On the last day of July, I stuck up a conversation with a tinsmith. I’d wandered into his shop, a structure he shared with a blacksmith, but the blacksmith wasn’t around, his furnace cool. Tinsmiths don’t need as much heat for their work, so his space was missing a furnace and bellows. The shop was cluttered with tinsmith work, laid out for me or anyone to examine: cups, funnels, pots, candle holders and other items.

“The North West Co. always had tinsmiths working for it,” said the tinsmith, a sandy-bearded and -headed young man in a smock, who went on to share some of his knowledge of tin working with me: the raw tin sheets, actually thin iron sheets with tin coating, the various tools, how the cool shaping was different from shaping hot iron. You only really needed heat for soldering joints, when you’d put an iron soldering rod in a charcoal brazier. This thing he had on hand.

Why made goods here, at a post on the edge of Lake Superior? he asked rhetorically. I guessed the answer before he said it.

“The tinsmiths made trade goods to trade with First Nation peoples for fur pelts,” he said, using a term that is unlikely to have been used 200 years ago.

“Bet they were in high demand,” I said.

“That’s right. Very much so. You know how they heated water before they had tin pots? They’d put heated stones into a leather bag. Tin pots were so much better, but they couldn’t make them themselves.”

Heated stones in leather bags probably hadn’t changed much since the Ojibwa ancestors were new to North America, or more likely well before that.

Then it was my turn to teach the tinsmith something. I asked where the tin came from.

“Cornwall,” he said. “That’s in England, but I’m not quite sure where it is. I’m not too good with geography.”

“You know the peninsula sticking out from the southwest of England? As far southwest as you can go? That’s Cornwall. Devon, then Cornwall, out that way.”

He still looked a little uncertain, but never mind.

“There’s been mining in Cornwall since before the Romans came,” I said. “That’s more than 2,000 years ago. One reason the Romans wanted Britain was for the tin.”

He expressed mild amazement at that.

Not long before our conversation, I’d come to Fort William Historical Park, at the southern edge of modern Thunder Bay, Ontario, where the tinsmith shop and many other buildings stand.

As an open-air museum, Fort William opened a little more than 50 years ago. As an actual North West Co. fur trading post, a major one, its heyday was more than 200 years ago. I understand that the target year the museum is trying to evoke is 1816, not long after the NWC moved here from Grand Portage, and as far as I can tell, it’s spot-on.

The museum and its 42 reconstructed buildings, Ojibwa village and small farm aren’t in the same place as the original. That is several miles (OK, kilometers) away, mostly occupied by a rail yard these days, an interpreter told me. Some, but hardly all of the buildings featured one or more costumed interpreters who were more than happy to talk about their character and his or her times.

The Fort William reconstruction isn’t quite as elaborate as Colonial Williamsburg, but the original settlement wasn’t either, and even so is quite impressive.

Looks empty, but there were a scattering of visitors, along with costumed interpreters, as such the tinsmith, who also happened to be an actual tinsmith. Who better to interpret?

At one moment, another interpreter played his fiddle and yet another one, a woman, led four or five visiting children in a vigorous dance in the main courtyard. Entertainment before electronic gizmos.

Well-stocked interiors, too. Best thing is, you can wander around inside and touch pretty much anything. That’s an advantage of faithful replicas, rather than artifacts.

That last one is the hospital. I also had a chat with the resident early 19th-century doctor, who showed me many horrific medical instruments of the day, such as a bone saw or mechanical leech. Advanced items for such a remote outpost, the doc assured me. Medicines were on hand as well. He discussed several, but the only one I remember now is calamine lotion. Much too expensive to use on itchy bug bites, he said. You just lived with those. Calamine was for serious rashes.

I popped into a large barn-like building to find it stocked with canoes, many hanging from the ceiling, some on the floor, with two interpreters working on building one. A third interpreter, a woman who introduced herself as a member of Ojibwa Fort William First Nation, told me at some length about canoe making as it would have been practiced in 1816. More than I’d ever heard or known before: The raw materials, the sizes and other varieties, how long they lasted (a few seasons), the possible individual markings – figures on the sides.

“This is the most important place in the fort, isn’t it?” I said. She agreed that it was, and the men working on the canoe sounded their approval of the idea (they didn’t talk that much).

You could easily make that case: how could you facilitate pre-modern trade across vast territory connected only by rivers and lakes? No roads, no airplanes, no communication devices. What you had were canoes and muscle power.

More artifacts in more buildings.

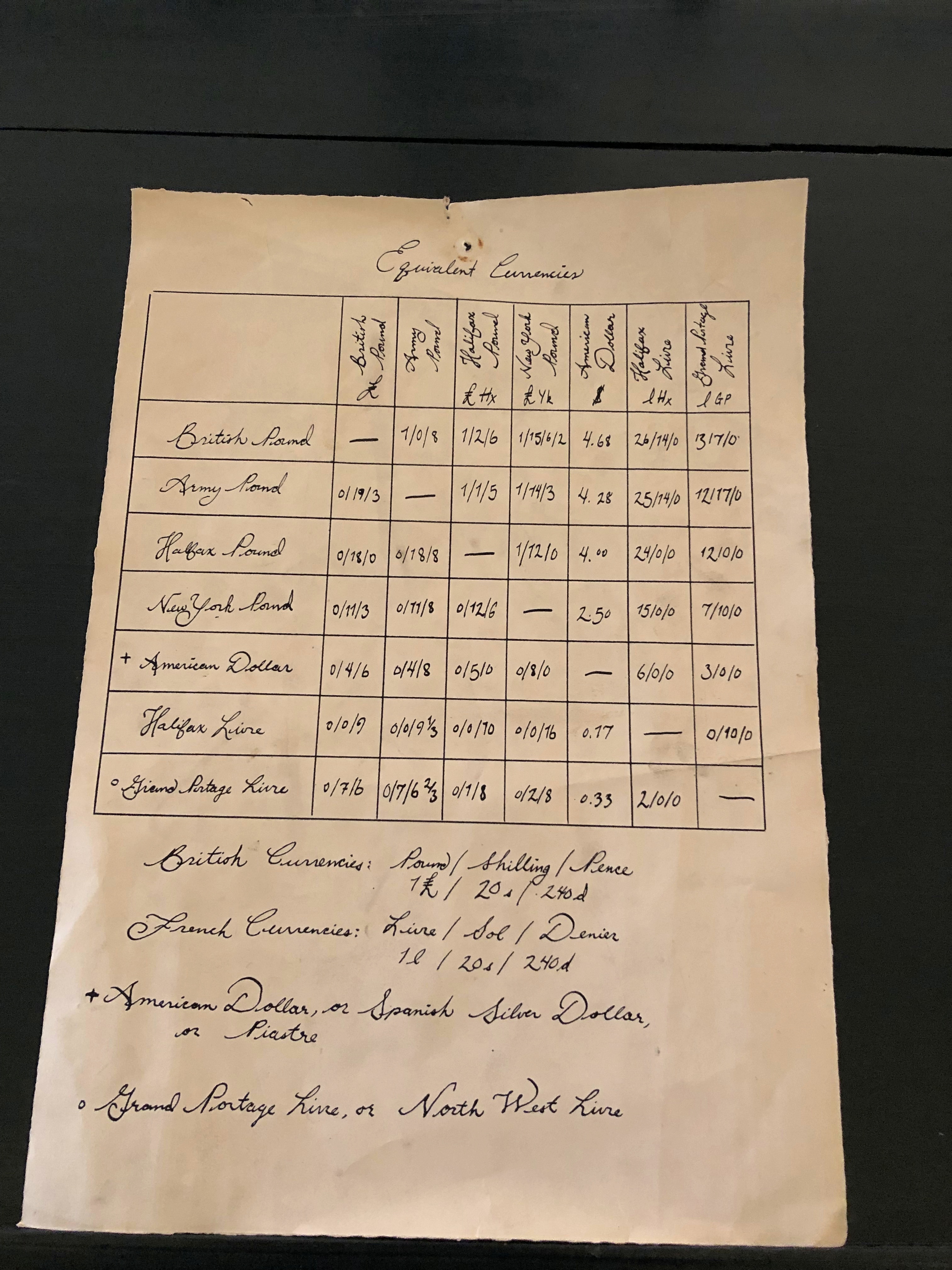

Some obsolete currencies I’d never heard of — the Halifax pound and the Halifax livre, for instance.

The reproduction detail is remarkable all around. I don’t think anyone’s buried here.

But I’m sure the original Fort Williams had a small cemetery, its occupants now lost to time.