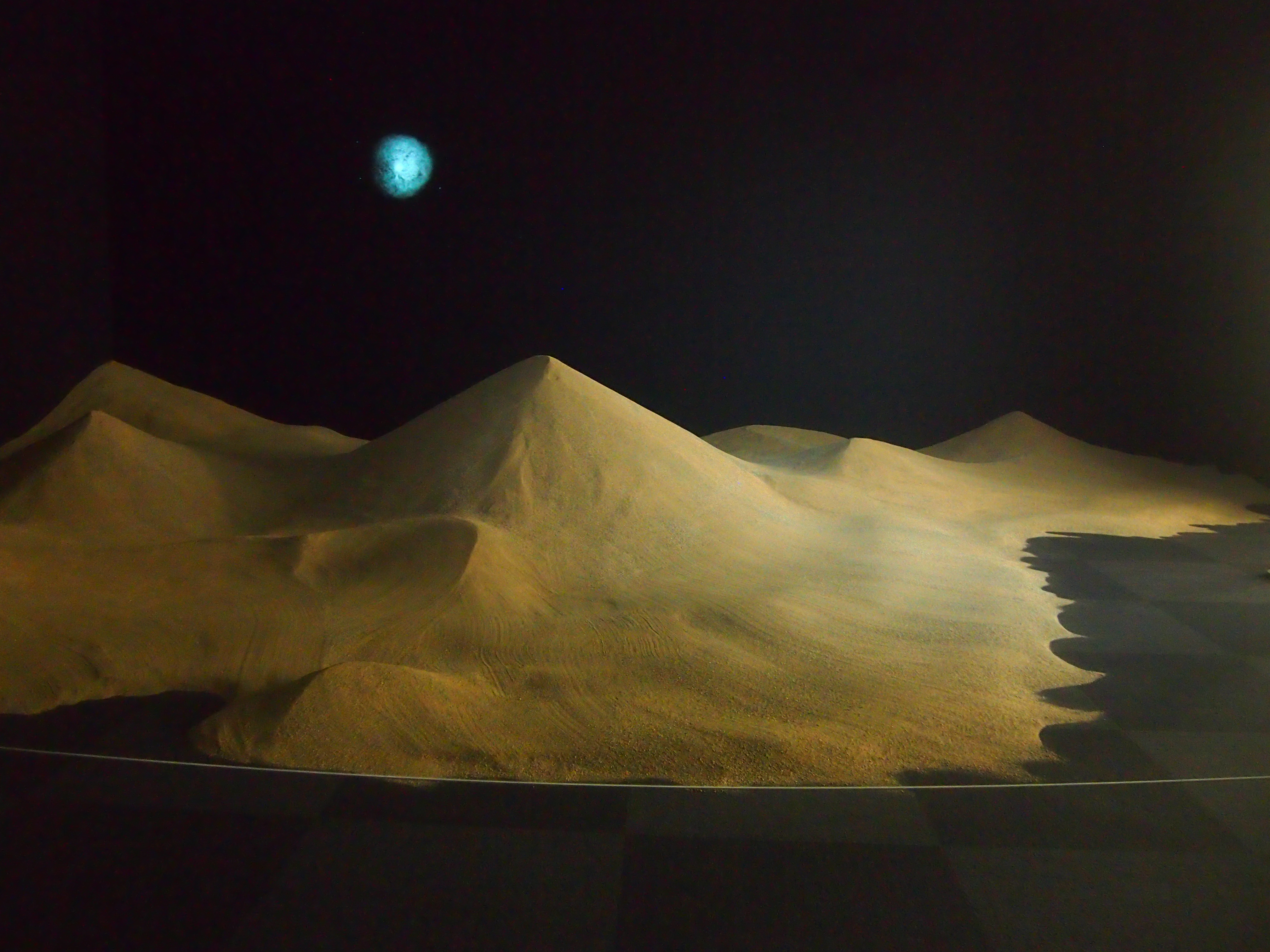

I liked this especially: seven tons of sand on the floor in a dark room, along with radios, LED light box, and some ambient sound.

“A beach (for Carl Sagan)” (2016) by Andrew Yang.

“A beach (for Carl Sagan)” (2016) by Andrew Yang.

MCA says of this: ” ‘The total of stars in the universe is larger than all the grains of sand on all the beaches of planet earth.’ So claimed Carl Sagan. In fact, astronomers estimated in 2003 that for every grain of sand on Earth’s beaches and deserts there exist ten times as many stars above. Yang takes Sagan’s pronouncement to heart in a scale model of the Milky Way in which one grain of sand represents one star; the estimated 100 billion stars are approximated by more than seven tons of sand.”

A scale model in numbers, but not size. How far would you have to scatter the sand to get that? That probably wouldn’t be too hard to figure out, but I don’t feel like it just now. I imagine it would be from here to one of the outer planets in the Solar System.

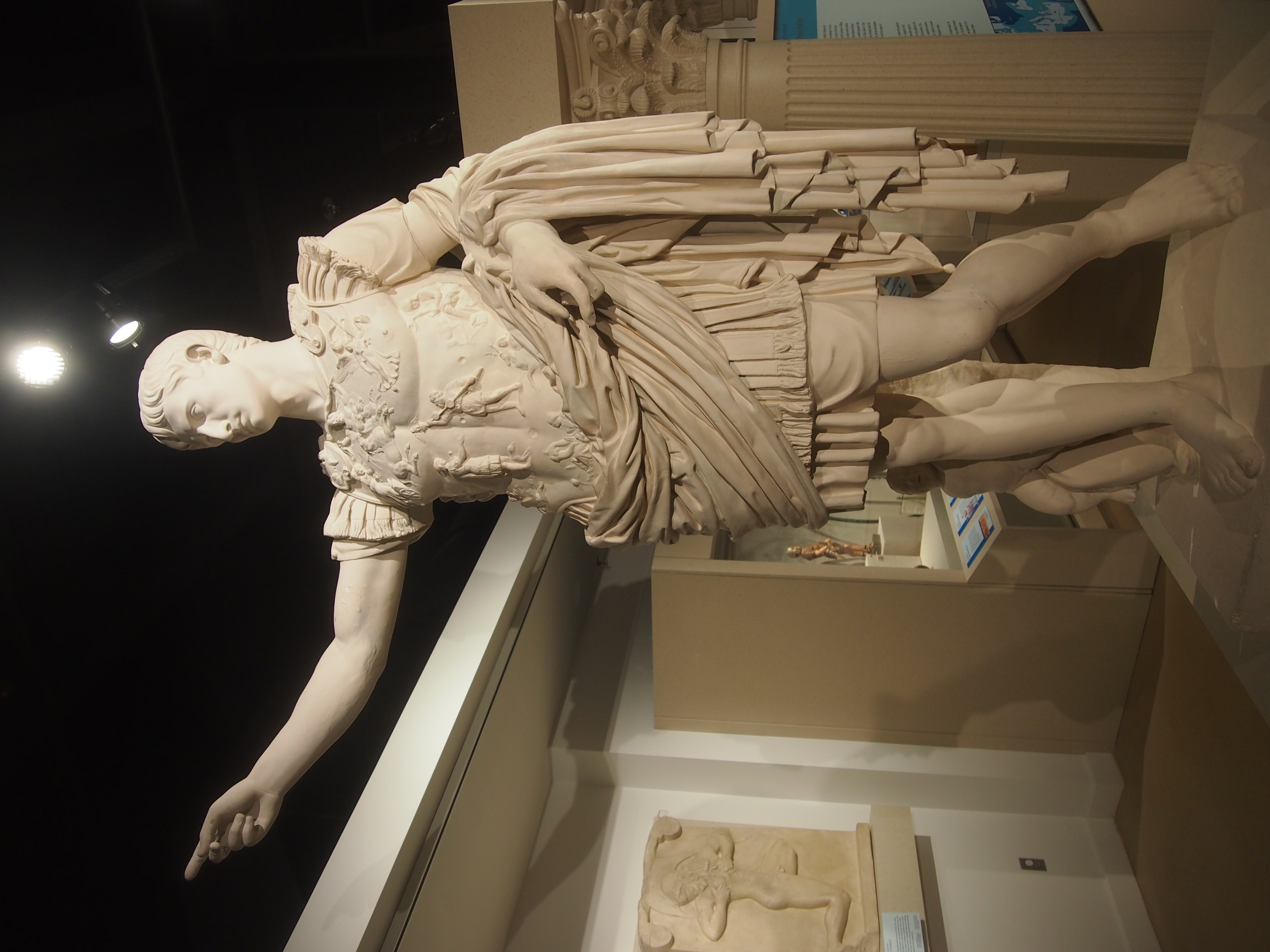

Behind the building, the museum has a sculpture garden. With only four — or was it five? — works. Quantity isn’t everything, but I think there should be more. Here’s “Graz Grosse Geister,” by German artist Thomas Schütte.

At some point during the visit I noticed that the museum guards weren’t just wearing black shirts with GUARD written on the back.

At some point during the visit I noticed that the museum guards weren’t just wearing black shirts with GUARD written on the back.

AVANT was on the front.

AVANT was on the front.

Just a little art joke, no extra charge.

There are a handful of outdoor sculptures on the campus. Here’s one — “The Juggler,” by David J. Foster (2010) — that would be fun to have in the back yard. Except for maintenance costs and all the unwanted attention it would attract, especially at first.

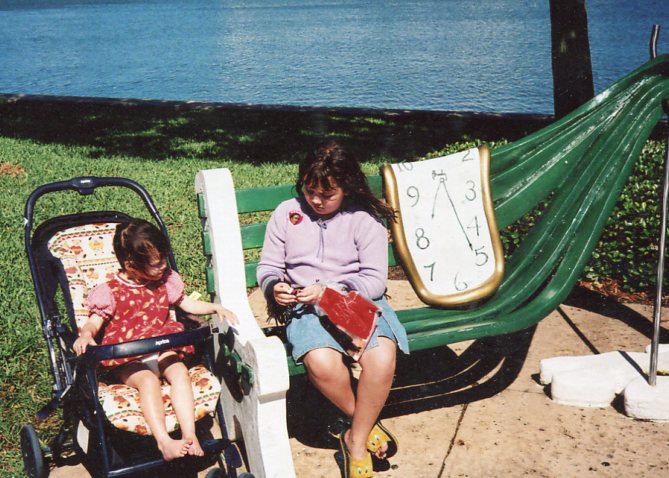

There are a handful of outdoor sculptures on the campus. Here’s one — “The Juggler,” by David J. Foster (2010) — that would be fun to have in the back yard. Except for maintenance costs and all the unwanted attention it would attract, especially at first. The campus, which opened in the early 1990s, includes the Discovery Center Museum, Northern Public Radio, Rockford Art Museum, Rockford Dance Company and some part of the Rockford Symphony Orchestra, though that group performs at the ornate Coronado Theater. I’m pretty sure that the Discovery Center, which is a children’s museum, hasn’t been there that long, but relocated in more recent years. I remember taking the kids there more than 10 years ago, and while I couldn’t say exactly where we went, it wasn’t near the river.

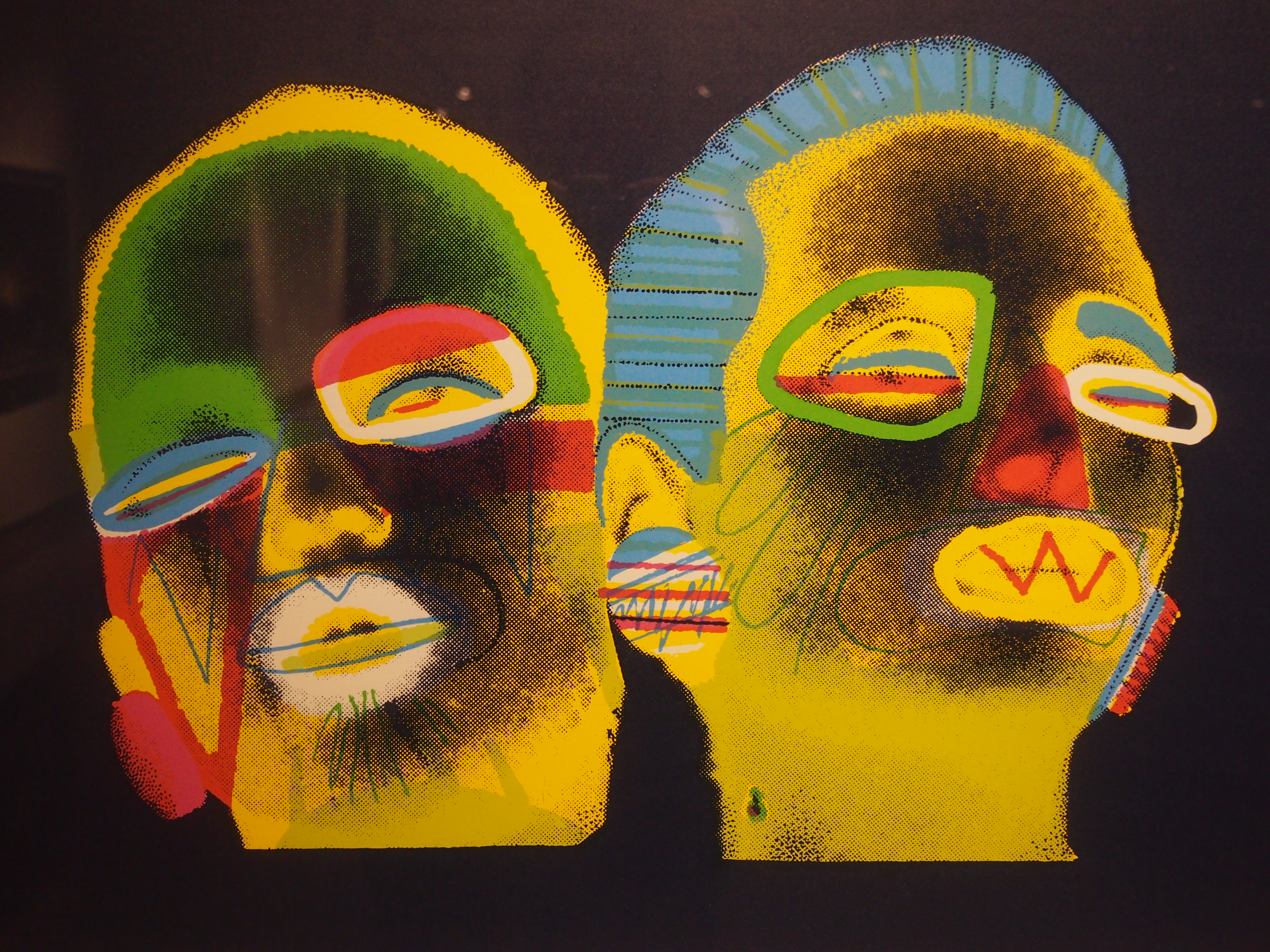

The campus, which opened in the early 1990s, includes the Discovery Center Museum, Northern Public Radio, Rockford Art Museum, Rockford Dance Company and some part of the Rockford Symphony Orchestra, though that group performs at the ornate Coronado Theater. I’m pretty sure that the Discovery Center, which is a children’s museum, hasn’t been there that long, but relocated in more recent years. I remember taking the kids there more than 10 years ago, and while I couldn’t say exactly where we went, it wasn’t near the river. The museum has some interesting items. That’s all I ask of most museums. Here’s a detail of “Indigo Deux” by Ed Paschke (1988).

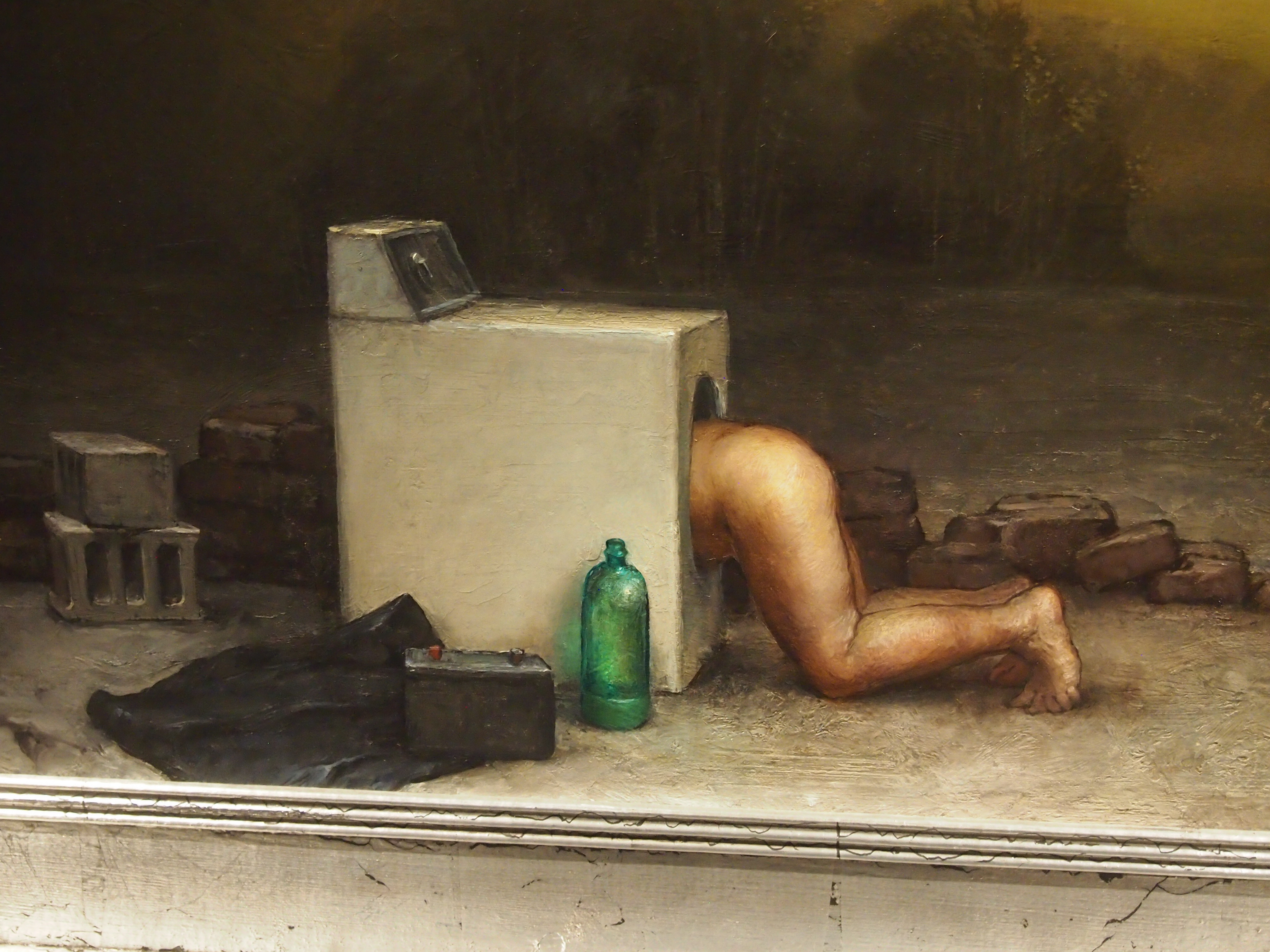

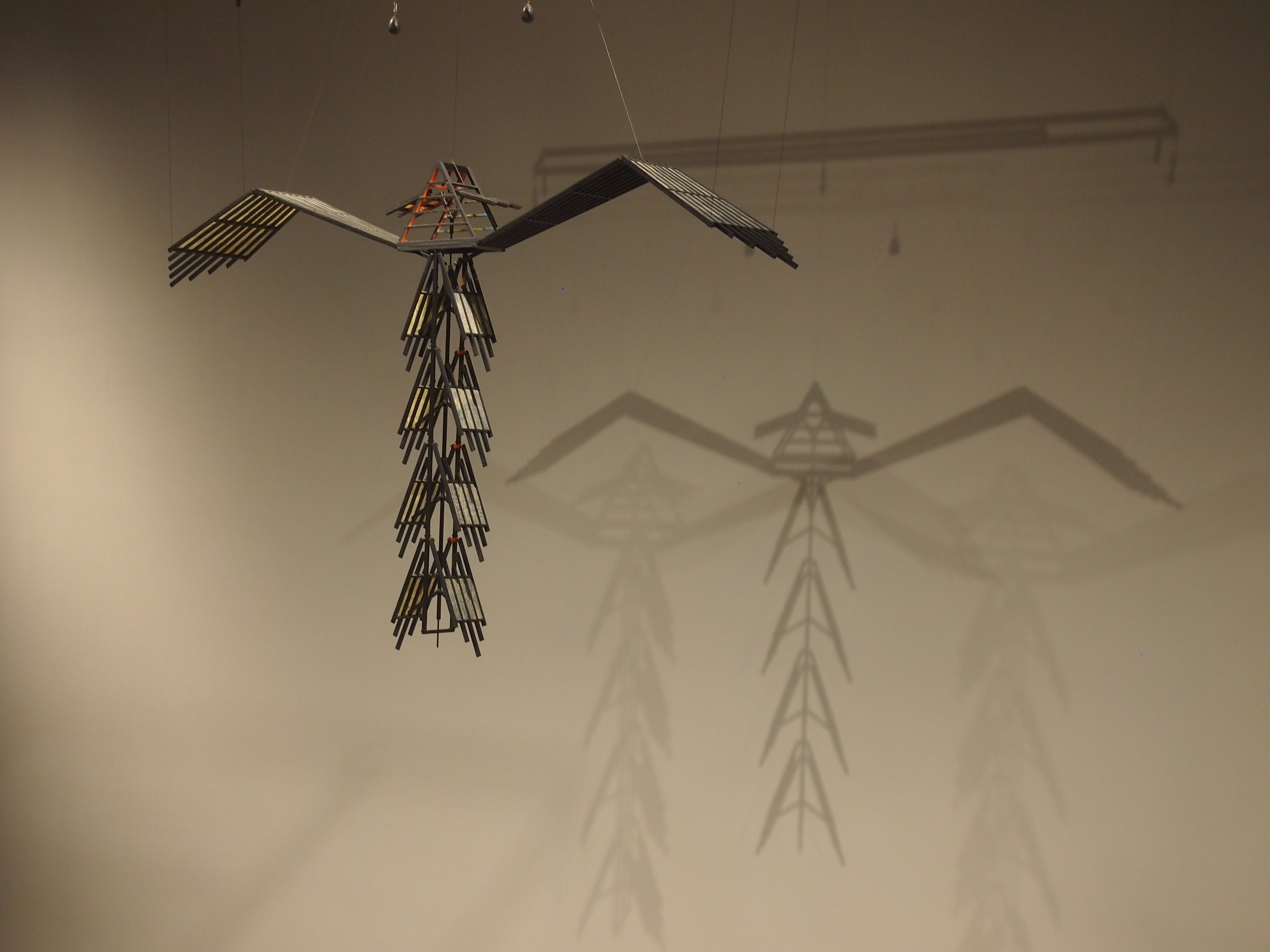

The museum has some interesting items. That’s all I ask of most museums. Here’s a detail of “Indigo Deux” by Ed Paschke (1988). Another detail, this one of “Millennium 16/The Launderer” by Steven Hudson (1993).

Another detail, this one of “Millennium 16/The Launderer” by Steven Hudson (1993). And “Not Knot #18” by Jackie Kazarian (1991).

And “Not Knot #18” by Jackie Kazarian (1991). All in all, a small but good museum. Worth the relatively short drive to Rockford, as are the Nicholas Conservatory, Klehm Arboretum and Anderson Japanese Gardens.

All in all, a small but good museum. Worth the relatively short drive to Rockford, as are the Nicholas Conservatory, Klehm Arboretum and Anderson Japanese Gardens.