By chance today I saw about 10 minutes of Pompeii, a movie that apparently came out last year. The scene pitted gladiators vs. Roman soldiers, and clearly the gladiators were the put-upon salt-of-the-earth hero and his friends, while the soldiers fought for a cartoon Roman upper-class twit bad guy. I watched anyway. Nothing like a little implausible sword play to liven your afternoon. It didn’t take long to come to the conclusion that overall the movie was very stupid indeed.

But maybe I should have watched the end. According to Marc Savlov in the Austin Chronicle: “We all know what happens in the end and, to his credit, Anderson [the director] totally nails the vulcanization of Pompeii. You want it? You got it: flaming chariot melees, massive tsunamis, and a downright hellacious pyroclastic flowgasm that makes the ones in Dante’s Peak look like so many Etch-a-Sketch doodlings (all of it shot in well-above-average 3-D). Pompeii delivers the goods – well, at least during its final 20 minutes.”

It took me a while to remember what EMP stands for in the EMP Museum in Seattle, which I visited on the afternoon of August 28. That evening I said (jokingly) that I’d gone to the Electromagnetic Pulse Museum, because I’d forgotten it stands for Experience Music Project.

The EMP is at Seattle Center, just north of downtown. Seattle Center was the site of the 1962 world’s fair, interestingly known as the Century 21 Exposition. EMP didn’t come along until near the actual beginning of the 21st century, back in 2000, as the creation of Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen and right-angle averse starchitect Frank Gehry.

It’s a colorful 140,000-square foot blob of a building, roundly hated by many. I didn’t hate it, but it didn’t inspire much admiration in me either. I’ve seen plenty uglier buildings, following my own visceral and idiosyncratic standard for ugliness, which is uninformed by theory. Most parking garages are worse. So are many brutalist and otherwise concrete-based structures. EMP just seemed like Gehry being Gehry.

I understand it was a technical marvel to build, with more than 21,000 exterior aluminum and stainless steel shingles all uniquely shaped and designed to fit together like pieces of a puzzle, and an interior defined by strange irregular shapes and held up by 280 steel ribs. I found myself looking up at the interior with more admiration than the exterior. The engineers needed a terrific amount of computing power to design and put the thing together, which somehow seems fitting, considering that a software philanthropist paid for it.

Here’s an odd assertion from the museum: “If [the building’s] 400 tons of structural steel were stretched into the lightest banjo string, it would extend one-fourth of the way to Venus.” That must mean the average distance, since the true distance from the Earth to Venus changes every moment. Or maybe it means the distance between the orbits of Earth and Venus.

Wonder how many ping-pong balls it would take to fill it. Someone at the museum needs to figure that out.

Richard Seven wrote in the Seattle Times in 2010: “A smashed guitar, in honor of Seattle’s Jimi Hendrix and his rebellious style, was the inspiration and template. But the real collision was between one of the world’s most relentlessly anti-box architects, an unfathomable task of trying to freeze the rock ‘n’ roll process, and a wealthy private client who embraced the costs and advances in computing and engineering that allowed a building like that to even stand…

“When he toured the building just before it opened in the summer of 2000, Gehry told reporters, ‘It’s supposed to be unusual. Nobody has seen this before or will see it again. Nobody will build another one.’ ” Probably so.

As a museum, EMP is devoted to pop culture. Though “music” is in the name — and Jimi Hendrix and Nirvana each have their own galleries — that’s only part of the equation. One of the current exhibits, for instance, is “Star Wars and the Power of Costume,” which sounds like a display of costumes from that franchise. It cost extra, so I took a pass.

I didn’t miss “What’s Up Doc? The Animation of Chuck Jones.” That alone was almost worth the inflated price of admission to EMP. Besides original sketches and drawings, storyboards, production backgrounds, animation cels, photographs, and a fair amount to read, there was the opportunity to see cartoons on big screens, such as “What’s Opera, Doc?”, one of the Roadrunner cartoons — I forget which, not that it matters — and “One Froggy Evening,” which I probably hadn’t seen in more than 30 years, and which I didn’t fully appreciate when young. Especially the notion of a frog singing tunes from the 1890s.

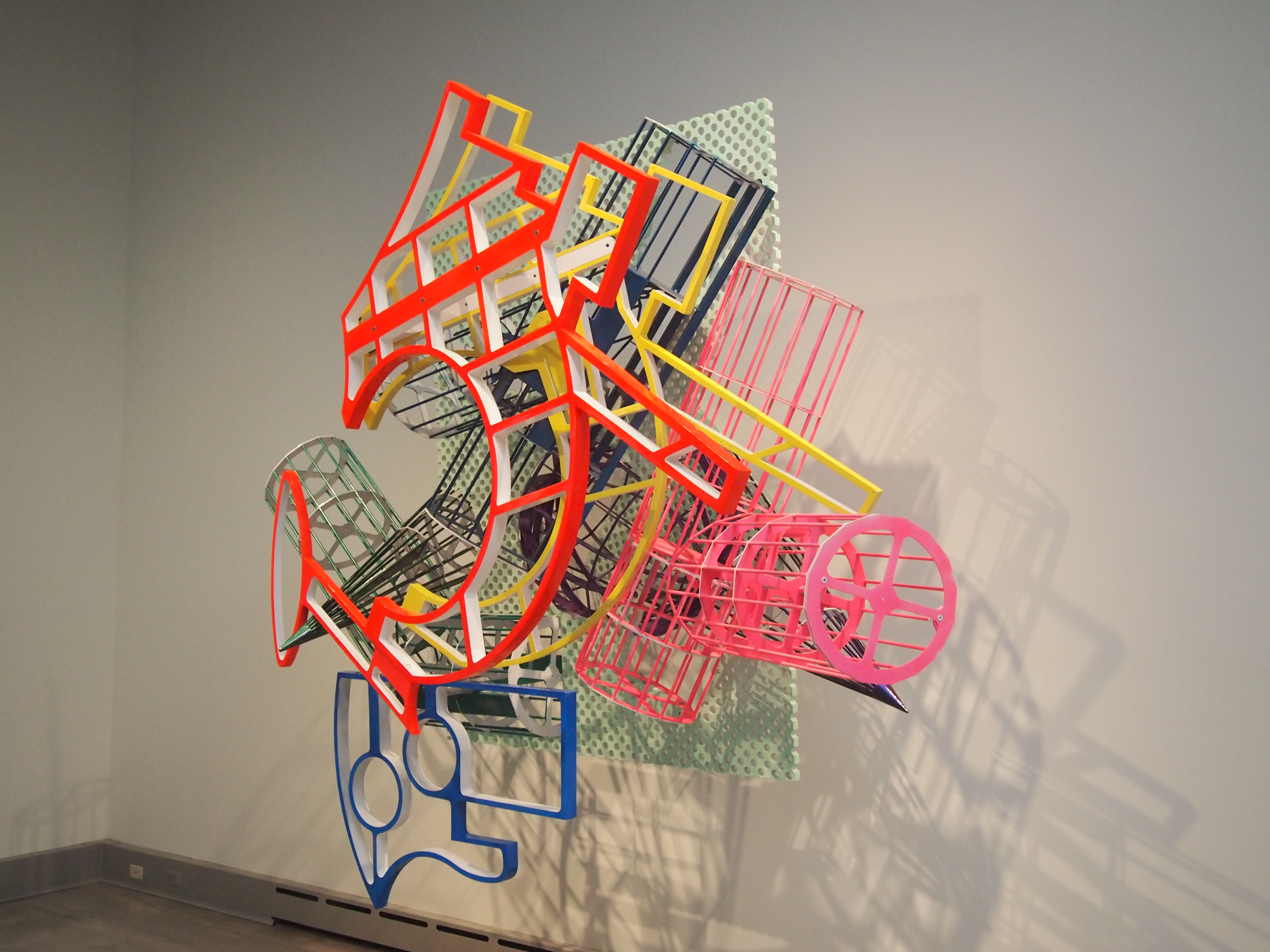

The museum features some impressively large installations. One is made of guitars. A lot of guitars, arrayed upward in a kind of mass cone of guitars (and banjos and keyboards and other musical instruments) two stories high. The work is called “IF VI WAS IX,” and it was put together by a Seattle artist who goes by the single name Trimpin.

It’s more than just a cone of instruments. EMP notes that “short stretches of music were played into a computer then organized by Trimpin into a continuous electronic composition, with notes assigned to specific instruments. Customized robotic guitars play one string at a time. Six guitars work together to create the sound of one chord—a mechanical metaphor for how musical styles and traditions continue to influence one another.”

Nearby is the “Sky Church” room, whose main feature is a 33’ x 60’ HD LED screen that projects images on (from?) an enormous wall. The 65-foot ceiling is illuminated with parasols that seem to float overhead, and the space is well equipped with special-effects lighting. Technically impressive.

The perfect venue for, say, the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon. Or “Steamboat Willie.” Or “Duck Amuck.” Or the “Thriller” music video. Or any of many possibilities. All short, all worth seeing on a vast screen. Maybe shorts like these play at the Sky Church, but the day I was there, the venue seemed mostly to pump out music videos for people under 30.

I’ve read that the full name of the museum used to be the Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame (with the clunky initials EMP|SFM), but some years ago, the science fiction aspect was demoted. The museum still covers science fiction, as well as the horror genre, but in two galleries in the basement.

Not bad displays. I enjoyed seeing an assortment of SF movie and TV show props, such as the original Terminator’s leather jacket and I forget what else (no Lost In Space Robot, though), and playing with at least one of the interactive features: a large globe that would take on the likeness of each of the Solar System’s planets, along with the Moon (and Titan?), at the touch of a button.

Oddly enough, I got more out of the horror exhibit than the SF one. Besides static displays and props and the like, the horror gallery included a number of alcoves in which you can watch well-made short films on various renowned horror movies. These proved interesting, even though I don’t much care one way or the other about the genre.

Because of these shorts, I’m now inspired to watch two horror movies I’ve never gotten around to: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Exorcist. The former was on TCM late Sunday night, but I didn’t want to stay up late to watch it; such is middle age. I did see the haunting green credits, however, and I’ll get around to the whole thing before long.

There’s also a first-floor gallery devoted to the fantasy genre, but by the time I got there, I was a little tired of the museum. At least I happened to see the costume that Mandy Patinkin wore as Inigo Montoya.

As mentioned, two Seattle musical acts, Jimi Hindrix and Nirvana, had their own galleries. Of the two, I spent more time in the Hindrix room, despite being too young when he was alive to fully appreciate his talents, since he was common enough on the radio well into the 1970s. As for Nirvana, I was too old to appreciate them when they were around, and in fact out of the country during their heyday. I remember hearing about Kurt Cobain’s suicide right after I arrived in Hong Kong in April 1994, and my first thought was, Who?

Both galleries apparently change from time to time, rather than being generic tributes to the artists. The Hendrix exhibit I saw was “Wild Blue Angel: Hendrix Abroad, 1966-1970.” It detailed his travels as a successful musician. As the museum explains: “At the height of his fame, Jimi Hendrix performed more than 500 times in 15 countries and recorded 130 songs in 16 studios. He was a musical nomad, his life an endless series of venues, recording sessions, flights, and hotels.”

His passport was on display. I got a kick out of that. Even better, while the original was behind glass, you could leaf through a replica, which I did. The dude got around.

We saw some of time-honored exhibits at the Field, such as Sue the T. Rex. People sure are fond of taking its picture.

We saw some of time-honored exhibits at the Field, such as Sue the T. Rex. People sure are fond of taking its picture. Not very many people were down in the basement looking at the Man-Eater of Mfuwe, but there it was, behind glass.

Not very many people were down in the basement looking at the Man-Eater of Mfuwe, but there it was, behind glass. “This cat terrorized Zambia’s Luangwa River Valley — near Msoro Monty’s [a 1920s man-eater] old stamping grounds — in 1991,” notes the Smithsonian. “After killing at least six people, the lion strutted through the center of a village, reportedly carrying a laundry bag that had belonged to one of his victims. A California man on safari, after waiting in a hunting blind for 20 nights, later shot and killed him.” Unlike Cecil the Lion, there was no international outrage over that.

“This cat terrorized Zambia’s Luangwa River Valley — near Msoro Monty’s [a 1920s man-eater] old stamping grounds — in 1991,” notes the Smithsonian. “After killing at least six people, the lion strutted through the center of a village, reportedly carrying a laundry bag that had belonged to one of his victims. A California man on safari, after waiting in a hunting blind for 20 nights, later shot and killed him.” Unlike Cecil the Lion, there was no international outrage over that. Not quite the selection that the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver has, but impressive. We were among the few in the hall looking at them.

Not quite the selection that the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver has, but impressive. We were among the few in the hall looking at them.